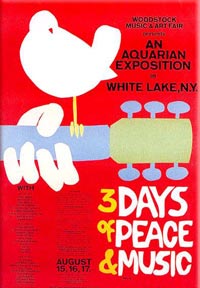

‘Three Days of Peace and Music’ was the promise of the Woodstock Music and Art Festival’s promoters. Four decades on, the effects of the event are still being felt.

‘Three Days of Peace and Music’ was the promise of the Woodstock Music and Art Festival’s promoters. Four decades on, the effects of the event are still being felt.

In August, 1969, just outside Bethel, New York, more than 30 acts performed before an audience in excess of 400,000. Billed as ‘An Aquarian Exhibition,’ it was the moment when the counterculture became the culture. Charles Shultz even named a character in his Peanuts comic strip – a bird – after the festival.

All these years later, Woodstock remains a contentious subject. Was it a stunning testimony to one generation’s breaking away from outmoded values? Or was it evidence of all that was wrong; an unprecedented loosening of morals as sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll ran rampant? There are plenty of advocates on both sides of the issue; but no one can argue that the genie was now out of the bottle.

By 1969, the button-down mindset of the early sixties was well and truly over. The Baby Boomers – the wealthiest and healthiest generation in history – were coming of age. Youth culture pervaded society, and according to the year’s biggest hit single, it was the dawning of the age of Aquarius.

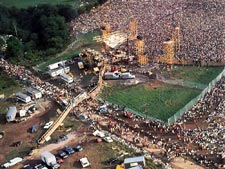

Initial estimates of 60,000 attendees proved way off, as almost half a million showed up – closing the New York State Thruway in the process.

Initial estimates of 60,000 attendees proved way off, as almost half a million showed up – closing the New York State Thruway in the process.

Woodstock was instantly the second largest city in the state. Gates and fences came down, as the crowd grew into the largest single gathering in recorded history. On the second day, officials declared the site a disaster area. Those at ground zero hardly seemed phased.

Wavy Gravy famously announced “Breakfast in bed for 400,000…we’re all feeding each other. We must be in heaven, man! There is always a little bit of heaven in a disaster area.”

When it became clear there was no way to control the influx, promoters decided to make it free festival. In Woodstock, a reporter questions Michael Lang and Artie Kornfeld, wondering why they seem so happy, even though they’ve taken a massive financial hit (it would take 11 years to pay off all festival-associated debts); “Look what you’ve got there, man. You couldn’t buy that for anything,” replies Lang, “These people are communicating with each other. That rarely happens anywhere anymore.”

When it became clear there was no way to control the influx, promoters decided to make it free festival. In Woodstock, a reporter questions Michael Lang and Artie Kornfeld, wondering why they seem so happy, even though they’ve taken a massive financial hit (it would take 11 years to pay off all festival-associated debts); “Look what you’ve got there, man. You couldn’t buy that for anything,” replies Lang, “These people are communicating with each other. That rarely happens anywhere anymore.”

“It has nothing to do with money,” Kornfeld, a successful songwriter with hits by Jan & Dean and the Cowsills to his credit, adds; “It has nothing to do with tangible things. You have to realize the turnabout that I’ve gone through in the last three days… just to really realize what’s really important…The fact that if we can’t all live together and be happy, if you have to be afraid to walk out in the street, if you have to be afraid to smile at somebody, right, well, what kind of a way is that to go through this life?”

The film underscores the divide between generations, as audience members – nearly all under 30 – repeatedly voice objections to their parent’s adherence to tradition mores.

Despite a noticeable lack of police, there were no reported incidents of theft or violence. Lang explains: “This generation, away from the old culture and the older generation…you see how they function on their own. Without cops, without guns…everybody pulls together and everybody helps each other and it works.”

Max Yasgur, the middle-aged dairy farmer on whose 600 acre spread the festival was held, addressed the crowd as an ambassador from the other side: “If the generation gap is to be closed, we older people have to do more than we’ve done.”

The mainstream certainly got the message. Describing festival goers as “pilgrims,” Time Magazine marveled at “the agape-like sharing of food and shelter by total strangers,” and declared “these rock revolutionaries bear a certain resemblance to the early Christians.”

Aside from a few shots of nuns giving the peace sign, any obvious Christian presence was conspicuous in it’s absence, as if the church simply gave up on this reaching this audience.

In spite of the generational and cultural divide, gospel music was heard repeatedly throughout the weekend. Festival opener Richie Havens closed his set with an adaptation of ‘Freedom (Motherless Children),’ which the second act of the day, Sweetwater, then sang to open their portion of the show. Joan Baez included an accapella ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’ before closing with ‘We Shall Overcome,’ and Arlo Guthrie performed ‘Amazing Grace,’ and ‘Oh Mary Don’t You Weep.’

In spite of the generational and cultural divide, gospel music was heard repeatedly throughout the weekend. Festival opener Richie Havens closed his set with an adaptation of ‘Freedom (Motherless Children),’ which the second act of the day, Sweetwater, then sang to open their portion of the show. Joan Baez included an accapella ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’ before closing with ‘We Shall Overcome,’ and Arlo Guthrie performed ‘Amazing Grace,’ and ‘Oh Mary Don’t You Weep.’

Recent material in the same vein was just as popular; the Band and Joe Cocker each covered Bob Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released,’ while both Sweetwater and Joan Baez sang ‘Oh Happy Day’ – a popular hit at that time – and Janis Joplin included two gospel-derived performances in her set: ‘Raise Your Hand’ and ‘Work Me, Lord,’ the latter featuring a plaintive plea to the creator.

In the festival’s opening invocation, Indian guru Swami Satchidananda wholeheartedly endorsed the changes taking place: “America is becoming a whole. America is helping everybody in the material field, but the time has come for America to help the whole world with spirituality, also.”

Drug use is depicted throughout the film, with what – to present day sensibilities – appears an almost willful naiveté regarding any inherent danger. In fact, 40 years ago, the list of high profile casualties was almost non-existent. The following year, three Woodstock headliners would perish in drug-related incidents; but at the time, any risk was seen as minimal.

Which makes it all the more surprising to find an anti-drug presence at the festival, albeit one coming from decidedly left of centre: a Kundalini Yoga instructor leads a class of neophytes, describing the technique as a viable alternative for psychedelic drugs.

Pete Townsend of the Who was among the followers of Indian mystic Meher Baba –who taught that recreational drug use of any kind was damaging, advising that LSD “leads to madness or death.”

Pete Townsend of the Who was among the followers of Indian mystic Meher Baba –who taught that recreational drug use of any kind was damaging, advising that LSD “leads to madness or death.”

“If God can be found through the medium of any drug,” Baba reasoned, “God is not worthy of being God.”

The Who’s rock opera Tommy – which they performed at the festival – was inspired by and dedicated to the guru. Townsend was put off by the entire Woodstock philosophy, and composed ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’ in response to the event.

Never one to mince words, he commented on how “what they thought was an alternative society was basically a field full of six-foot-deep mud laced with LSD. If that was the world they wanted to live in, then f–k the lot of them. “

LSD was an ongoing issue throughout the weekend. Stage announcers warn that the brown acid is simply; “not good,” whereas the blue is out-and-out bad news; “poison – 15 people are sick.” Country Joe advises those who took the green acid: “Go to the hospital tent. I recommend that you don’t take it…wait until you get some stuff that’s good.” Apparently, that would be the Grateful Dead’s stash; the band – all veterans of Ken Kesey’s psychedelic Acid Tests – merrily tossed purple acid into the audience during their set.

LSD was an ongoing issue throughout the weekend. Stage announcers warn that the brown acid is simply; “not good,” whereas the blue is out-and-out bad news; “poison – 15 people are sick.” Country Joe advises those who took the green acid: “Go to the hospital tent. I recommend that you don’t take it…wait until you get some stuff that’s good.” Apparently, that would be the Grateful Dead’s stash; the band – all veterans of Ken Kesey’s psychedelic Acid Tests – merrily tossed purple acid into the audience during their set.

If, as some argue, Woodstock represented the realization of all that was possible, the death of the dream was imminent.

Less than a week before the festival, Charles Manson had masterminded the Tate/LiBianca killing spree in California. It would be months before he was identified as a suspect. At the time, the notion that a member of the hippie community could lead his followers to commit murder – using Beatles songs as motivation – was simply unfathomable.

Four months later, an audience member was brutally murdered by members of the Hell’s Angels during a free concert that the Rolling Stones staged at the Altamont Speedway outside San Francisco. Ironically, the motorcycle club had been hired by the band to provide security.

The following year’s Isle of Wight festival was an even bigger event. Referred to as ‘the last great rock festival,’ the event drew half a million concert goers, but peace and love seemed to be in short supply.

While Joni Mitchell sang the refrain from her ode to Woodstock; “We are stardust/ we are golden/and we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden,” a scuffle broke out onstage, forcing her to stop mid-song. Close to tears – as captured in the film Message To Love – Mitchell pleads with an angry audience for order.

As the years passed, Michael Lang’s optimistic comment; “It’s been working since we got here, and it’s gonna continue working. No matter what happens when they go back to the city, this thing has happened, and it proves that it can happen. That’s what it’s all about,” appeared increasingly out of touch.

Within a decade, the Woodstock generation had turned from Hippie to Yippie to Yuppie, in the process becoming even more materialist than their parents. Disco was the reigning sound, promoting a hedonistic lifestyle that made what had come before seem tame by comparison.

Abbie Hoffman, who coined the phrase ‘Woodstock Nation,’ stayed true to his ideals, but after years of struggling with a bi-polar condition, took his own life in 1989.

In addition to Hendrix, Joplin, and Canned Heat vocalist Al Wilson, Paul Butterfield, Tim Hardin, and various members of the Who, Grateful Dead, Santana, Sha-Na-Na, and the Band all met early deaths as a result of substance abuse.

David Crosby, a fierce social critic famous for railing against the establishment in songs like ‘Almost Cut My Hair’ and ‘Long Time Gone,’ wound up imprisoned in 1982 on drug-related charges, his notoriety as an addict far outstripping his fame as a musician. His excesses would necessitate a liver transplant in 1995. In the book Prisoner of Woodstock, C, S & N drummer Dallas Taylor detailed his own battles with addiction, which ultimately led to liver and kidney transplants.

These days, the majority of performers have long since given up overindulging. Crosby and Taylor both got straight years ago; Taylor now works as an Interventionist, specializing in alcoholism and chemical dependency.

Many of the performers have embraced faith. Typical of festival ethos – variety defines their choices. Sly & the Family Stone guitarist Freddie Stewart is now Pastor Frederick J. Stewart, serving at the Evangelist Temple Fellowship Center in Vallejo, California, while bassist Larry Graham is a long-time Jehovah’s Witness. Following a decades-long heroin habit, Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen embraced Judaism. Arlo Guthrie bought a church in 1991, starting the Guthrie Center, an interdenominational fellowship whose goal is to “find ways to embrace the spiritual journeys of those whose traditions are different, without abandoning our own.”

In it’s wake, the festival spawned an entire industry, including an Oscar-winning documentary film, a best-selling soundtrack album with at least a dozen follow-ups, and a bookshelf worth of writings.

Eventually, interest began to wane. Attempts to repeat the event ended in disaster, and a 25th anniversary box set lasted for a single week at the bottom of the charts before disappearing.

For a variety of reasons – in no small part, interest from an entire generation born long after the event – the 40th anniversary has brought a resurgence of interest. Alongside an expanded reissue of the film, a massive six CD box set and five complete individual performances are being released for the first time. It’s clear there’s an audience eager for more – the initial pressing of the box was sold out within days of it’s release.

Clocking in at just under four hours, the expanded Woodstock: The Director’s Cut offers more of everything. At times, that can be a mixed blessing; director Michael Wadleigh’s use of split screen with varying ratios might have been cutting edge in 1970, but viewing on the home screen can be headache-inducing. Still, it’s a fascinating document.

Clocking in at just under four hours, the expanded Woodstock: The Director’s Cut offers more of everything. At times, that can be a mixed blessing; director Michael Wadleigh’s use of split screen with varying ratios might have been cutting edge in 1970, but viewing on the home screen can be headache-inducing. Still, it’s a fascinating document.

The film opens in the days leading up to the festival, as workers prepare the site. Reactions from townspeople run the gamut; some thrilled to have young visitors, others disgusted by the hordes of hippies.

As almost half a million attendees descend upon green fields, Jerry Garcia notes the almost biblical imagery of what he’s witnessing. Three days later, those same fields, now strewn as far as the eye can see with garbage, offer a fitting harbinger of what was to come in the following decade.

In between, we witness – as Arlo Guthrie called them- a lot of freaks; freaks playing music, freaks listening to music, freaks eating, dealing with a particularly harsh rain shower, and simply digging the vibes.

For all of the press the festival has received – both then and now – too often what gets missed is the very reason the event occurred: the music.

For all of the press the festival has received – both then and now – too often what gets missed is the very reason the event occurred: the music.

Woodstock: 40 Years On: Back to Yasgur’s Farm is far and away the most comprehensive collection yet released. Clocking in at almost eight hours, the massive, six disc box set includes 77 tracks – 38 of which are previously unreleased.

With the exception of The Band, Ten Years After and The Keef Hartley Band, every act is present and accounted for.

For the first time, the music is presented exactly as the audience heard it. The original soundtrack included more than a few doctored performances, and in the case of Arlo Guthrie, Mountain and Crosby Stills, Nash & Young, sourced from entirely separate events. Young’s ‘Sea of Madness,’ for instance, was recorded at the Fillmore East, and one purported live album; Ravi Shankar At the Woodstock Festival, turned out to be a studio recording with applause dubbed in.

For newer acts, the exposure was career-making. Sha Na Na weren’t even signed to a record label when they performed, while Santana and Mountain had yet to release their debut albums. All three quickly moved up to headliners status.

Conversely, Sweetwater, Bert Sommers and Quill played the very same stage, but lost out when they were excluded from the film and soundtrack albums.

Performances omitted from earlier collections are every bit the equal – and sometimes stronger – than what made the first cut. In particular, the Grateful Dead shine on ‘Dark Star.’ Segueing from the Dead at their exploratory best to Creedence Clearwater belting out radio-friendly hits is an exhilarating experience. Blood, Sweat and Tears’ jazz/rock, quirky British folk/rock from the Incredible String Band, and Indian ragas from Ravi Shankar underscore a sense of diversity missing from earlier collections.

Over half an hour of stage announcements – from marriage proposals and birth notices to insulin accessibility and bad acid warnings – reveal a sense of camaraderie that’s hard to imagine today.

Not that it was all peace and love: during the Who’s performance, Abbie Hoffman attempts to halt proceedings with a political diatribe. Pete Townsend – ever the pragmatist – bonks him over the head with his guitar and continues on, leaving Hoffman to nurse his wounds. All these years later, the audio effect is akin to a Tom & Jerry cartoon.

Enhancing the sense of what really went down, a copiously-illustrated 80 page book documents day-by-day events, as well as offering a complete band roster and individual set lists.

Concurrent with the Rhino box, Legacy has issued complete sets from five acts that played the festival. Marketed under the banner ‘The Woodstock Experience,’ each double-disc package includes the artist’s then-current studio release, with Jefferson Airplane (Volunteers), Sly & the Family Stone (Stand), Janis Joplin (I Got Dem ‘Ol Kozmic Blues Again, Mama!), and Santana and Johnny Winter’s self-titled debuts offering ample evidence of the creative frenzy that defined the era.

Concurrent with the Rhino box, Legacy has issued complete sets from five acts that played the festival. Marketed under the banner ‘The Woodstock Experience,’ each double-disc package includes the artist’s then-current studio release, with Jefferson Airplane (Volunteers), Sly & the Family Stone (Stand), Janis Joplin (I Got Dem ‘Ol Kozmic Blues Again, Mama!), and Santana and Johnny Winter’s self-titled debuts offering ample evidence of the creative frenzy that defined the era.

Sly & the Family Stone deliver a set packed with danceable hits and proto-funk workouts. This is Sly at the top of his game, garnering an audience that stretched from AM hit radio to underground FM rock to black soul stations. All the hits are here, including a killer sequence of ‘Dance to the Music’/’Music Lover’/’I Want to Take You Higher.’

Sly’s razor-tight arrangements stand in stark contrast to the Jefferson Airplane’s ragged-but-right approach. Like a precursor to today’s jam bands, songs are deconstructed to the point of barely resembling their more familiar versions, and often stretch to quadruple their original lengths. Two salutes to songwriter Fred Neil (‘The Ballad of You & Me & Pooneil’ and ‘The House at Pooneil Corners’) collectively clock in at almost half an hour, and an extended ‘Wooden Ships’ lasts 21 minutes.

Sly’s razor-tight arrangements stand in stark contrast to the Jefferson Airplane’s ragged-but-right approach. Like a precursor to today’s jam bands, songs are deconstructed to the point of barely resembling their more familiar versions, and often stretch to quadruple their original lengths. Two salutes to songwriter Fred Neil (‘The Ballad of You & Me & Pooneil’ and ‘The House at Pooneil Corners’) collectively clock in at almost half an hour, and an extended ‘Wooden Ships’ lasts 21 minutes.

With Nicky Hopkins sitting in, guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, bassist Jack Casady, and drummer Spencer Dryden take chances at every turn, while Kantner, Grace Slick, and Marty Balin trade vocal lines over top. The group’s roots in folk music – only three years previous – seem like a lifetime ago. At 93 minutes, this is the lengthiest set in the Legacy series, necessitating spreading the performance over the two discs.

The Airplane’s status was such that they were the very first band booked for the festival; their being on the bill legitimized the promoters in the eyes of the other acts.

Of the Legacy releases, Janis Joplin is the only act to deliver a less than stellar performance. It’s not so much her singing, as the lackluster support she’s given. Joplin wanted a Stax Records-style back-up band, and the Kozmic Blues Band, a loose-knit group she put together after leaving Big Brother & the Holding Company the year before, simply don’t deliver. Throughout the set, there’s a sense of disconnect, as they struggle to keep up.

Of the Legacy releases, Janis Joplin is the only act to deliver a less than stellar performance. It’s not so much her singing, as the lackluster support she’s given. Joplin wanted a Stax Records-style back-up band, and the Kozmic Blues Band, a loose-knit group she put together after leaving Big Brother & the Holding Company the year before, simply don’t deliver. Throughout the set, there’s a sense of disconnect, as they struggle to keep up.

Exiting the stage to let her sax player sing ‘Can’t Turn You Loose’ might speak well of her willingness to give others a break, but only serves to highlight how second-rate the band really is.

Making matters worse, the majority of material was unfamiliar to the audience – the Kozmic Blues album wouldn’t come out until a month after Woodstock. Then again, that hardly slowed down Santana or Johnny Winter, both virtual unknowns when they took the stage.

Winters’ debut Columbia LP was only a few weeks old, but he comes across totally assured, playing bottleneck blues and rock with a fire that shows why the label signed him to what was at the time the largest advance ever paid. Despite industry machinations, there’s an absence of hype, as he stretches out on originals and standards by B.B. King, Bo Diddley and Sonny Boy Williamson before closing with his show stopper, ‘Johnny B. Goode.’

Winters’ debut Columbia LP was only a few weeks old, but he comes across totally assured, playing bottleneck blues and rock with a fire that shows why the label signed him to what was at the time the largest advance ever paid. Despite industry machinations, there’s an absence of hype, as he stretches out on originals and standards by B.B. King, Bo Diddley and Sonny Boy Williamson before closing with his show stopper, ‘Johnny B. Goode.’

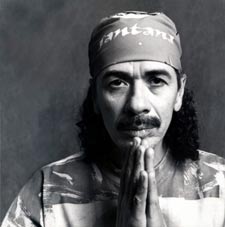

Santana hadn’t even released their debut album when they performed at Woodstock, but by the time they left the stage, they were stars. The film included ‘Soul Sacrifice,’ which featured a memorable solo from drummer Michael Shrieve, who, having just turned 20, was the youngest musician to play the festival. Carlos Santana, the band’s namesake, was only two years older.

As a group, Santana offered one of the first – and still most commercial – tastes of world music. In addition to original material, their set included ‘Jingo’ by Babatunde Olatunji, and ‘Fried Neck Bones and Some Home Fries,’ a Willie Bobo track that never made it onto an official Santana album.

As a group, Santana offered one of the first – and still most commercial – tastes of world music. In addition to original material, their set included ‘Jingo’ by Babatunde Olatunji, and ‘Fried Neck Bones and Some Home Fries,’ a Willie Bobo track that never made it onto an official Santana album.

The idea of mixing rock and blues with Latin and African music was entirely natural, as Shrieve recently explained; “It was that special chemistry of the individual players; a Mexican, a Nicaraguan, a Puerto Rican, a militant black man, and two white boys from the suburbs that made the groove that fit like a glove.”

After a trio of phenomenally successful albums, the signature sound began to change, moving towards jazz fusion starting on 1972’s Caravanserai. As membership begun to fluctuate, Carlos became more and more focused on spiritual issues, becoming a follower of Sri Chinmoy, an Indian spiritual teacher in 1973. Albums like Welcome, Oneness, and Love Devotion Surrender (a duet with fellow Chinmoy devotee Mahavishnu John McLaughlin) put the spiritual above the corporeal.

After a trio of phenomenally successful albums, the signature sound began to change, moving towards jazz fusion starting on 1972’s Caravanserai. As membership begun to fluctuate, Carlos became more and more focused on spiritual issues, becoming a follower of Sri Chinmoy, an Indian spiritual teacher in 1973. Albums like Welcome, Oneness, and Love Devotion Surrender (a duet with fellow Chinmoy devotee Mahavishnu John McLaughlin) put the spiritual above the corporeal.

Despite the intensity of the search, it was never entirely cerebral; the Santana oeuvre is an ongoing mix of the sensual and sacred. While it may not have delivered hit singles, the period offers some of the most intense playing in the band’s catalogue. Lotus, a Japanese triple disc set recorded in 1973, boasts incendiary performances from a truly invigorated band.

Despite the intensity of the search, it was never entirely cerebral; the Santana oeuvre is an ongoing mix of the sensual and sacred. While it may not have delivered hit singles, the period offers some of the most intense playing in the band’s catalogue. Lotus, a Japanese triple disc set recorded in 1973, boasts incendiary performances from a truly invigorated band.

Santana would eventually fall out with Chinmoy over the guru’s anti-homosexual stance, but his spiritual journey continued unabated.

Lyrics were simplistic, but to the point, as in Boroboletta’s ‘Practice What You Preach:’ ‘I know that just being around/it’s easy to go downhill/starting from today/I’ll seek only my Lord’s way.’

‘The River,’ from 1977’s Festival (by which time Santana was the only remaining original member) was written with vocalist Leon Patillo, who sang on three albums before embarking on a career in Christian television ministry.

While he rejects much of traditional Christian theology, Santana’s own lyrics, as in Milagro’s ‘Somewhere In Heaven,’ show an openness to those very same concepts; “He made a promise/Gave every drop of blood/Died on the cross/so we’d be free.”

While he rejects much of traditional Christian theology, Santana’s own lyrics, as in Milagro’s ‘Somewhere In Heaven,’ show an openness to those very same concepts; “He made a promise/Gave every drop of blood/Died on the cross/so we’d be free.”

He claims that even as a child, he understood there are many roads to enlightenment; “My body would not accept the Adam and Eve story or that Jesus is the only thing for everybody. We all are children of Light and we evolved and evolution is a natural state of grace.”

By the 1980s, the band appeared to be a spent force. As sales slowed, Columbia dropped the band from it’s roster. Signing to a new label did little to reverse the slide: 1992’s Milagro has the dubious distinction of being the first Santana album to not even break the Top 100 charts.

After a few more years in the wilderness, 1999’s Supernatural brought about an abrupt change in fortune; the album sold in excess of 25 million copies and earned an unprecedented nine Grammy awards.

Santana maintains the commercial resurgence was foretold by a visit from an archangel named Metatron (“another name for the Holy Spirit or the Christ.”)

The album’s concept – pairing the guitarist with popular vocalists and players like Dave Matthews, Lauryn Hill and Matchbox Twenty singer Rob Thomas (who co-wrote the disc’s most popular track, ‘Smooth’) was designed to sell, and subsequently – outside of guitar solos – employed little of the signature sound.

The album’s concept – pairing the guitarist with popular vocalists and players like Dave Matthews, Lauryn Hill and Matchbox Twenty singer Rob Thomas (who co-wrote the disc’s most popular track, ‘Smooth’) was designed to sell, and subsequently – outside of guitar solos – employed little of the signature sound.

Two subsequent released employing the same formula, but he promises his upcoming album will be truer to his roots; The Son, Father and the Holy Ghost, will be a three-CD set saluting Miles Davis and John Coltrane, along with original material inspired by the masters.

Today, in addition to heading the Milagro Foundation, a children’s charity he founded with his ex-wife, Santana has a number of flourishing business ventures; a line of women’s shoes with over $100 million in sales, a signature brand of popular wine, and partnership in a chain of Mexican restaurants.

His current philosophy shares much with Norman Vincent Peal, who popularized the concept of the power of positive thinking in the 1950s. He’s created Architects of a New Dawn, a website that promises: “To inspire, uplift, engage, and transform the global community through music and positive media content.”

He recently announced plans to retire from music in five years, after which he will establish a church in Maui, which he will pastor. In a Rolling Stone interview he explained “I find that God gave me the gift of communication…the ability to get people unstuck with certain sections of the Bible that have to do with guilt, shame, judgment and fear. The God of that stuff is retarded, demented and not real. The real God is beauty, grace, dignity and unconditional love.”

© John Cody 2009