• The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film, by Richie Unterberger, Backbeat/Hal Leonard

• Beatles Gear, Revised Edition, by Andy Babiuk, Backbeat/Hal Leonard

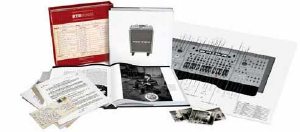

• Recording The Beatles, by Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew, Curvebender Publishing

• Lennon & McCartney: Together Alone A Critical Discography of Their Solo Work, by John Blaney, Jawbone

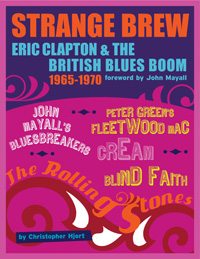

• Strange Brew: Eric Clapton and the British Blues Boom 1965-1970, by Christoper Hjort, Jawbone

If there’s one band that’s been covered to excess it’s the Beatles. Books on every conceivable facet of their lives and careers are available. The following – covering everything from the band’s spiritual dynamic to the type of microphones they used – are a few of the better recently published titles.

In Beatles Gear, Andy Babiuk examines the instruments and amplifiers they used on stage and in the studio.

In Beatles Gear, Andy Babiuk examines the instruments and amplifiers they used on stage and in the studio.

There are apocryphal stories concerning musicians and their instruments; drumming legend Tony Williams’ ride cymbal was assumed to be one in a million, possessing a rich tone exclusive to that very cymbal. Once, after Williams had left his kit set up, another drummer snuck on stage and played it, only to discover that the cymbal sounded nothing like he had imagined. It was what Williams brought to the instrument, not the other way round.

In other words, it’s far more important who’s playing the instrument. Nevertheless, it’s fascinating for those so inclined to learn exactly what was played.

Babiuk starts with John’s first guitar from 1956 – a Gallotone Champion [‘guaranteed not to split’] – and continues on through every subsequent instrument up until their final recording sessions.

Whatever they played, everyone wanted. Gretsch couldn’t keep up with the demand after George started playing their guitars, and when Ringo was seen playing Ludwig drums on the Ed Sullivan Show, company orders skyrocketed, with the factory operating around the clock attempting to fill orders.

Illustrated with shots of pretty much every instrument they used, Beatles Gear is essential for any musician hoping to understand what went into the creating their sound.

Instead of the guitars and drums, Recording The Beatles offers a spectacularly in-depth look at the gear they recorded on. It’s a phenomenal achievement, detailing the mikes, mixers, effects and much, much more. You don’t have to be an audiophile to understand – everything is clearly explained, and never gets bogged down with technical jargon.

Instead of the guitars and drums, Recording The Beatles offers a spectacularly in-depth look at the gear they recorded on. It’s a phenomenal achievement, detailing the mikes, mixers, effects and much, much more. You don’t have to be an audiophile to understand – everything is clearly explained, and never gets bogged down with technical jargon.

Steve Turner comments on how the Beatles “seemed to be breaking new ground without all the technical apparatus we have now…” That’s putting it mildly. Their magnum opus, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was recorded on two four track tape machines. Those one time state of the art decks would be considered primitive technology today, so antiquated they wouldn’t even suffice in a typical bedroom studio.

A monumental undertaking, the book boasts 540 pages, and almost as many photos. The packaging – which weighs in at eleven pounds – is outstanding; housed in a slipcase designed to resemble a 12” x 12” tape box, the hardcover book comes replete with a poster of a recording console. It’s healthy price tag – $100 – is certainly justified, and worth ever cent for those wanting to dig deeper. A significant investment for any music library, Recording the Beatles is not available at stores, the book can only be ordered from its website.

Richie Unterberger explores the vast archives of material – both music and film – that remains unreleased almost forty years after the group split up.

Richie Unterberger explores the vast archives of material – both music and film – that remains unreleased almost forty years after the group split up.

There are thousands of hours of live shows, studio outtakes, plus home demos and numerous sessions for BBC radio – a two-disc set of BBC recordings was issued years ago – but there’s enough for at least 10 cds – that have yet to see official release.

He starts at year zero: 1957 – the day that John and Paul met. Lennon was performing with the Quarrymen at St. Peter’s Church in Liverpool, and by coincidence, an amateur audiophile recorded the event. The tape languished until it was auctioned off in 1994. It’s still not on the open market, but Unterberger managed to hear snippets and reports – not surprisingly – that the fidelity is extremely low, and for all it’s historical import, it doesn’t really hold up as anything worth listening to.

He ends with the band’s demise in 1970, a year that has kept bootleggers busy for decades; there are over 100 hours of outtakes from the Get Back/Let It Be sessions alone.

The three Anthology sets that were released in 1995 and 1996 included some of these recordings, but there’s far more that in all likelihood will never be available through official channels.

Lennon & McCartney: Together Alone offers an in-depth look at each of their solo catalogues. It starts while the band were still together, with McCartney’s score to the 1966 film The Family Way, and Lennon’s Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins, the first work he did with Yoko Ono.

Lennon & McCartney: Together Alone offers an in-depth look at each of their solo catalogues. It starts while the band were still together, with McCartney’s score to the 1966 film The Family Way, and Lennon’s Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins, the first work he did with Yoko Ono.

There’s plenty of information and anecdotes for each release, and unlike the Beatles’ catalogue, as solo artists both faced critical derision, and on occasion tepid sales far from what they had enjoyed just a few years before.

All the pertinent details are included, from personnel to contemporary reviews, but an index of sidemen is sorely lacking, as are illustrations. It would have been nice to include George and Ringo’s work as well, especially considering how often the Beatles continued to appeared on each other’s albums.

Strange Brew offers a day-by-day chronicle of three of the greatest guitarists from the mid-sixties British blues scene – Eric Clapton (John Mayall/Cream/Blind Faith/Derek & the Dominoes), Peter Green (John Mayall/Fleetwood Mac) and Mick Taylor (John Mayall/Rolling Stones). Spanning 1965-1970, the book covers recording sessions, live shows, and more.

Strange Brew offers a day-by-day chronicle of three of the greatest guitarists from the mid-sixties British blues scene – Eric Clapton (John Mayall/Cream/Blind Faith/Derek & the Dominoes), Peter Green (John Mayall/Fleetwood Mac) and Mick Taylor (John Mayall/Rolling Stones). Spanning 1965-1970, the book covers recording sessions, live shows, and more.

While it was certainly never the author’s intent, the book is an inadvertent testament to the Beatles’ wide ranging influence. They could never be mistaken for a blues band, but they appear with surprising regularity throughout.

Clapton, in particular, shared a long and fruitful relationship with all four. In addition to being one of the band’s few contemporaries to appear on record with the group (‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’), he would guest on solo albums by all four.

Harrison’s friendship with Clapton continued until the end of his life. In addition to appearing on seven of George’s own albums, Harrison frequently brought him in when he produced other arists, including his production of Billy Preston’s first hit on Apple Records, ‘That’s the Way God Planned It’

There’s far more than just hard facts. Quotes from magazines and newspapers illuminate what a fast moving era it was.

All manner of curious facts are found.

Three of the Beatles were in attendance for a July 1967 party celebrating the Monkees visit to London, at which Clapton had his first psychedelic experience when Micky Dolenz gives him STP.

Harrison taking Clapton to Indian Temple in Los Angeles. In January 1966 Paul tips Clapton as the big name for the coming year.

Clapton telling an interviewer in 1970 that; “The music I want to play is rock ‘n’ roll, and blues and gospel – songs about God or Jesus Christ…songs with gospel lyrics.”

As far as the other guitarists, each has Beatle connections. George admits that the ‘Sun King’ from Abbey Road came after jamming on Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Albatross,’ a number one song at the time. The song was written by Peter Green, who would leave the group he founded a year later, explaining to a journalist “I am always concerned with what is right with God and what God would have me do, that is the most important thing to me, that dominates every thought in my head…”

© John Cody 2007