The notion of rock music as a bono-fide art form first came about during the mid-to-late sixties. After a decade of being treated as little more than pop fodder, suddenly musicians were deemed every bit the equal of the writers that had shaped western social mores in the first half of the century.

The notion of rock music as a bono-fide art form first came about during the mid-to-late sixties. After a decade of being treated as little more than pop fodder, suddenly musicians were deemed every bit the equal of the writers that had shaped western social mores in the first half of the century.

A recent spate of reissues and previously unreleased vintage material from Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen offers proof that, while not every kid who picked up a guitar created lasting art, the change in perception was warranted.

Few catalogues can rival Dylan’s remarkable series of LPs released in the 1960s.The Beatles and Rolling Stones come closest, but they were collective efforts; you’d have to go back to Elvis to find a single individual who shook things up to a comparable extent.

The Original Mono Recordings spans eight albums over seven years, from his self-titled debut in 1962 through to John Wesley Harding, released in late ’67, shortly before stereo supplanted mono as the de facto format.

The Original Mono Recordings spans eight albums over seven years, from his self-titled debut in 1962 through to John Wesley Harding, released in late ’67, shortly before stereo supplanted mono as the de facto format.

Mono was the format in which the public first heard these records; both on radio and vinyl. For one, it was cheaper – stereo LPs cost a dollar more. Stereo mixes were for the most part afterthought, usually rushed off after proper care had been taken on the more important monaural mixes.

Invariably, there’s a heightened, an almost in-your-face directness, whether on the early material – the notion of guitar, harmonica and voice needing more than a single speaker seems contradictory; a surround sound version of one man – but it continues through onto the electric material.

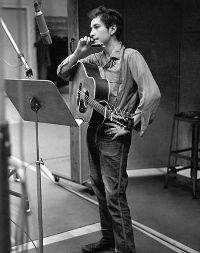

The rapid evolution from Woody Guthrie-inspired folkie, through bohemian beat poet, to rocker and then back to the basics – all in well under a decade – was, and remains, unprecedented. Dylan was constantly on the move, abandoning whatever movement tried to make him their own.

When he plugged in, it was a cataclysmic, life-changing event for many fans. His electric set at the Newport Folk Festival in the summer of ‘65 provoked reactions reminiscent of Stravinsky’s debut of Rite of Spring in a Paris theatre in 1913. Listeners were forced to take sides; Pete Seeger tried to cut the power lines with an axe, while at a concert in England soon after, an outraged audience member, feeling betrayed, famously shouted ‘Judas!’

More than 45 years on, the performances – acoustic and electric – easily transcend their era. Memorable lines tumble out; ‘To live outside the law one must be honest,’ ‘Don’t criticize what you can’t understand,’ ‘He not busy being born is busy dying.’ This was not your mother’s pop music.

While it wasn’t until the following decade that Dylan announced – very publically – that he had become a Bible-believing Christian, it’s easy to spot the thread that leads there.

Poet Allen Ginsberg, after initially ignoring him, claimed of Dylan’s talent; “It’s sort of a Biblical prophecy.” Mavis Staples noted, “They were inspirational songs. And they would inspire. It’s the same a gospel; he was writing truth.”

His longtime producer Bob Johnston put it more bluntly; “I don’t think Dylan had a lot to do with it. I think God instead of touching him on the shoulder, he kicked him in the ass; really. And that’s where all that came from…I mean, he’s got the Holy Spirit about him. You can look at him and tell that.”

His longtime producer Bob Johnston put it more bluntly; “I don’t think Dylan had a lot to do with it. I think God instead of touching him on the shoulder, he kicked him in the ass; really. And that’s where all that came from…I mean, he’s got the Holy Spirit about him. You can look at him and tell that.”

Dylan spent the bulk of his career an intensely private person. That’s all changed; these days, in addition to hosting a well-received radio show, he’s published the first volume of his autobiography, and opened up on his personal life in the film No Direction Home. Ironically, in removing the mystery, he’s simply confirmed the genius.

One of the most fascinating chapters in Dylan’s lengthy career is the 1975-6 Rolling Thunder Revue. Sid Griffith’s Shelter From the Storm offers an in-depth account of the era, which featured a rag-tag group of fellow travelers crisscrossing the country on an old bus, stopping along the way to play once-in-a-lifetime shows.

One of the most fascinating chapters in Dylan’s lengthy career is the 1975-6 Rolling Thunder Revue. Sid Griffith’s Shelter From the Storm offers an in-depth account of the era, which featured a rag-tag group of fellow travelers crisscrossing the country on an old bus, stopping along the way to play once-in-a-lifetime shows.

The talent on board was considerable; Joan Baez, Allen Ginsberg, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Joni Mitchell, Roger McGuinn and more. A number of careers were launched during the tour, including T Bone Burnett, Steven Soles and David Mansfield, who formed the Alpha Band immediately after.

In addition to the live shows, Dylan cast many of the players in his first foray into moviemaking, the four hour plus Renaldo And Clara. Still one of his most misunderstood efforts, Griffith manages to place the film in context, making it fresh for reevaluation.

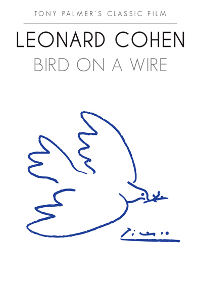

Leonard Cohen came to music already established as a successful poet and writer. His debut LP, 1967’s Songs of Leonard Cohen was met with critical raves and placed him into the upper echelons of the music scene almost overnight. Bird on A Wire offers an close-up view of the man on tour, five years into his career as a performer.

Leonard Cohen came to music already established as a successful poet and writer. His debut LP, 1967’s Songs of Leonard Cohen was met with critical raves and placed him into the upper echelons of the music scene almost overnight. Bird on A Wire offers an close-up view of the man on tour, five years into his career as a performer.

The bond between artist and audience – and how profoundly each affects the other – has rarely been so clearly displayed. Director Tony Palmer (All You Need Is Love) followed Cohen on a 20-city tour across Europe in the spring of 1972. He was only three albums into his recording career at the time, but all three – Songs of Leonard Cohen, Songs From A Room and Songs Of Love and Hate are classics.

The latter, and then most recent, was arguably even more emotionally raw than what had come before. That’s reflected throughout the film. A tangible sense of vulnerability comes across repeatedly onstage and off. Whether dealing with security personnel attacking audience members, or a faulty sound system wreaking havoc, there’s an underlying sense of tension. In the latter case, audience members demand refunds, and as tempers boil over, Cohen offers up his own pocket cash.

The latter, and then most recent, was arguably even more emotionally raw than what had come before. That’s reflected throughout the film. A tangible sense of vulnerability comes across repeatedly onstage and off. Whether dealing with security personnel attacking audience members, or a faulty sound system wreaking havoc, there’s an underlying sense of tension. In the latter case, audience members demand refunds, and as tempers boil over, Cohen offers up his own pocket cash.

The final show in Tel Aviv leaves all involved emotional wrecks. An overcome Cohen simply stops mid-show, refusing to continue. Negotiations – including the audience collectively offering to sing the songs themselves – eventually lead to his return.

As fascinating as these side trips are, they’re distractions; the real focus is the music, which is sublime. Cohen manages to connect with the audience on a level rarely achieved by more seasoned performers.

As fascinating as these side trips are, they’re distractions; the real focus is the music, which is sublime. Cohen manages to connect with the audience on a level rarely achieved by more seasoned performers.

Yet there’s an incongruity; he appears at once deeply involved in the process, describing performing as a “holy experience,” and conversely, ready and willing to walk away from it all. The fact he has repeatedly done just that – including spending five years at a Buddhist monastery – shows he really could step away from the spotlight.

Bird On A Wire is one of the most fascinating tour documents ever made, yet until recently, few had even seen it. After an abbreviated theatrical run, the film remained unseen for almost 4 decades. The DVD release marks it’s commercial debut on any format.

Bird On A Wire is one of the most fascinating tour documents ever made, yet until recently, few had even seen it. After an abbreviated theatrical run, the film remained unseen for almost 4 decades. The DVD release marks it’s commercial debut on any format.

Songs From the Road opens with Cohen, age 75, onstage in Tel Aviv in 2009. It’s one of a dozen performances taken from his 2008/9 tour – his first in 15 years – which ran for two full years.

Despite the 35 year gap, there are consistencies; songs of love, mortality, transcendence and Biblical themes abound. As well, the back-up musicians Cohen employs are invariably impressive; there’s an almost telepathic support that enhances the readings in every case.

© John Cody 2010