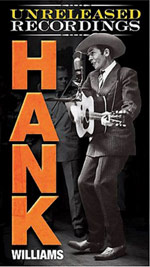

Hank Williams, The Unreleased Recordings, Time/Life

Hank Williams is one of a handful of American artists who changed the way we listen to music.

The single most important figure in the history of country music, his songs – including ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,’ Hey Good Lookin,’ ‘Cold, Cold Heart,’ ‘Mind Your Own Business,’ and ‘I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still In Love With You)’ – are perfect; deceptively simple and to the point, yet offering insights the listener can readily identify with.

Almost single-handedly, Williams changed the perception of country as hillbilly hokum. “It ain’t funny,” he once commented, adding: “folk songs [his preferred term] express the dreams and prayers and hopes of the working people.”

Almost single-handedly, Williams changed the perception of country as hillbilly hokum. “It ain’t funny,” he once commented, adding: “folk songs [his preferred term] express the dreams and prayers and hopes of the working people.”

From the very beginning, Williams, who was born in 1923, faced almost insurmountable struggles in his personal life.

He was afflicted with spina bifida, a congenital defect resulting in an improperly formed spinal cord. The condition was exacerbated by regular beatings at the hands of a domineering mother. A fall from a horse when he was 17 worsened an already bad situation, and numerous surgeries proved unsuccessful. Painkillers became an effective, if short term solution.

His father, institutionalized for alcohol and mental problems, was rarely in the picture; and his only sister ended up in prison. This considerable physical and emotional pain helps explain Williams’ drinking habit, which he developed at 11 years old.

With few practical skills, his prospects were negligible. Had he not possessed such a singular talent, a future similar to his sister’s was probable.

His marriage to the notorious Miss Audrey continued the pattern of physical abuse. Hank clearly suffered at his wife’s hand; but this time he responded in kind, with knock-down fights and chronic unfaithfulness practised by both parties.

Miss Audrey’s insistence – despite a spectacular lack of talent – on performing on-stage with Hank was yet another, albeit more public facet of their dysfunctional relationship.

The couple divorced after three years together, but quickly reconciled. Their only son, Hank Jr. was born in 1949.

By 1951, the grind of constant touring was taking a heavy toll. As a member of the Grand Ole Opry, mandatory weekend performances meant returning to Nashville no matter how far he had traveled during the week.

In January, he took on hosting Mother’s Best Flour Show, a 15-minute weekday radio broadcast. Now, in addition to squeezing in regular recording sessions, he had to pre-record shows for the days he was out of town.

In January, he took on hosting Mother’s Best Flour Show, a 15-minute weekday radio broadcast. Now, in addition to squeezing in regular recording sessions, he had to pre-record shows for the days he was out of town.

His audience grew bigger still after ‘Cold, Cold, Heart’ was released in March. The song became an instant classic as mainstream acts recorded competing cover versions. Five – including Hank’s – placed in the top 30 pop charts that year, with Tony Bennett taking it all the way to #1.

The ongoing pressure was intense. In spite of his reputation for drinking, Williams had managed to spend longer periods of time sober; but when he fell off the wagon, he fell hard. Between attempts to dry out, and back problems, he was hospitalized four times that year.

In December – the very same week ‘Cold, Cold Heart’ was named the most popular country song of the year – Hank’s marriage to Miss Audrey finally came to an end. Incapacitated and unable to perform due to recent back surgery, he was – to quote one of his song titles – alone and forsaken. Singer Johnnie Wright dropped by to check up on his friend, and found a smashed guitar and bullet holes in the screen door.

In December – the very same week ‘Cold, Cold Heart’ was named the most popular country song of the year – Hank’s marriage to Miss Audrey finally came to an end. Incapacitated and unable to perform due to recent back surgery, he was – to quote one of his song titles – alone and forsaken. Singer Johnnie Wright dropped by to check up on his friend, and found a smashed guitar and bullet holes in the screen door.

The total studio output released under Williams’ own name is a mere 66 songs. Considering this, the material collected from Mother’s Best Flour which comprises The Unreleased Recordings is of monumental importance to his legacy. Unheard since their original broadcasts, the three disc set contains 54 performances – including 30 songs he never recorded in any other form.

Hymns and gospel material dominate – almost half of the selections are sacred.

That’s hardly a surprise. Growing up, Williams learned to sing while attending countless gospel meetings, and those experiences informed all that came after.

From start to finish, gospel was a large part of his repertoire. Three of the four selections on his debut recording sessions were spirituals, and ‘Are You Walkin’ And A Talkin’ For the Lord’ would be the final song he ever recorded. His last-ever concert, only days before his passing, included a number of gospel tunes.

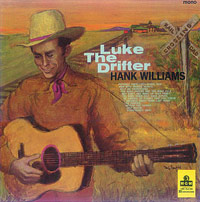

In addition to his own recordings, Williams also recorded as Luke the Drifter. Like a latter-day Will Rogers, Luke mixed age-old truths with humor, offering moralistic tales stressing honesty, integrity and love of God.

In addition to his own recordings, Williams also recorded as Luke the Drifter. Like a latter-day Will Rogers, Luke mixed age-old truths with humor, offering moralistic tales stressing honesty, integrity and love of God.

“You have no right to be the judge, to criticize and condemn,” Luke reasoned in ‘Men with Broken Hearts,’ adding: “Just think, but for the grace of God, it would be you instead of him.”

His sister once commented, “If you want to know Hank, check Luke.”

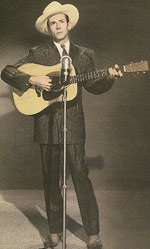

Williams’ charismatic stage persona was invariably good-natured; but many of the performances on The Unreleased Recordings hint at a profound sadness under the happy veneer.

Ongoing marital woes certainly took a toll, but there’s more – a yearning that transcends the temporal. An added sense of foreboding is never more apparent than on the macabre final track, ‘The Pale Horse and His Rider,’ during which he explains “the Bible speaks of a pale horse, and his rider is death.” At the time, Williams was less than two years from his own death.

Toby Marshall almost certainly hastened the inevitable. Always sickly, Hank was experiencing heart problems by the time he met Marshall, a con-man doctor who, much like Elvis Presley’s notorious Dr. Nick, freely prescribed whatever his patients requested.

When he died on Jan 1st, 1953, Williams’ body was wracked with a deadly combination of morphine, chloral hydrate, and alcohol; the autopsy also found he had been severely beaten shortly before his death.

Marshall was unmasked three months later, after his wife died under equally mysterious circumstances. An investigation revealed the so-called doctor lacked any formal medical training, and had a long history of convictions.

Marshall was unmasked three months later, after his wife died under equally mysterious circumstances. An investigation revealed the so-called doctor lacked any formal medical training, and had a long history of convictions.

1952 did bring a far more encouraging relationship for Williams, when, during a hospital stay to dry out, he met Father Harold Purcell. Detecting none of the arrogance he had expected, Purcell instead found Hank to be inquisitive and knowledgeable regarding scripture. The two became fast friends, talking and praying together whenever the opportunity presented itself.

Hank became actively involved in Purcell’s work with children, donating the entire proceeds from a tour towards the construction of a Children’s Hospital, and anonymously contributing sizable monthly gifts to his ministry.

Sadly, the relationship was cut short by Purcell’s premature death shortly before Williams’ own passing.

Sadly, the relationship was cut short by Purcell’s premature death shortly before Williams’ own passing.

As beneficiary, Hank’s mother Lily ultimately received far more from his royalties than he had seen during his lifetime.

Relegated to a back seat during his son’s life, Lonnie Williams was forced to take that position literally at the funeral. Lily, alongside Miss Audrey and Hank’s second wife Billie Jean, sat prominently in the front row, while Lonnie was positioned thirty rows behind.

The three women would subsequently end up in bitter court battles, fighting each other for the estate. The ex-wives – each billed as ‘Mrs. Hank Williams’ – toured the country independently, singing Hank’s songs to ever decreasing audiences.

Literally thousands of artists, from Elvis – Presley and Costello – to James Brown, Louis Armstrong, the Grateful Dead and Norah Jones have gone on to include Williams’ songs in their repertoires.

Literally thousands of artists, from Elvis – Presley and Costello – to James Brown, Louis Armstrong, the Grateful Dead and Norah Jones have gone on to include Williams’ songs in their repertoires.

These days, he would never pass muster in Nashville’s overly contrived, pitch-corrected marketplace. His nasal, southern-to-the-core delivery – pronouncing ‘care’ ‘kee-air,’ and ‘can’t’ as ‘cain’t’ – may have lacked in technique; but it offered an authenticity and sincerity that will never be duplicated.

It would be a stretch to suggest those songs are revelations from God; but they could certainly be considered revelation from man. Hank told interviewers that, for inspiration, he would simply close his mind and let God write the songs.

Awareness of right and wrong is present throughout his work. When he was bad, he knew he was bad, and never made excuses. By all accounts he was a mess of contradictions; but one cannot discount his upbringing. Out of a pained life, Williams’ story is remarkable – and would have been that much sadder without music.

More than half a century after his passing, his music continues to bring joy to listeners everywhere.

© John Cody 2009