AT A TIME when a black man resides in the White House, it’s sobering to recall the not so distant past – when overt racism was accepted throughout most of America.

AT A TIME when a black man resides in the White House, it’s sobering to recall the not so distant past – when overt racism was accepted throughout most of America.

For the better part of the last century, blacks were relegated to the back of the bus, with beatings, and even legalized lynching imposed on those that challenged the status quo.

When Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger in 1955, it set in motion a sea change. Alabama’s policy of segregated seating on public transit was outlawed the following year; but the decision was met with derision, and sparked violent reprisals. Snipers fired on buses, and the home of Baptist Pastor Ralph Abernathy – one of the Civil Rights movement’s key leaders – was bombed.

While it would be folly to pretend racism has been eradicated, there’s no denying the massive strides made over the last century.

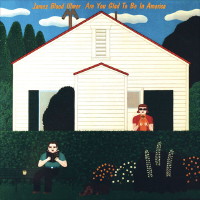

Let Freedom Sing, a new film and separately available 3-CD box set, explores the songs that inspired the movement. No other political faction valued and incorporated such a wide variety of music. Songwriters documented the struggle, and offered much needed emotional support for those in the trenches.

It’s hard to underestimate the role music played. In the film, Freedom Riders tell of being jailed, deprived of food, water and even toilets. Their only recourse was to sing. The music brought a sense of empowerment; as one Rider explains – the music could somehow make you a better person.

(Phil Ochs Archive)

When a white supremacist threatened to extinguish his cigarette on her face, a black woman recalls the song ‘I Shall Not Be Moved’ echoing in her mind, giving her strength and courage to stand her ground – courage the supremacist picked up on, and subsequently left her alone.

Spanning 1939 to present day, the variety of music is astounding; jazz, rock, funk, rap, reggae, blues and more, sharing the same message. There are anthems; from Mahalia Jackson singing ‘We Shall Overcome’ to Bob Dylan’s ‘Blowin’ In the Wind’ to Bob Marley’s ‘Get Up Stand Up’; songs that hit the top 10 pop charts by Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Marvin Gaye and Isley Brothers; all the way to the underground, with songs rarely, if ever, heard on radio.

The box begins (‘Go Down Moses’) and ends (‘Free At Last’ by the Blind Boys of Alabama) with straight ahead gospel; and there’s plenty more – the Jubilee Hummingbirds, Staple Singers, Harmonizing Four, the Mighty Clouds of Joy – in between.

That should come as no surprise, as the Civil Rights movement was birthed and nurtured in the church. Leaders invariably came out of the church; and in the south especially, the story of the Israelite slaves leaving Egypt for the Promised Land was easy to relate to.

(Photo by Terry Cryer)

The movement would eventually expand to the masses, but the teachings of non-violence and equality remained integral. As with all folk traditions, songs would occasionally receive updated lyrics specific to the cause. More often than not, the roots remained, and the gospel message came across even in pop hits like ‘People Get Ready.’ Many, like The Golden Gate Quartet’s ‘No Restrictions Signs In Heaven,’ Big Bill Broonzy’s ‘When Do I Get To Be Called A Man?’ and Curtis Mayfield’s ‘We The People Who Are Darker Than Blue,’ pack an emotional wallop. Others – Ray Scott’s ‘The Prayer’ (“Oh Lord, let the Governor have a 17 car accident with a gasoline truck that’s been hit by a match wagon over the Grand Canyon”) and Oscar Brown Jr.’s ‘Forty Acres and a Mule’ use humor to make their point.

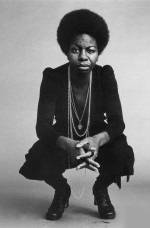

Some seethe with anger and indignation. Nina Simone wrote ‘Mississippi Goddam,’ in response to a Sunday morning church bombing in Birmingham that left four young girls dead. Billie Holiday’s harrowing ‘Strange Fruit,’ came out on a small independent label after Columbia, her regular record label, refused to release it. Nat King Cole’s ‘We Are Americans Too’ was deemed unacceptable as well.

Recorded in May, 1956, a month after he was assaulted on stage while performing before a Whites Only audience in Alabama, Capitol Records simply refused to put it out. The recording finally became available a half century later.

More recent material is conspicuous in its absence. Of the 58 tracks, just 3 come from the 80s-90s. There are five tracks included from the last decade, but it’s more of a look back; in all but one case the players have been recording for half a century, the other is a choir.

Maybe that’s a good thing; conditions had improved to the point where artists were addressing other issues – which is a sad irony. When conditions were at their worst, the music was inspired. Thankfully, it’s a genre that is becoming more and more obsolete.

The Civil Rights movement brought together people of all colors and walks of life, and the music was just as diverse. That diversity guarantees – unlike some compilations dedicated to a single theme – that listening to this release never becomes a chore. The quality stands strictly on musical merit.

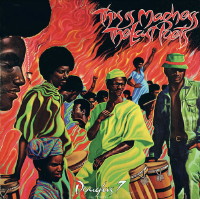

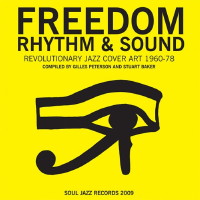

COMPRISING TWO separate-but-related releases, Freedom, Rhythm & Sound: Revolutionary Jazz and the Civil Rights Movement 1963-1982 employs a similar approach to Let Freedom Sing. In this case, with a two-CD set, and a 12 x 12 hardbound book showcasing LP artwork.

COMPRISING TWO separate-but-related releases, Freedom, Rhythm & Sound: Revolutionary Jazz and the Civil Rights Movement 1963-1982 employs a similar approach to Let Freedom Sing. In this case, with a two-CD set, and a 12 x 12 hardbound book showcasing LP artwork.

The timeline – twenty years – is more concise, as is the music itself. The majority comes from the seventies, and according to the compilers, the focus is on the avant-garde/free jazz sound birthed in the sixties. But that’s just a starting point; in some ways, the description is misleading, and could potentially turn off listeners leery of the term.

Rather than self-indulgent meanderings, these are tight, melodic and invariably powerful examples of a vibrant movement.

The mandate included economic and – just as importantly – musical independence. Initially, inspiration came from Rev Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. After both leaders were assassinated, the radicalized Black Power movement – which emphasized self-reliance in all areas – grew in popularity.

That Afro-centric world view is front and centre on tracks like Oliver Lake’s ‘Africa,’ ‘The African Look,’ and ‘Black Survival,’ but gospel roots are just as evident.

The Art Ensemble of Chicago’s take on ‘Old Time Religion’ shows just how close the ties to the church could be, and ‘Yes Lord,’ (by Gato Barbieri and Dollar Brand), and Michael White’s ‘The Blessing Song’ reference the gospel story to varying degrees.

‘Peyote Song No. III’ and ‘Big Spliff’ allude to drug use. Contrary to what came later -and tore the community apart – some drugs were viewed as mind expanding, with spiritual qualities. That hardly implied blanket acceptance; from Charlie Parker on, heroin had taken out some of the best and brightest players, and many in the movement preached abstinence. As ‘The Drinking Song’ by Gary Bartz Ntu Troop, admonishes; “never will be a revolution while you’re drinking wine/never will see a revelation while you’re drinking wine.”

Archie Shepp’s ‘Attica Blues’ addressed specific political issues, as does Sun Ra’s ‘Nuclear War,’ with the simple truth;”If they push that button, you can kiss your ass goodbye.”

In spite of the demands for change and equality, the jazz scene remained one of the last bastions of traditional male-domination. By the early 70s, the women’s movement was making great strides, yet, tellingly, of the 23 acts here, only two are fronted by women.

Mary Lou Williams had already secured her reputation through working with heavyweights like Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman and Dizzy Gillespie. After a self-imposed religious sabbatical, she returned to compose a number of works that addressed spiritual issues. ‘Miss D.D.’ from her groundbreaking 1963 release Black Christ Of the Andes is typical, with a unique sound bordering on exotica.

Amina Claudine Myers came up in gospel groups, and offers a swinging workout on organ that – like so much here -leaves the listener hungry for more.

Amina Claudine Myers came up in gospel groups, and offers a swinging workout on organ that – like so much here -leaves the listener hungry for more.

The handful of names already mentioned might ring a bell, but for the most part, this was truly an underground movement; one with zero commercial potential. Foreshadowing the D.I.Y. ethos almost a decade before the punk movement, the majority of music came out independently, pressed and sold via labels set up by the musicians themselves.

That’s where the book really shines. The description, “Radical Art For Radical Music,” is right on the money. With full size graphics, the artwork – which reflected the ethos of the movement – is presented in the best possible light. Running almost 200 pages, the length and format allows for a generous sampling.

That’s where the book really shines. The description, “Radical Art For Radical Music,” is right on the money. With full size graphics, the artwork – which reflected the ethos of the movement – is presented in the best possible light. Running almost 200 pages, the length and format allows for a generous sampling.

By the eighties, the scene was pretty much dead, and jazz was once again mainstream. Major labels were happy to sign the new traditionalists like Wynton Marsalis, who offered regressive – and far safer – product.

More’s the pity. Decades on, this music; creative, vibrant, and with a tangible sense of joy, stands on its own, in stark contrast to what came after.

For anyone interested, a first rate sampler of a scene ignored by most the first time round.

© John Cody 2010