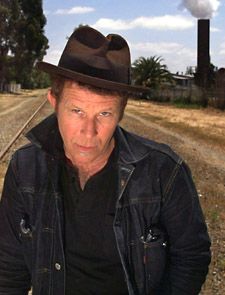

TOM WAITS has done nearly everything contrary to traditional music industrystandards.

Yet despite that, he has still managed to win a Grammy, get nominated for an Oscar, appear in more than 20 films — and most importantly, continue to release challenging music for more than 30 years. Waits describes his gravelly voice, reminiscent of Howlin’ Wolf and Captain Beefheart, as “Louis Armstrong and Ethel Merman meeting in Hell.”

This month sees the release of his latest disc, Real Gone (Anti) as well as a rare public appearance in Vancouver. Anticipation for the show was so great that the Orpheum Theatre sold out all 3,000 seats in under 10 minutes upon the box office opening.

Steve Stockman includes Waits as one of a dozen ‘secular saints’ profiled in his book, The Rock Cries Out. He writes: “Waits has spent his career raising the profile of the people who Jesus hung out with and who the Church usually has no time for.” Waits has a pastor’s care for the people he sees, writing songs to empathize in many ways with the hope of exorcising their demons.”

Demons, the devil and Jesus appear with regularity in Waits’ songs. While others performers deal with darkness in transparent attempts to shock their audience, Waits’ approach is to uncover the seamier side of life, shine a light and offer unconditional acceptance, giving his characters a grace and dignity rarely afforded them. In the process, he makes it clear there’s little qualitative difference between the tramp on the street and the outwardly successful business person.

He’s never spoken definitively regarding his beliefs, instead offering humorous, asides: “There ain’t no devil, there’s just God when he’s drunk.” Asked why he was so prolific, he responded “Well, I was raised a Catholic.” Asked whether he identified more as a poet or songwriter, he said: “I’m a Methodist.”

Waits’ songs have a strong sense of the cinematic. Francis Ford Coppola was so taken with ‘I Never Talk To Strangers,’ a duet with Bette Midler, that he hired him to write music for his film One From The Heart. Waits’ songs were nominated for an Academy Award. He’s acted in more than 20 films, including five of Coppola’s, and worked with esteemed directors Terry Gilliam, Jim Jarmusch and Robert Altman.

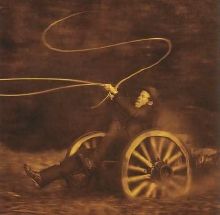

Waits’ latest album, Real Gone (Anti), is co-produced and written with his wife and long-time collaborator Kathleen Brennan (of whom Waits once said: “She’s the brains behind Pa.”) Songs like ‘Sins of my Father,’ which explores the darker inclinations passed from generation to generation, are in keeping with his longtime subject matter. Mixing primal blues, Jamaican rock-steady grooves, African and Latin rhythms, along with what Waits calls ‘cubist funk,’ it’s a stellar addition to his formidable catalogue.

His songs have been covered by Bruce Springsteen, Bette Midler, Tim Buckley, Rod Stewart and the Eagles (who prettied up his ‘Ol’ 55′ to such an extent that he commented: “The only good thing about an Eagles LP is that it keeps the dust off your turntable.”) John Hammond Jr.s’ Wicked Grin (2001), which Tom produced, consists entirely of Waits compositions save for ‘I Know I’ve Been Changed,’ a traditional gospel number that, according to Hammond, Waits insisted be included.

Johnny Cash covered ‘Down There by the Train,’ singing about the place “where the sinner can be washed in the blood of the Lamb.” The legendary gospel group The Blind Boys Of Alabama recorded two of his songs for their Spirit of the Century album in 2001. Last year Waits joined the group to sing on the title track of their album, Go Tell it On the Mountain.

Growing up in a solidly middle class home, Waits was taken with the beatnik philosophy — especially beat poet Jack Kerouac, who he described as ‘that sad, strange, solitary Catholic mystic.” Even though I was growing up in Southern California, he made a tremendous impression on me. It was 1968. I started wearing dark glasses and got myself a subscription to Down Beat.” Waits’ debut release, Closing Time (1974), took its inspiration from Raymond Chandler, Lord Buckley, Hoagy Carmichael and George Gershwin. Any boogie from Waits was of the Jelly Roll Morton variety, rather than ZZ Top. As Waits himself once claimed, for him the ’60s never existed.

For all the Bohemian interest, former girl friend Rickie Lee Jones complained that their relationship was doomed to fail, because “what Tom really wanted was to live in a little bungalow with a bunch of screaming kids and spend Saturday nights at the drive-in.” He married Kathleen Brennan in 1980, and she quickly became his collaborator. The couple’s first of three children was born in 1983. Kerouac and the beats were still inspirations, but no longer role models.

After a decade employing traditional jazz-based combos, a major change began in 1983, with Swordfishtrombones. At times chaotic, almost cacophonous — Waits has described his music since the ’80s as “sounding like a demented parade band” — his choice of instrumentation grew to include tuba, marimba, harmonium, banjo, and vocals sung through a battery-operated bullhorn. More unorthodox instruments include artillery shells and a four cubic yard metal garbage dumpster with a hole cut into one side, over which were strung seven piano strings. He describes the sound as “like trash day with a purpose.”

Remarkably, as he stretched out, sales increased. Raindogs followed two years later, and continued to make new fans. Franks Wild Years (1986) contained songs from a theatrical production of the same name that he wrote with Kathleen.

Bone Machine (1992) featured ‘Jesus Gonna Be Here,’ a straightforward gospel number about waiting on Christ’s return. He has commented that the song was inspired by preachers proselytizing on street corners in L.A. during rush hour. “It usually seemed like the most important thing that was going on but it was also disregarded by everyone .” I would always stop and listen.” In 1994, Waits performed on minimalist composer Gavin Bryars updated version of Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet, dueting on the hymn with a recording of London tramp made in the ’60s.

His 2002 release Blood Money which one writer described as containing “songs from the bottom of the world” — is based on German playwright Georg Buchner’s 1837 work Woyzeck. It delves into the nature of man and sin — and one number, ‘Misery River,’ quotes Martin Luther: “God builds a church, The devil builds a chapel.” Waits also observes: “The devil knows the Bible like the back of his hand.”

© John Cody 2004