In the history books of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Dion DiMucci stands out as an extraordinary figure. His list of credentials could easily fill this article. A condensed version might include the following:

The only artist to stay consistently interesting throughout a long and varied career, he’s appeared on the Billboard sales charts during the 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s. Chances are good his latest release Bronx in Blue will make it six decades in a row.

The Rolling Stone Album Guide lists him as ‘Exhibit A in defense of rock & roll in the years post-1958 and pre-1964.’ Those were the lean years. Little Richard joined the ministry, Chuck Berry went to jail, Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran died, and Elvis joined the army. It’s generally accepted that until the Beatles brought the British Invasion to America, there was precious little bona fide rock ‘n’ roll being made. Dion, Phil Spector, Del Shannon and others show that to be a fallacy. None more than Dion.

Record Collector magazine labeled him “Contender for the coolest guy in the known universe.” Billboard says he’s “the man who invented the rock ‘n’ roll attitude.”

When the original rockers began treading the rock ‘n’ roll oldies circuit in the late sixties, Dion refused to trade on past glories. Reinventing himself as folk troubadour with ‘Abraham, Martin and John,’ he produced a song that defined America’s sense of loss during its most turbulent decade.

He shows up with six different titles in The Heart of Rock & Soul: The 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made, but even his more obscure recordings are well worth seeking out.

Waiting for the Man: The Story of Drugs and Popular Music (1999) calls his 1968 single ‘Your Own Backyard’ “the most personal and straightforward song about drug problems ever released.”

Born To Be With You, a 1975 album produced by Wall of Sound architect Phil Spector, was all but disowned by Dion, yet Pete Townsend declared it the greatest album he’s ever heard.

Bruce Springsteen has claimed he’s the only artist who could fit into the Rat Pack and the ‘E’ Street Band with equal ease.

Inducting him into The R&R Hall of Fame in 1989, Lou Reed posed the rhetorical question “who could be hipper than Dion?”

He’s even appeared on Oprah. In short, he’s a living legend.

I spoke with Dion from his home in Boca Raton, Florida, recently, ostensibly about his latest release, Bronx In Blue, but the conversation continued for a couple of hours as we covered a wide range of subjects. He’s passionate about his life, his family, and especially his faith. Almost two hours into our conversation, he remarked; “I could talk to you forever on this, ‘cause it’s my favorite subject. You start talking about Jesus, you know…”

DiMucci was born in 1939, and grew up in the Bronx, one of New York’s toughest districts. He dropped out of school in his early teens and joined the Fordham Daggers, a local street gang.

He also sang on the street corners.

On a whim, he auditioned for a small record label when he was eighteen. They liked what they heard, and put his voice on a pre-recorded track. Released as Dion & the Timberlanes, the disc was nothing special – too polite – and rightly flopped. Vowing he could do better, he recruited three friends from the neighborhood, all members of a rival gang, the Imperial Hoods. Taking their name from Belmont Ave – a section of ‘Little Italy’ in the Bronx – Dion and the Belmonts were born.

After one tentative release, the quartet signed with upstart Laurie Records, and in spring 1958 scored a hit their first time out with ‘I Wonder Why.’

It was a revelation. Dion’s once-in-a-lifetime voice, tough guy bravado mixed with a tangible sense of joy and just a hint of vulnerability, was surrounded by doo-woppers of the highest order. The song was a clarion call, letting the world know the new sound had arrived, and it boasted pure street corner credibility. According to Charlie Gillett’s seminal The Sound of the City “Suddenly the street hoodlums of New York had a voice of their own.” Dion described it to me as “black music filtered through an Italian neighborhood, and it comes out with an attitude.”

In fact, many listeners thought they were black. That same year they became the first white group to ever play the famed Apollo Theatre in Harlem.

With a few hits under their belt, the Belmonts were part of the Winter Dance Party tour of February ‘59. Headlining alongside Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper and Richie Valens, the troupe traveled in a dilapidated bus through a brutally cold winter. At one stop Holly asked Dion to help share in the cost of hiring a small plane to fly ahead to the next town. He declined, avoiding certain death when the three other headliners perished after the plane crashed in a snowstorm outside of Mason City, Iowa.

Upon hearing the news of his companion’s demise, he sensed that God had spared him. For the first time in his life, he felt that God had a plan for him.

Meanwhile, the hits continued with tracks like ‘A Teenager In Love’ and ‘Where or When’ placing high in the top ten.

After eight hit records with the Belmonts, DiMucci went solo in 1960. He had tired of what was becoming a formula. The group had begun to update old standards, and while sales remained strong, Dion wanted to do harder-edged material. They wanted smooth, he wanted to rock. And rock he did. The hits got even bigger – and better. ‘The Wanderer’ ‘Lovers Who Wander’ and ‘Little Diane’ were huge. ‘Runaround Sue’ made it all the way to number one.

Life was good. He was a millionaire, the public loved him, and his first and only girlfriend, Susan – who he met when they were both 11years old – was by his side. Not that there weren’t temptations. He freely admitted to womanizing, and drugs were a constant presence. But for the time being, everything appeared to be under control.

In 1962 his contract with Laurie expired and he signed with industry giant Columbia Records. He was the label’s first ever rock act, and for a while the hits continued, including ‘Donna The Prima Donna’ and first-rate renditions of two Drifters classics – ‘Ruby Baby,’ and ‘Drip Drop.’

He became friends with John Hammond, the legendary Columbia producer who had discovered Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Benny Goodman, Aretha Franklin, and Bob Dylan. The two never worked together in the studio, but Hammond had a profound effect on Dion. He played him a pre-release acetate of the Robert Johnson compilation King of the Delta Blues Singers, indisputably the most important acoustic folk blues album ever released. For DiMucci, already a fan of the blues – he had recorded Jimmy Reed’s ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’ for Laurie – it was like a light had been turned on. He began recording blues material by Willie Dixon, Sonny Boy Williamson, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sleepy John Estes and Big Joe Williams.

He was also a fan of label mate Bob Dylan, who was just starting his recording career when Dion signed with Columbia. He attended a few of Dylan’s recording sessions, and, figuring it would sound even better with a full band, convinced Dylan’s producer Tom Wilson to try an experiment: “We got a bunch of guys and we put them on ‘Maggie’s Farm.’ We took the Dylan record into the studio, and put these musicians on it. The song was already recorded, and we added [the band] just to show him. We had an idea that Dylan would like to hear more than his guitar. It wasn’t a demand, it was like a request, saying ‘listen to this, if you like it, maybe we could do more of it. If you don’t…chuck it.’”

Dylan loved it, and began using the band that Dion had put together on his sessions. He’s since credited Dion with helping him decide to go electric, and on occasion has performed ‘The Wanderer’ and ‘Abraham, Martin and John’ in concert.

That’s not his only contribution to the folk rock genre. According to Byrds leader Roger McGuinn, in early 1964 Dion heard him experimenting with a folk and Beatles hybrid, and told him he was on to something. The first industry professional to offer encouragement, Dion was adamant that McGuinn pursue the new sound. A year later the Byrds would be the biggest band in the country, topping the charts twice with electric versions of Dylan’s ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and ‘Turn, Turn, Turn,’ which was adapted from the Book of Ecclesiastes.

In order to be closer to the thriving Greenwich Village blues and folk scenes, DiMucci moved from the Bronx to Manhattan. In addition to the his own original folk-based material, he recorded songs by Dylan, Woody Guthrie and Tom Paxton while on Columbia.

By then he had also gotten to know many of the blues legends personally. He toured with Jimmy Reed, hung out and played guitar with Lightnin’ Hopkins and Rev Gary Davis, and Howlin’ Wolf had declared himself a fan after hearing Dion perform live.

By the mid-sixties, the British invasion had hit hard, and most of his contemporaries from the fifties had disappeared from the charts. Dion was one of the few American acts that didn’t feel threatened. “The English picked up on the roots of what I was doing. I never thought that you could go to the Brooklyn Fox in Brooklyn and sing like Mick Jagger. It would have almost been like an insult to the black guys. Like, [sings in an exaggerated Mick Jagger affectation] ‘I love you baby.’ It would have been like ‘what the hell are you doing?” It would have been like blackface. But in the sixties, from England, it started coming over, and I said ‘Wow, these guys are really picking up on my love.’ I don’t think a lot of American [acts] picked up on it. They didn’t. A lot of them just stopped in the sixties, and they stayed with the doo wop era”

For all of Dion’s interest in exploring new forms, the label choose to leave the majority of his folk and blues recordings in the can, pushing him instead towards what they referred to as ‘legitimate music.’ The blues revival was still a few years off, and they wanted a more traditional, all-round entertainer, ala Paul Anka or Bobby Vinton. The label brass just didn’t get it. “Oh, (long-time producer) Bob Mersey didn’t know anything about what I was doing. Just listen to ‘Be Careful of the Stones You Throw.’” A Hank Williams song, it should have been a natural, but missed the mark artistically and commercially. “You’d come in with a guitar and they’d mess it up, all those guys…the only stuff that they gave me control on was sometimes the stuff that I was writing or I picked up on. Like ‘The Wanderer’ and ‘Runaround Sue,’ or ‘Ruby Baby.’ I brought a song in and I said ‘You’re not touching this, I’m doing this.’ And those are the things that really worked. All this other peripheral stuff – it wasn’t really me, a lot of it. That’s why I left. They had no idea.”

The Columbia years produced some vital music, most of it unheard at the time. The label released a handful of singles, and no LPs after 1964. In the nineties, two excellent collections boasting unreleased material from this era were released on CD; Bronx Blues: The Columbia Recordings (1962-1965) and the double disc set The Road I’m On: A Retrospective.

By 1966, Dion left Columbia and disappeared from the limelight.

He was no longer on the scene, but he wasn’t forgotten. The Beatles’ 1967 opus Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band contained eighty six cardboard cut-outs of various celebrities on the album’s cover, each said to have impacted the Fab Four. Only two were popular musicians – Dion and Bob Dylan.

As the Beatles were ushering in the psychedelic Summer of Love with Sgt. Pepper’s, Dion was living in a drug hell.

Long before his career began, drugs were a constant in his life. He got drunk at twelve, smoked grass at thirteen, and began using heroin at fourteen years old.

He loved it.

“The first time I took a drug, I didn’t have to think. I felt so good. I didn’t have to second guess myself. ‘Should I feel this way?’ ‘Shouldn’t I feel this way?’ ‘What are you supposed to feel?’ I just felt good. It stopped the whirlwind in my head that I was brought up with. Because my parents argued a lot. That’s all they did was argue. They didn’t smoke, drink, do drugs. They didn’t even drink coffee. But they argued a lot. They were like emotional thirteen year olds.”

Throughout the hit years, his drug use increased dramatically. Ironically, the Columbia contract’s guaranteed annual payment of $100,000 meant he no longer had to worry about money or producing hit records. He could indulge in making the music he loved, and scoring more drugs.

It got ugly.

On one occasion recounted in his the autobiography The Wanderer (Beech Tree Books/William Morrow, 1988), he drives into Harlem looking to score heroin, with Susan – his now pregnant wife – by his side. For the first time she begins to cry, telling him she can’t take his addiction anymore. Dion kicks her out of the car, leaving her alone on the street to make her own way back home as he continues to search for a fix. Afterwards, he’s jumped by a gang while shooting up.

Drugs took precedence over everything. In and out of hospitals during the hit years, at one point he ended up in the psychiatric ward at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Later, high on acid and a fifth of scotch, he decided to commit suicide. He changed his mind, but continued to slide deeper into the abyss.

He finally bottomed out. At his wit’s end, on April 1, 1968 Dion took his father-in-law’s advice, and prayed to God for it to stop.

It did. Since that day, he’s been straight.

He began to see things in a different light, realizing that God can use all things for good. Even the negative memories were cast in a new light; “Here’s my parents, they argued every day over the rent because my father wasn’t working. That used to drive me up a wall. Meanwhile, it saved my life when I had to make a decision whether to get on the plane [with Buddy Holly] or not… ‘Wow, $36 it’s a whole month’s rent. I can’t do that. I’ll stay on the bus.’ So in a way, it saved my life.”

Career wise, things heated up almost immediately. In one of the great comebacks of the era, he returned to the upper reaches of the charts with ‘Abraham, Martin and John.’ Rolling Stone Record Guide calls the song “Perhaps the best, certainly the best received protest song of all.” Initially, no one was interested in releasing the song, so he returned to Laurie records.

To most of the public it seemed like a major change in direction, yet the seeds were sown long before, as evidenced by his unreleased Columbia recordings.

A year later he again left Laurie for a major label, this time signing with Warner Brothers. His debut album, 1970’s Sit Down Old Friend was just Dion and his guitar, performing mostly original material. One of the few covers was a take on Willie Dixon’s blues standard ‘You Can’t Judge A Book By its Cover.’ The new material reflected his changed outlook, with songs like ‘Let Go, Let God’ offering evidence of his sobriety. Concurrent with the album was a single-only release of ‘Your Own Backyard.’ A brutally honest depiction of getting straight, it garnered a rave review in Rolling Stone, but never sold. English rockers Mott the Hoople covered the song the following year, and it has since been recognized as one of Dion’s greatest compositions.

On his web site he refers to entering a “Spiritual-based 12 Step Program.” He’s happy to talk about his recovery, but unwilling to go on record as to exactly which program this is.

He believes substance abuse has gotten worse since he stopped. “This culture is so filled with drugs. You take a drug for everything. So people never really hit a bottom, emotionally. Like a nervous breakdown is a bad thing, so you try to prevent it – when [in fact], it’s a good thing. If you drive yourself to the end, you’ll find God.” He asserts that it does more harm than good to try and cushion the blows. For many addicts, the only chance of getting well is to hit bottom. “They say pain is the touchstone of spiritual growth. You’ve got to lean into it. You don’t pull away from it. If you pull away from it, and you start taking a drug, or you find another way to mask it, you’ll never really come into this higher reality. Which is so beautiful to be living in.”

Once he got straight, it had to be 100%. He knew all about public versus private persona; “I knew a guy early on, and…it really taught me something. He was a bigwig in the recovery movement – I don’t want to mention his name. When he died, the place was jammed, because he was looked at as a guru. And yet, his wife was sitting on the front row. His girlfriend was on the side. He had two girlfriends in the back. And there was a funny feeling in the room for me. And I wondered about that. I said, ‘I don’t want to die like this.’ I learned that the guru thing didn’t fly with me. You know why? I’m in show business. Just think about it. It’s the business of show. I grew up like that.

“It’s like my dad. [at his funeral] They all got up and everybody eulogized him and said how funny he was and what he did, and all the stuff they mentioned was what had kept him from us. All of the stuff they mentioned.

“My father used to talk to an insurance guy who would come over to the house when I was a kid. And then he’d leave, and he’d kick us. But he was so nice to him. You get that kinda thing where they’re on to the outside world, but they don’t really know how to be intimate. They’re too frightened. And that will keep you away from God for sure. Because that’s the most intimate you can get. To feel that kind of love is just overwhelming.

During the seventies he released half a dozen albums in the singer/songwriter folk vein for Warner, all of which garnered critical praise while failing to sell in significant numbers. These are harder to come by, but well worth seeking out. Ace Records in the U.K. has released all six albums on CD.

By 1979 Dion had been sober for over a decade, when his neighbor, a Baptist music minister, started asking some hard questions. “He asked me ‘did you make a decision?’ He kind of cornered me, and asked me some very specific questions. It confused me a little. And I said “God, it would be nice to be closer to you.” And ‘Bing,’ the lights went on. And God’s the only one who can do it.” He began attending church and studying the Bible.

He experienced a paradigm shift. “I never knew how to think until I came into the church. That’s not a popular idea in a lot of areas. They look at it like you threw away your brains. I was telling somebody the other day – they were saying ‘you don’t have to think anymore.’ I said ‘You’ve got it wrong. Let me tell you something. You can’t get anymore free willed than I am.’ I said ‘I am a free person.’ And I never knew how free. I was trying to tell this guy, but he didn’t get it, so I said, ‘You know, there was a time when I was in love with the search for truth.’ Underline search. I said I was in love with the search. It made me look sensitive and thoughtful and brilliant… But when you come to the truth, when you’re a free person, and you come to the truth, do you receive it? Do you accept it? Do you embrace it? Or do you walk away from it? So I said, ‘I’ve accepted this out of my free will. I love the church out of my free will. No one manipulated me. No one’s manipulating me now. I have free will. So I accept truth. To live by it you have to think more. I’ve accepted it.’ I was telling him, as a free person, if you come to truth, if you walk into the person, or God who embodies all truth, would you accept it? Would you embrace it? Would you live your life by it? Would you adore it? Or would you walk away from it and do your own thing?”

Over the next 18 years he enjoyed close ties with Chuck Smith at Calvary Temple and Greg Laurie from Harvest Christian Fellowship, both popular Evangelical churches.

He began recording Gospel music exclusively in 1980. “When I had my conversion experience, I thought, whoa, God is the center of the world. He is the center of the universe. The center of history. He’s the center of life. I’ve never wavered from that. I understand that big time. So that was the center of my life, and I wrote a song called ‘Center of my Life.’ And that started it.”

He released five gospel albums, all of which were well-received within the Christian community. 1983’s I Put Away My Idols was nominated for a Grammy in the Contemporary Gospel category, and the song ‘Simple Ironies’ spent two weeks at the number one position on Christian radio in 1986.

That same year he decided to leave the Christian music scene. “Well, you gotta understand. It is the Christian. Period. Music. Period. Business. Period. So, a third Christian, a third music, and a third business. Sometimes the business thing might get a little [out of hand], or the music might [suffer], but for the most part it was a positive thing. I met wonderful, wonderful musicians with great hearts and love for the Lord, and wonderful Pastors all over the country, and Australia and even in Canada. It was a great positive experience for me. Loved it.”

But it was time to move on. “I got the feeling the Lord was leading me to embrace my whole story, like the Apostle Paul. He used everything he was about. He never hid anything. He used when he was a sinner, when he was part of persecuting the members of the church. He never hid it. So, I thought, I’m gonna just kinda put the past, the present, and the future together where I can get out in front of people and share what’s going on in my life. Where I came from, what happened, and what I’m like now. So I kinda use it, I keep it very centered on my faith.”

I mentioned that in talking with other musicians who had left the Christian music scene, including Mark Farner and Buddy Miller, a common complaint was of the business end being even shadier than in the mainstream world. Dion readily agreed, laughing, “Well, there you go… evidence.”

“I had some negative things. The church never hurts you, but members in the church sometimes do…Some of those fundamentalist churches and denominations kinda make a demand. Like a lot of them don’t even want you to go into [Twelve step programs]. I was told by a fundamentalist preacher ‘don’t go, there’s demons there.’ I said, ‘Ha! that’s exactly why I go there. There’s demons in the church, if you want to put it that way. I said [these programs are] a harvest field. A lot of Christians are involved down here, and we’re very active in our church. Where two or more are gathered, there’s the Lord. And we infiltrate those meetings, because guys wanna quit drinking, but they don’t really know why they’re there. So we stay to give. And sometimes we’re very obvious about our faith.”

He has a heart for those who can’t seem to get better. “Some people… I don’t know. I don’t understand that. My heart breaks [for these people]. I don’t understand it. They don’t appropriate some truths. For instance, the idea of talking to somebody.” What he calls the ‘principal of opening your mouth.’

“What a tremendous principle. People who don’t grab onto that will blow their brains out… In a way that’s why I feel Jesus left us confession. In John chapter 20:23 he says ‘Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them. Whose sins you retain are retained.’ You have to hear them to forgive them or retain them. So he gave us confession. He gave his Apostles the authority to forgive. And he knew how important it was to hear that we’re forgiven. And to get them out of our mouths. There’s a principal there, about getting them out of your head, and letting another person hear it.”

Over the years Dion has counseled addicts and those new to the faith. “I just love talking to guys about faith. Because I’m a believer and my life is built on the rock, and I love talking to guys about it because nobody was that obvious with me when I was a kid.. There was a time I never thought I’d be able to talk about stuff like that. It’s my favorite thing to do.”

He’s absolutely passionate about his beliefs. “The reason why I have such a strong faith, [is that] I was confused for a long time, just looking for how to do life. When I finally walked into a church and got on my knees, and God answered a prayer, [everything changed]. I haven’t used a drug or drink for 38 years.”

And when it comes to helping others, he has know qualms about using his celebrity status: “I think it helps. Because people, they kinda know your track record, so they know you don’t have an ulterior motive. They know you’re not looking for money, or prestige. They know you don’t have an agenda other than to help…So in my case it helps.”

A well-publicized return to mainstream brought him back to the public’s eye in 1987. A recently released double CD set of his Radio City Music Hall performance titled Dion (& Friends) Live New York City (Collectibles) captures him in front of a frenzied audience, thrilled to have him back, and features songs from throughout his entire career up to that point.

A benefit show at Madison Square Garden later that year included vocal back-up from Bruce Springsteen, Lou Reed, Paul Simon, James Taylor and Billy Joel, all of whom have cited DiMucci as a major inspiration to their own careers.

His first album back, 1989’s Yo Frankie, was a magnificent return to form.

In many ways it’s even more inspiring than what he had released earlier in the decade. The message is less overt, but it’s obvious the Christian world view is still in effect. After bragging through most of the disc’s opener, ‘King of the New York Streets,’ the penny drops. “Yeah. [quoting song lyric]‘I was wise in my own eyes/I awoke one day and I realized/this attitude comes from cocaine lies/King of the New York streets.’ There’s a little nugget of the gospel in there. People hear it in there.”

In fact, the search for truth has been prominent throughout his entire career. I asked if he felt God was working through him, even if he wasn’t aware of it at the time. “Absolutely. Absolutely…Even ‘The Wanderer’ has it in there. It says ‘I roam from town to town/I go through life without a care/I’m as happy as a clown/with my two fists of iron/I’m goin’ nowhere.’ It’s like a thin veneer of being a man. You’re saying with my two fists of iron and my bottle of beer – how many guys try to be a man like that? It’s nothing. So basically, even that song turns in on itself.”

I mention ‘(I Was) Born To Cry,’ from 1962; “Yeah. That’s amazing, because I wrote that when I was seventeen. And [Swedish garage punks] the Hives just did it. They have it on two videos. It’s really interesting that they picked up on it.” The song’s lyric is almost Biblical, reminiscent of the Book or Lamentations: ‘I wish today the world/my friends would stop being sad/There’s so much evil ‘round us/I feel that I could die/I know some day and maybe soon/that Master will call/and when he does I’ll tell you something/I won’t cry.’ “It’s amazing…that’s a song that I did when I was seventeen.”

Live, Dion’s faith continues to impact his performances. “If I go out and do a show, I gotta talk about my faith and do a couple of songs about that. I try to infiltrate the culture. You don’t want to bounce people on the head with it. I might say that when I got three daughters, I was wondering how to keep my family together, and I decided to put the church at the center of my life. And I wrote this song, and I’ll sing ‘Center of My Life.’ About Jesus. But I’m talking about me and my family.”

He continued to release albums through the nineties, including Rock n’ Roll Christmas, an underrated Christmas album.

While the music end was business as usual, something bigger was brewing.

Unsatisfied with answers that seemed to lean towards a subjective truth, he began studying the early church writings. As he studied, he found he had even more questions. Particularly around authority, and why, if there is one true church, there are so many denominations. “As far as I know, there’s over 30,000 denominations outside the Catholic. As I read scripture I came upon some verses that I needed answers for. I would go around and ask people, ‘what’s the foundation of truth?’ and they had all kinds of answers. But the Bible says it’s the church. The pillar and foundation of truth is the church. What church? Because if you get five protestant churches, and they [each] teach different on baptism, and the Lord’s Supper… So I said, ‘Which one?’

“I started reading, and I started seeing where the Bible came from, that Saint Augustine headed up this illustrious council in Hippo and Carthage, and the church chose the books. So the Bible didn’t form the church, the church formed the Bible. I said ‘wow.’ I went back and started reading guys that Peter and John ordained, like Polycarp and Ignatius – who knew John.

“When I started reading early Christianity, I saw the Catholic Church. I didn’t see denominations like these American denominations that to me became a thin veneer of who Jesus was. It gave me more depth. It led me right to the church. Then I started to see why I had a physical father, a heavenly father, and I needed a spiritual father – at the time it was John Paul II – to keep me on track. Because if you’re in Protestant denominations, to be honest with you, it doesn’t work, they’re all over the place. I mean there’s a lot of good stuff, don’t get me wrong. I know they’re Christians. I know they’re blessed, sweet people in the Lord. And they’re doing the best they could. But they don’t have the fullness of the faith, as far as I was concerned.

“There was a saying I used to hear in Calvary Chapel, and in the Presbyterian church. They used to say ‘Unity in the essential, liberty in the non-essentials, and love and charity in all things.’ So I thought I knew what the essentials were. Then I found out that it was a Saint Augustine quote – who put the bible together. And what he meant by the essentials, was baptism and authority and the Eucharist. I thought it was the Virgin birth, and the crucifixion. And when I read what he thought about it I said, “Wow… authority… who would think?

“Then it started to dawn on me, even the constitution, if you just hand it out to everybody and say everybody go for themselves, and you don’t have a Supreme Court, what does it mean? You can make it mean anything. Today, in most churches, or most Protestant churches, you could hand out bibles, you could start churches with just the book. You and I could start a church. We could call it the ‘World Unity Church,’ because you come from Canada, I come from the U.S. And we could teach, and we’d probably get a lot of stuff right. But would we be in the fullness? No. Because there’s two thousand years of history, and there’s a passing down…

“Then I went to G.K. Chesterton…He was Catholic and I started looking at what he was saying about Catholicism, and I’m telling you… C.S. Lewis, [Chesterton] , these guys are my heroes. I love these guys.”

“Then I found a website, The Journey Home. It’s on a Catholic network here called EWTN. The Eternal Word Television Network. I started calling them, and they helped me with some things, because I didn’t understand a lot of things. Especially Mary. You go into a Protestant church it’s like almost void of anything… and Mary is His Mother. She must have some significance. Come on. And you would hear that Catholics would worship Mary. They don’t. They just reverence her in a very special way. It’s interesting when you look at Catholic doctrine or Catholic teaching, and you don’t come in with any prejudice, just let the Holy Spirit [lead you].

“The website has brought about three hundred Pastors into the Catholic church. Because they wanted to know what it taught, and they sent them the literature. Because with Catholicism, you can’t shuck and jive what it teaches. They have a Catechism. It’s two thousand years of teaching that’s never changed. It’s right there in the Catechism, everything that they teach. You could look it up in the back, and find out, you look up salvation, what you believe on salvation. A lot of people think Catholics believe that you’re saved by works. That’s the kind of thing that they loosely throw around. But it’s not that. You’re saved by grace through faith. But certainly works are involved. He says when you do to the least of these you do it to me. So you visit the people in jail. You feed the hungry. Some things are necessary – they’re not necessary for salvation, but working out your salvation. We’re saved, we’re being saved, and we will be saved.”

In 1997 Dion returned to the Catholic church. He went to Mount Carmel Church the same church where he had been baptized in 1939.

I wondered how old friends from the Evangelical days, like Jack Hayford and Greg Laurie, felt about his re-embracing Catholicism: “They love me. Those guys – Greg just called me, he said, “I saw your video, boy you still got it.” He just loves me -and I love him. You wanna know – anything I say in that area of Catholicism, we talk theology, it has nothing to do with my love for you as a brother in Christ. It’s like a debate that’s over here on the shelf, we could talk about these things, but it has nothing to do with my connection with you as family in Christ. That’s the way I see it. I just think we all have to go deeper – I don’t know where I am on the journey. I don’t want to get arrogant or [suggest you should] believe and think and be like me. That’s totally arrogant. It’s just stuff that I read and helped me. I just want to get closer to God…

“As far as I was concerned, I thought Catholics were off the runway. I was anti-Catholic. I was in Calvary Chapel a long time. And I gotta say this, it was such a blessing, because they taught me scripture. I could sit down with any pastor in town, because I know my faith, and I know the scriptures. I can get around the scriptures, and I could show them in the scriptures. But there’s a lot of scriptures they ignore. And the Catholic Church don’t ignore any scriptures. It’s a Catholic book. Anyway, I get crazy on that. Because it was a long journey…”

He began to see old wounds heal. “I was praying in Italy, in Rome. I was in the church of St. Peter in Chains. It seemed like I was the only one in the church. And this strong sense of praying for my dad came over me. To offer up this tremendous amount of grace to his life. And it wasn’t like I was coming up with it. I didn’t want to waste it on him. I was kind of angry. Not angry to the point of ruining my life. But if I thought of my father it was like thinking of my second grade teacher who I’d forgot. There was no emotion attached to it. He came, he went. I kinda love him, you know, but it’s sad. But now, after that experience I had in that church, I can tell you that I love my father. Not like a little bit – I love my father.

“I talked to Father Joe about it and he said ‘Dion, you know, relationships don’t end.’ I’m hesitant to mention Purgatory to you, but Jesus, when he preached to the souls, it was kind of a mid-place. It wasn’t Heaven, it wasn’t Hell. It was kind of a mid-place. Scripturally – and the Jews knew this – there’s a place of purging. I shouldn’t even call it a place. It’s a state. You kind of walk through. In 1Corinthians, in the first chapter it talks about when we stand before the Lord we’ll be saved. Everything made of wood and stubble and hay will burn up. And we’ll be refined through a fire. We will be saved, but what wasn’t true and didn’t come through Christ will be burnt up. So it’s a state that you go through, it’s almost like a shower, before you meet the Lord. You can’t go from here to there without cleaning up that selfishness that we still have. So they call it a purgatory. Like a purging. Being on earth is like Purgatory. We die to ourselves, and it continues in Catholicism. They claim that relationships don’t really end. Just because your father’s dead, doesn’t mean you can’t have a relation. Because someday you’ll be seeing him. So you keep that going, and hopefully on the day you see him that relationship would move along, instead of just thinking ‘well he’s gone, that’s over.’ It’s not over. It’s gonna continue.”

His newest release, Bronx in Blue is a simple, yet powerful statement. Just Dion and his acoustic guitar, with minimal percussion, doing Chicago and Delta blues. The album features classics by Willie Dixon, Jimmy Reed, Howlin’ Wolf, and other blues legends, as well as Hank Williams’ ‘Honky Tonk Blues’ and two originals.

At sixty six, he’s not slowed down a bit. His voice is as strong as ever, and stripped down, songs like Bo Diddley’s ‘Who Do You Love’ drip attitude.

“Basically everything that’s on the new album was the cause for me doing everything else. It was the cause for me getting in the business. It was the cause for me wanting to write and express myself. It was the cause for me wanting to communicate, wanting to take people on a trip because that music took me on a trip. It was the undercurrent of all those [songs]. If you hear the new album, there’s not a false moment on it. I’m just doin’ it. It’s stuff that’s been in my head and in my guitar for fifty years.”

In addition to his vocalizing, Dion is a formidable guitarist. He played on all of his records, but during the hit years record companies rarely allowed him to be photographed with his guitar, preferring to sell him as a teen idol.

Early reviews have been enthusiastic across the board. Vintage Guitar Magazine wrote “It actually sounds more authentic, less affected than dozens of albums by established blues artists of any color or genre." No Depression received an early pressing, and even though it wasn’t officially released until this year, named it best traditional blues album of 2005.

From the beginning, the blues have always been a vital ingredient to Dion’s sound, so a straight-ahead blues album seems like an obvious idea. “People over the years” – including friends Bonnie Raitt, Steve Van Zandt and Van Morrison – “have always told me that, because it’s music I sing in the dressing room, or at home.”

His very first LP, 1959’s Presenting Dion and the Belmonts, included ‘I Got the Blues.’ He recently pointed out that ‘The Wanderer’ is simply the white version of Muddy Water’s ‘Mannish Boy.’ His adaptation of ‘Ruby Baby’ was in large part built around John Lee Hooker’s ‘Walkin’ the Boogie.’ Many of his hits, like ‘Lovers Who Wander’ and ‘Drip Drop’ are blues-based.

He first recorded Lightning Hopkins’ ‘You Better Watch Yourself’ on his self-titled album in 1968. As good as the earlier performance was, it’s even better in this new version.

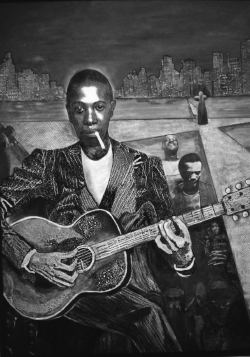

His love of Robert Johnson’s music is readily apparent – there are four Johnson songs here – including ‘Crossroads,’ to which he’s added new lyrics about salvation. Dion is also a gifted painter, and the disc’s booklet includes an impressive portrait of the man that he painted a few years back.

“It’s a blues album, and as a Christian, sometimes you hear some of these blues things and you think, ‘wow, this music is moving away from God, it’s not moving towards God.’ But it shows you that there’s a center. To me the blues is the naked cry of the human heart, apart from God. We lost that connection somewhere in the garden. There’s an honest cry there with a lot of them. I’m not saying in all of it. There’s a real cry. Especially from the period that music was written in. It was horrendous. There’s a real love for the blues from me. As an art form. And I’ve been through some of that. We all have. You don’t have to be black and from the 30’s to have the blues.”

These are songs he’s sung for years.

Hank Williams’ ‘Honky Tonk Blues’ – a country number that fits in remarkably well – goes all the way back to the beginning. He claims it’s the first song he ever heard, and the first song he ever learned.

He was ten years old, and it was a powerful introduction to the country icon’s music. “I knew sixty Hank Williams songs by the age of fourteen.” Williams is still his biggest single influence: “If I had to boil it down to one guy, yeah. When somebody influences you that strongly, in those real, impressionable, vulnerable, tender years… it’s autographed in your mind forever. It’s just so significant, so monumental.”

So why not an album of Hank’s songs? “Country music is popular, and people get on the bandwagon, so it kind of leaves a bad taste in the mouth. I toyed with the idea, because, again, it’s my roots. It’s probably more my roots than Italian music. Hank Williams was the cause of me getting in the business. Him and Jimmy Reed, but I tell ya, I knew more Hank Williams songs…he was my idol.” I mention Hank’s claim that he didn’t sing country music – he called his music ‘folk music: music for the folks.’ Dion laughs, “That’s good. That’s good. Well, that’s what I do. I like to take people on a trip. Songs. As a kid, when you hear that song that does something to your insides, it’s hard to explain, but I love it. And I wanted to be part of that. That explains it. People’s music.”

Just like he borrowed from the blues, he would transfer Williams’ ideas into street corner lingo for his own material. Williams’ sometimes dark subject matter, dealing with deceit, desire, and the shadier side of life, was the inspiration for such hits as ‘Lovers Who Wander,’ ‘Love Came To Me,’ ‘(I Was) Born To Cry,’ and ‘Lonely Teenager.’ He cites Williams’ lyric ‘Baby, I still want you/you step all over me/badmouth me to my friends’ as the basis for his 1962 hit ‘Little Diane.’ Even ‘Your Own Back Yard’ could fit into the Williams canon, as a word of warning from Hank’s alter ego, Luke the Drifter.

Ray Charles and Johnny Cash arrived during the same era as Dion. Both struggled with long term addictions, and each had their stories told on the silver screen recently. It’s no surprise that a film based on Dion’s life has been in the works for almost a decade. “Barry Levinson (Diner/Rain Man) put a script together. Chazz Palminteri (A Bronx Tale) wrote a script with MGM. They had some troubles, so that never came to pass.”

He’s concerned that the Cash film (I Walk the Line) downplayed the Man in Black’s faith. "They kinda tossed that part of it off. Towards the end he’s walking to church… that was about his bad ass years. So I’m working on one from the ground, a grass roots kinda deal. I’m working with a guy now, we’re almost finished with the script.” And it would include his faith journey. “What other reason for doing it? That would have to be part of it. Absolutely.” He knows that will make it a harder sell, but plans to stick to his guns. “You can see how Mel Gibson had such a struggle when he tried to do it [with The Passion]. It was very controversial. You mention Jesus – Jesus said “I didn’t come to bring peace. I’m gonna divide people.” So we’re with him.”

One word Dion uses a lot when expressing his feelings about faith, family, friends and music, is ‘love.’ Despite his illustrious past, it’s clear that the deepest passion and joy comes not from a storied career, but something far more personal. Before our conversation comes to an end he mentions that he feels truly blessed. Dion and his wife Susan will be celebrating their forty third wedding anniversary next month.

“I did feel like God had a plan for my life. It’s why I have my journey on my web site…Just to pass it on. That Jesus is the center of life, and the world, and history. His story. That plan for me is to just grow closer to Him, go deeper every day. Less of me, and more of Him. And to pass it on. And the rest falls in a pretty lovely way for me, if I’m centered, and I’m focused in that.”

© John Cody 2006