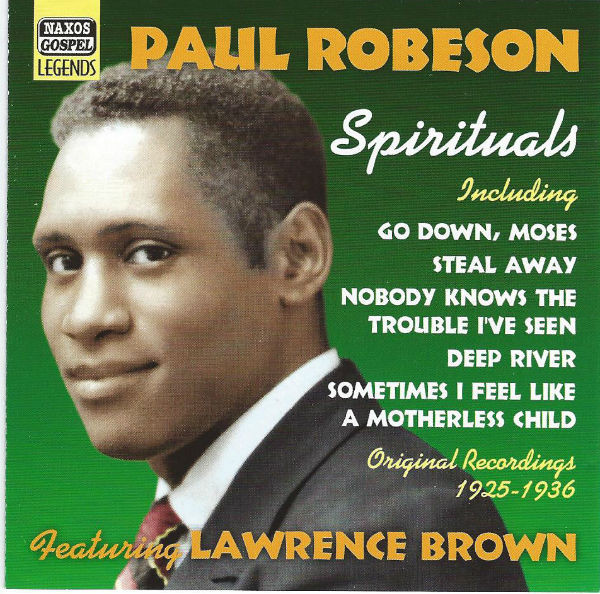

• Paul Robeson: Spirituals, Naxos, 2004.

THROUGHOUT his life, Paul Robeson battled the pervasive racism prevalent throughout much of the U.S. during the 20th century. His list of accomplishments is impressive, but he was best known as a singer.

Attending both Columbia and Rutgers University, he became an All-American football player but was frequently and aggressively tackled by his white teammates. He earned a law degree at Rutgers and graduated as valedictorian. Also an acclaimed stage actor, his lead in Eugene O’Neill’s Emperor Jones and his 1931 portrayal of Shakespeare’s Othello drew raves from British critics.

His father a runaway slave who became a Presbyterian preacher instilled in his son a life-long passion for truth and justice. On a visit to the White House, Robeson challenged President Harry Truman on his failure to pass anti-lynching laws. Because he demanded equal rights for blacks, his concerts frequently brought Ku Klux Klan demonstrations.

During the red scare of the fifties, Robeson who was sympathetic to communist ideals had his passport revoked, was barred from performing and was forced to endure electro-shock treatment. Yet he never wavered. His retained his dignity, and continued to work for the causes he so fervently believed in.

These recordings were made in London between 1925 and 1936. While he sang popular songs, he was most at home performing protest songs and spirituals; this collection is made up of the latter. While the material is moving, some of the titles are decidedly antiquated: ‘De Ole Ark’s a-Moverin’, ‘Sinner, Please Doan’ Let dis Harves’ Pass’ and ‘Hear de Lam’s a-Cryin” might raise a few eyebrows, but it’s the voice that counts and there’s never been anyone could sing quite like Robeson.

• Marian Anderson: Ev’ry Time I Feel the Spirit, Naxos, 2004.

The first popular black female vocalist, Marian Anderson used her powerful contralto to help break down walls for African Americans.

Starting out singing in the choir of the Union Baptist Church, Anderson showed great promise, and the church financed ongoing training. She came to popularity in the mid 1920s after singing with the New York Philharmonic. European tours brought further acclaim.

In 1938 she received an honorary Doctorate of Letters from Harvard University, and sang at the White House for President Roosevelt. The following year, the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow Anderson to appear at the Philharmonic Hall in Washington, D.C., citing their segregation clause. Reaction was swift first lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the organization, and a hastily arranged concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday brought an audience of 75,000. The concert was broadcast nationwide, and established Anderson as an icon in the fight toward racial harmony. A decade later, President Eisenhower appointed her U.S. delegate on the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations.

For the most part, her repertoire was limited to operatic material, but she customarily ended her recitals with spirituals. This collection, spanning 1930 to 1947, offers arias, songs and spirituals. Her voice, mannered by today’s standards, was once described by Arturo Toscanini as a voice that “is heard but once in 100 years.”

• Mavis Staples: Have a Little Faith, Alligator, 2004.

As lead vocalist in the Staple Singers, Mavis Staples, along with her father Pops, brother and two sisters, started out singing straight gospel. In the sixties, they incorporated folk and soul music.

Appearing frequently at Martin Luther King’s rallies, they became voices for the civil rights movement. During the seventies, songs such as ‘Respect Yourself’ and ‘Be What You Are’ addressed social issues informed by the gospel, and placed high on the charts including two number one pop hits. The group continued into the 1990s, prior to Pops’ passing in 2000.

Have A Little Faith boasts excellent production from Staples and Jim Tullio (the Band, Richie Havens). Arrangements are rooted in soul and gospel, with plenty of space. The opening track, ‘Step Into the Light’ features British guitar legend John Martyn. ‘Pop’s Recipe’ tells of her father’s sagely advice: “accept responsibility / Don’t forget humility / At every opportunity / Serve your artistry / Don’t subscribe to bigotry, hypocrisy, duplicity / Respect humanity / That’s pop’s recipe.”

In the liner notes Staples observes “these are the type of songs we sang down through the years positive songs, informative songs that help people through their lives. People are burdened down today, but if you have faith you can do it.”

The disc ends with ‘Will the Circle Be Unbroken’ which was the first song her father ever taught her.

© John Cody 2005