The year was 1964. The British Invasion had hit, and overnight the Beatles had turned the entire entertainment industry upside down, leaving most American acts obsolete.

The Byrds were one of the first – and certainly most significant – responses against the Invasion. In an era where change was a constant, they had a fresh sound that combined the energy of rock ‘n’ roll with the lyrical depth of folk music, bringing a newfound maturity to the pop scene. Instead of teen anthems and simplistic love songs, they sang about social and personal politics.

A year into The Beatles’ reign the band released their debut single – ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’ It topped the charts. Later that year they hit the number one position again – this time staying for three weeks – with ‘Turn Turn Turn,’ which took it’s lyrics from the Book of Ecclesiastes. Over the next few years they would continually reinvent themselves, in the process creating three significant genres: folk-rock, psychedelia, and country-rock.

A year into The Beatles’ reign the band released their debut single – ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’ It topped the charts. Later that year they hit the number one position again – this time staying for three weeks – with ‘Turn Turn Turn,’ which took it’s lyrics from the Book of Ecclesiastes. Over the next few years they would continually reinvent themselves, in the process creating three significant genres: folk-rock, psychedelia, and country-rock.

For a season they were as big as the Beatles.

Four decades on, of the five original members – Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman, Gene Clark, Michael Clarke and David Crosby – two are dead due to various substance abuse issues, two are Christians who take their faith seriously, and the fifth, having lived a life of controversy – including jail time for guns and freebasing cocaine – has just released a new autobiography (his second) that finds him as angry as ever; at Christians, Republicans, and pretty much anyone else who doesn’t think like him.

It’s a fascinating story

I spoke at length with Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman, as well as Richie Furay and Al Perkins, who played significant roles in their lives.

The group’s first single was produced by Terry Melcher. At that point the band was untested, and only McGuinn was allowed to play on the recording. He has fond memories of the session. “I loved Terry’s production. He got really creamy things; the production on ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ is exquisite. It’s just real creamy and full. It was his idea to do it in that sort of [Beach Boy’s 1964 hit] ‘Don’t Worry Baby’ groove. And the sliding bass line was his idea.” Melcher was old school, with an ear attuned to the radio dial: “He only mixed in mono for AM radio. That was all he was interested in. He didn’t believe in stereo. He thought it was a gimmick.”

From the beginning the Byrds were regarded as one of the hippest bands in America, yet the producers they worked with – like Melcher and later Gary Usher – were known for their work with surf/hot rod acts like the Rip Chords and the Hondells – bands considered outdated and irrelevant by 1965. “I thought that Terry was an excellent producer. And Gary was, too. They both had brilliant attitudes about production. And they were very meticulous.”

The changes came fast and furious. A year after introducing folk-rock they raised the stakes with ‘Eight Miles High,’ a psychedelic classic. It was heading for the top of the charts, by all accounts destined to be their third number one until radio stations started banning the song, assuming the title was a drug reference.

Two years later – with McGuinn and Hillman the only original members left – they released 1968’s Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Adding country music to the mix was a bold move that went against the hippy ethos then in vogue, and the public wasn’t buying it. At the time their biggest flop to date, the album has grown in stature over the years, and today it’s considered a classic – ground zero for the still-thriving country-rock scene.

They even helped open the door for more spiritually-overt songs on pop radio. Their final charting single was 1970’s ‘Jesus Is Just Alright.’ The song would become a major hit for the Doobie Brothers two years later.

It wasn’t their first sacred song. The lyrics for ‘Turn, Turn, Turn’ came from the Bible. On Sweetheart of the Rodeo they covered ‘I Love the Christian Life’ and ‘I Am A Pilgrim.’

McGuinn says at the time those song’s messages didn’t resonate for him in any special way. They were just part of the band’s repertoire. “It wasn’t about songs. Songs didn’t really do it for me…I was kind of a ‘many roads up the mountain’ philosophy at that time. I didn’t discount that Jesus was a spiritual entity, but I didn’t know that he was the Lord.”

Singer Jennifer Warnes was the first person to present the claims of Christ to him in a way that made sense. “I was hanging out with her, and she had a picture of Jesus on her dresser. I said ‘what’s that?’ and she said ‘Well, he’s the only way to get through to God.’ I thought it was many roads up the mountain, that they all led to the same place, and you could be a Buddhist or a Hindu and it wouldn’t make any difference. She said ‘No, that’s not true. It’s Jesus.’ Nobody had ever explained it to me that way before. I don’t know why. Perhaps they had, and I didn’t get it. Or I didn’t want to get it…anyway, Jennifer laid it out in a way that seemed right. I was definitely in that frame of mind when I accepted the Lord.

“The Lord got my attention by allowing me to feel this horrible anxiety… I’d run into Christians and they’d pray with me. Nothing happened immediately, but eventually I was in a crisis kind of situation again with the anxiety, and I said ‘God, how can I keep from feeling this?’ And he spoke to my heart. He said ‘Well, you can accept Jesus.’ And I said, ‘Okay, I accept Jesus’ and bam, it just lifted off. It’s been gone for 29 years.”

In Hillman’s case, a fellow band member was the catalyst for change.

In 1972 he was working with Al Perkins, a legendary steel guitarist who has worked with everyone from Bob Dylan to the Rolling Stones.

“Al is almost like Johnny Appleseed. He’s saved many, many people. Some, it sticks. It’s like that parable of Christ’s with the seed; some stick and some it doesn’t take hold for awhile. Sometimes it takes hold later, as in my case.” Hillman says he “strayed a little bit, and came back a few years later.” He was baptized in 1982.

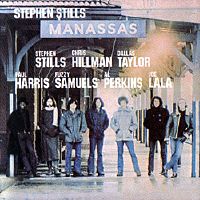

Hillman first worked with Perkins in the Flying Burrito Brothers. After that the two played together in Stephen Stills’ Manassas. When that group folded, Hillman joined the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band. Industry magnate David Geffen had scored a major payday with Crosby, Stills Nash & Young, and attempted to repeat the formula with a pre-made supergroup of Hillman, Richie Furay (Buffalo Springfield/Poco), and J.D. Souther. Hillman wanted Perkins in the group, but the idea of working with a Christian spooked Furay. Eventually he agreed, but he didn’t want to hear about Jesus.

Hillman relays the subsequent chain of events; “Initially, Richie was a little nervous. There’s your perfect example – it’s almost like foresight – the Devil was at work knowing that Richie was going to be coming over…Richie didn’t want Al because he was a Christian.”

Six months later, Furay became a Christian, and for the past two decades he’s been a Pastor with Calvary Chapel in Colorado.

When I spoke with Furay, he emphasized how important the Byrds were to his own musical journey. After touring and recording with the Au Go Go Singers – a folk group that included Stephen Stills – Furay had given up on the music business, and returned home to a job in Ohio. Soon after, his old friend Gram Parsons showed up with a copy of the Byrds’ debut album, and it changed both of their lives. Inspired, Furay quit his job, and got back together with Stephen to form Buffalo Springfield with Neil Young. When that group ended, Furay started Poco, one of the first bands to pick up on the Byrds’ country leanings. Parsons did him one better, actually joining the Byrds for their Sweetheart album, and then forming the Burritos with Chris Hillman.

The band’s importance cannot be underestimated. Richie Unterberger’s two volumes tracing the history of the folk-rock revolution – Turn Turn Turn and Eight Miles High – are named after Byrds’ songs. Documenting the entire folk-rock era, the books place the music in context, and are essential reading for anyone interested in learning more.

For those wishing to delve even further, one of the best biographies ever written on any band is Johnny Rogan’s Timeless Flight Revisited: The Sequel. This was Rogan’s third version of the book, and at over 700 pages, it’s the definitive work. Even Roger is impressed: “His first two tries had factual errors, but the third time he did it right.”

There Is A Season is Sony’s second box set summarizing the band’s career. A self-titled four-disc package was released back in 1990, but left much to be desired.

There Is A Season is Sony’s second box set summarizing the band’s career. A self-titled four-disc package was released back in 1990, but left much to be desired.

In addition to significant upgrades in sound, the new box goes back further, with a half dozen pre-Byrds recordings from 1964, including demos as the Jet Set which reveal an obvious debt to the Beatles.

The box includes a bonus DVD featuring ten television appearances filmed between 1965-1967. While the tracks are all lip-synched, their look – long hair, Beatle boots, McGuinn’s Ben Franklin glasses and Crosby resplendent in cape – was as striking as their sound.

The Byrds were legendary for their eclectic tastes. They covered everything from World War II chanteuse Vera Lynn to blues, R & B and country standards. At one point there was talk of an entire album of moog synthesizer, although only a few tracks were ever completed. ‘Eight Miles High’ was inspired by Ravi Shankar and John Coltrane, and at one point they attempted to record Miles Davis’ classic ‘Milestones.’

They were huge fans of the Beatles. Especially George Harrison. “He was the influence on me getting into the Rickenbacker 12 string” says McGuinn, “and a lot of my lead work was influenced by George’s playing.” The respect went both ways; “We did influence the Beatles and George. He wrote the song ‘If I Needed Someone’ based on my licks on ‘The Bells of Rhymney.'” In a backhanded salute, McGuinn performs the song on 2004’s Limited Edition. McGuinn also introduced the Beatles to the music of Ravi Shankar, who would become a major influence on the group, especially Harrison.

GENE CLARK

Prior to the Byrds, Gene Clark had spent a year with the New Christy Minstrels, a popular singing group that saw numerous up-and-coming talents pass through it’s ranks, including Kenny Rogers, Kim Carnes, Barry McGuire (‘Eve of Destruction’), and Larry Ramos, later of the Association.

It can be argued Clark was the most talented writer in the Byrds. With movie star looks, a haunting singing voice, and strong stage presence, he was an invaluable asset. For all the heights they would scale afterwards, something was lost when Clark left the band in 1966.

McGuinn claims there were big plans in store for Clark “Oh, he was a talented guy. In fact [Byrds manager] Jim Dickson… told me once when he was in the hospital that they were grooming Gene to be an Elvis-like solo artist when he left the Byrds.”

Sony’s original box set fell under criticism for minimizing Clark’s input. Only a handful of his songs were included, and Hillman and Crosby both voiced their displeasure. They’re far happier this time round. Hillman had no input in selecting the material, but he was interviewed for the project, and it’s clear the compilers were aware of the changes that needed to be made: “I’m extremely pleased with the new box. Sony did a great job.”

John Einarson’s Mr Tambourine Man finally gives Clark the credit he deserves. At turns inspiring and heartbreaking, for the first time his whole story is told.

John Einarson’s Mr Tambourine Man finally gives Clark the credit he deserves. At turns inspiring and heartbreaking, for the first time his whole story is told.

After extensive research – including interviews with Clark’s siblings, close friends and band members – Einarson believes he suffered from Bipolar disorder (manic depression). Family members recall severe mood swings “from euphoric highs to deep depressing lows.” Like many sufferers, Clark attempted to mitigate the extremes by self-medicating with alcohol, which, as Einarson points out, only exacerbated the behavior. “Gene always believed he could cure whatever ailed him but this was beyond his ability to deal with.” Those close to Clark agree that had he been properly diagnosed and treated he may have led a happier and longer life, but conversely, medication might have blunted his creative edge.

McGuinn agrees, stating the Clark was “obviously manic depressive…[he] had a hard time handling success. He really couldn’t do it. Whenever things started to look like they were going to get successful he’d go off and get into something self-destructive.”

Until he read Einarson’s book, Hillman never realized just how many label deals Gene had signed and then lost. In hindsight he feels Gene’s already precarious condition was intensified by showbiz excess, and that there’s a good chance he’d be alive today had he returned home to Kansas after leaving the Byrds.

In 1979 the three reunited for McGuinn, Hillman & Clark, which was a disaster for all parties. McGuinn puts the blame squarely on Clark: “Because he wouldn’t show up. For whole tours. Said he had a tooth ache or something.”

Clark died in 1991 from a bleeding ulcer, the result of years of drinking.

MICHAEL CLARKE

Drummer Michael Clarke was drafted into the band as much for his looks as talent. In fact, he had never played a drum kit before joining the Byrds. He’d spent some time playing bongos in coffee houses, but more importantly, he was a ringer for the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones. The group’s first rehearsals found Clarke banging away on cardboard boxes.

His playing improved rapidly, and after five albums with the Byrds he went on to play with the Flying Burrito Brothers and Firefall.

In the eighties he worked with Gene in Firebyrd. When they came through Vancouver the promoter was warned not to pay the band before the show was finished, not to lend them any money, and most importantly, not to let either drink before they hit the stage. For all the concerns, the shows went off without a hitch.

I spoke with Gene during the engagement, and found him to be generous with his time, and happy to answer my questions. At one point he spied Michael and brought him over to join the conversation. Each of them treated me as though I was the only Byrds fan in the house.

Michael succumbed to a life of excess – liver disease brought on by alcoholism – two years after Gene’s passing.

DAVID CROSBY

There’s always been tension between David Crosby and the rest of the group. “I don’t know where David is at. He’s right about a lot of things.” McGuinn laughs. “He was tough to work with.”

There’s always been tension between David Crosby and the rest of the group. “I don’t know where David is at. He’s right about a lot of things.” McGuinn laughs. “He was tough to work with.”

Crosby was constantly manipulating band members. Especially Gene: “He took his guitar away. He didn’t want to play bass.” Clark was a perfectly competent guitarist, but rather than have three guitarists on stage, Crosby forced him to drop the instrument.

He could be spectacularly off the mark. McGuinn says Crosby “didn’t like Dylan” and was adamant they not play any his songs, even attempting to cancel the ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ recording session. Once the record was a hit he did a quick about face, becoming Dylan’s biggest fan.

Eventually tensions boiled over, and Crosby was fired from the band in 1967. He resurfaced with Crosby, Stills and Nash soon after.

Despite ongoing requests over the past decade, McGuinn has consistently turned down all offers to reunite the band.

Hillman cares about both of them. “I love Roger dearly. I love David. But my gosh, we have to forgive each other. And we have to remember what a wonderful time we had, we shared together. In our heyday – in the Byrds – it wasn’t as bad as it is today. All of the drug use, and babies out of wedlock. It was still pretty innocent. So I look at the Byrds and what a great time I shared with these guys. And we’re still alive. And God bless the two that left. I pray for their souls. I pray that God forgives their sins, that they can find eternal rest. Because I love Mike and Gene…And I think David does. But I think that Roger is absolutely correct in that we should never work together because it can open up old wounds, so to speak. I love Roger dearly. I would love to do something with him musically at some point in time, and that’s a possibility, but if it doesn’t happen I’ll always have great memories of working with him.”

Since Then (Putnam) is Crosby’s second autobiography. It’s a confusing rant, more often than not attempting to justify questionable behavior. After a lifetime of addictions – with membership in Alcoholics Anonymous – he’s started to smoke marijuana again. Although he can no longer carry firearms – the result of numerous gun busts – he claims he needs to be armed in case religious fundamentalists take over the U.S. He’s already picked out a gun for his twelve year old son.

He saves his most vitriolic comments for the Christian Right, speculating that if Pat Robertson or Jerry Falwell ever gets into the White House, American policies will change radically: “send all the gays to New Zealand. Jews and niggers, you can have second position, be almost like citizens. Immigrant workers, undocumented aliens, noisy, smelly people of color with different gods – outta here. And women? Back to the kitchen; bear children, no matter what…”

Crosby is particularly concerned about what he sees as rampant homophobia in the church, and takes Hillman to task for criticizing his choice to impregnate Melissa Etheridge’s then girlfriend as “Archaic and mildly insane.”

To his credit, Crosby incorporates dissenting voices into the book, including Hillman and numerous recovering addicts who take him to task for his caviler attitude towards addiction.

On three different occasions I attempted to set up interviews with Crosby for this feature, and was turned down each time. I spoke with a few individuals who have worked with him recently, and one described him as ‘the most unhappy man on the planet,’ claiming he’s impossible to work with. Hillman wasn’t surprised by this assessment. “He’s still abusive. And he just had a heart attack…I mean, this man has nine lives. And you’d think, coming out of that situation in prison – and then having a liver transplant – [that] you’d be on your knees thanking God. But that didn’t happen, and that’s not for me to comment on. …I still love the guy, you know. And maybe he is unhappy. Gosh, I don’t know. I really don’t. He’s had so many chances.” McGuinn sums up his feelings succinctly, “He’s still the same guy.”

Hillman says there’s a whole other side to Crosby. “There’s a part of David that is just a pure, loving, joyful guy, and when I was sick he was there. ” Hillman struggled with a serious liver/kidney problem nine years ago. “…and through faith and prayer and some wonderful support from friends and of course some great medical care, I am now completely healed.” Crosby was one of those friends. “He was there for me… He’s helped me a few times in my life”

For all the contentious viewpoints regarding Crosby’s personal habits, one issue no one disputes is the quality of his work.

For all the contentious viewpoints regarding Crosby’s personal habits, one issue no one disputes is the quality of his work.

As he has performed in group situations throughout his career, a sampling of his best work would entail assembling material from the Byrds, Crosby, Stills & Nash – with and without Neil Young – plus duos with Graham Nash, recent work with CPR, and his handful of solo releases.

That’s exactly what Rhino Records has done with Voyage, a new triple-disc set. The first disc consists of material from 1966-1976, and finds him at the peak of his powers, when any album he was involved in would invariably end up a best seller. Disc two picks up at 1977, when his music was beginning to fall out of favor with the public. While they didn’t garner significant sales, there are many tracks well worth exploring. Disc three consists of previously unreleased material, and is the real treat here, including demos for some of his most popular compositions.

That’s exactly what Rhino Records has done with Voyage, a new triple-disc set. The first disc consists of material from 1966-1976, and finds him at the peak of his powers, when any album he was involved in would invariably end up a best seller. Disc two picks up at 1977, when his music was beginning to fall out of favor with the public. While they didn’t garner significant sales, there are many tracks well worth exploring. Disc three consists of previously unreleased material, and is the real treat here, including demos for some of his most popular compositions.

The first time Crosby ventured out on his own he produced If I Could Only Remember My Name, one of the finest albums of the early seventies. Typically, even though it’s listed as a solo album, Crosby surrounded himself with high-profile friends, including members of the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Santana, all in their prime when this was recorded. A marvelous time capsule, it’s mellow, with a loose, relaxed vibe throughout. The opening track, ‘Music Is Love,’ proclaims a sentiment – sadly – long out of fashion. Reissued by Rhino in a deluxe set including DVD Audio, this classic disc has never sounded better.

ROGER MCGUINN

Roger McGuinn brought the most experience to the band. Already a seasoned vet, he had performed as guitarist for the Limeliters and the Chad Mitchell Trio, both popular acts in the folk scene.

He’s always been drawn to traditional songs, and claims the reason so much of the Byrds music stands up today is precisely because of it’s folk roots.

Ironically, straight ahead folk groups like the Limeliters and the Mitchell Trio were relegated to the delete bins once the Byrds took off. “Oh yeah. Well, we changed rock. We rocked the folk stuff to make it work.”

Ironically, straight ahead folk groups like the Limeliters and the Mitchell Trio were relegated to the delete bins once the Byrds took off. “Oh yeah. Well, we changed rock. We rocked the folk stuff to make it work.”

More on McGuinn’s early years.

For all of the band’s success, they never really made much money. McGuinn says that outside of an initial advance that amounted to a few thousand dollars per member, the group never received royalties. He testified before Congress a few years back regarding MP3s and file sharing. Unlike the big record companies, he was all for the new technology. He describes his experience with the industry as “typical…for most people – at least in the sixties – we all got taken advantage of. Things have improved over the years; it’s not as bad as it used to be.” He’s happy to distribute the music on his own, without any label involvement. “That was sort of a dream. Who wants to be working this hard and giving the money to somebody else?”

McGuinn recently released The Folk Den Project, a four disc set comprised of one hundred traditional folk songs. The bulk of these were released through his website over the past decade, where he posts a new song every month for free downloads. As the technology has advanced considerably since starting the project, he chose to re-record most of the material in the set. One interesting curio is a recording from 1958, when he was only sixteen years old, and the folk bug had already bit. Stripped-down versions of songs he first performed with the Byrds, Judy Collins, Bobby Darin and others illustrate the passion for folk music that threads throughout his entire career.

Hillman has a deep and longstanding respect for McGuinn. “I love working with Roger. Roger’s a pro. When you get on stage or in the studio with him, he’s a professional guy. He was a joy to work with. A joy. He was the best musician in the Byrds at one time; always on the money, always creative. We all had to learn quick to get up to his level. I think in those days, he worked better as part of a team. Like most of us did. Now he’s really happy doing what he’s doing, and he’s very good at it. Very good as a solo entertainer. I couldn’t do what he’s doing. But then again, it’s different music that I like.”

McGuinn also impacted Hillman’s spiritual walk. “Roger was a big influence. I was having troubles in McGuinn, Clark & Hillman and he prayed with me one time in a taxi cab in London. Isn’t that funny? The back seat of a taxi cab, he grabbed my hand and prayed with me. Those are special times. Special things.”

CHRIS HILLMAN

Chris Hillman had recorded as a mandolin player with the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers and the Hillmen before joining the Byrds as bass guitarist. Most history books claim he was new to rock ‘n roll when he joined the band, but that’s hardly the case. Long before discovering bluegrass, he was rocking. “Oh no – I cut my teeth on early rock ‘n roll. I went through that period in 1956 until about 1960.I loved rock ‘n roll. Loved it. I lived for it.”

Chris Hillman had recorded as a mandolin player with the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers and the Hillmen before joining the Byrds as bass guitarist. Most history books claim he was new to rock ‘n roll when he joined the band, but that’s hardly the case. Long before discovering bluegrass, he was rocking. “Oh no – I cut my teeth on early rock ‘n roll. I went through that period in 1956 until about 1960.I loved rock ‘n roll. Loved it. I lived for it.”

Then he discovered folk. “[Like] Roger and David and everybody else – I got swept up in the folk music movement from 1960 until when we became the Byrds. I went into more traditional folk music; bluegrass and country and old-timey music. They were playing more commercial stuff; they were both in folk groups, and I was playing real country stuff, so somehow it worked out.”

Historically, many performers have abandoned the mainstream after finding faith, preferring to work within the Christian scene. “Most of them tend to go into Christian music when they accept the Lord.” McGuinn notes. “That’s a big business now, too. There’s very little difference as far as I can tell.” Some would go further, claiming it’s as corrupt as the mainstream. “I wasn’t going to say that” he laughs. “But… [let’s just say] I don’t know from personal experience. When I came to the Lord I prayed about it in ’77/’78. I asked the Lord what he wanted me to do with my music, and I got to stay where I was when I was called. I got to stick with the secular side of things.” But there were changes. “I had to make some choices not to do certain kinds of material. And I got the lesson not to be unequally yoked right away too, right about ’78, ’79. Not to be yoked with unbelievers.” Any chance this was Gene Clark? “Well yeah, but it was after. I was in that situation when the Lord tapped me on the shoulder about that. And I got out of that.”

From his perspective, Hillman has few problems working with non-believers.

“Well to me, that’s where I disagree with Roger. I mean, he’s right. He’s right. He’s quoting Second Corinthians. Paul is saying that. But then I look at it as Al [Perkins] has, [that] there’s a possibility – and I used to have this problem when I was firmly entrenched in the Evangelical Church – I had people come up to me [saying] ‘How can you play in night clubs, bah dah dah.’ And I said ‘well, there’s just a possibility that I can change someone’s life, by example.’ So there’s where I disagree with Roger on one point. He won’t work with David Crosby. I still love David. I mean, love the sinner, hate the sin… I love David. [But] I don’t think I could work with him, either. He’s got a mouth on him like a Hong Kong sailor, and it’s not comfortable. But he respects me. He had written something about Christian fanatics and [George] Bush and all this, and I wrote him back saying ‘I’m a Christian fanatic – come on!’ And he said ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t mean you – I respect your beliefs.’ And I talk to David. Probably more than I talk to Roger.

“I work with a couple of guys who grew up in the Catholic Church in the fifties. Herb Pedersen and Bill Bryson. They were altar boys. Pre-Vatican II. And Herb still has it in his heart. He is really a believing Christian, but he can’t go back to the Catholic Church. It just drove it out of him. My point is, the more I’m around him, the more he’s coming over. Ever so subtly, I am bringing him back. And he has actually gone to a liturgy with me. We went into Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in New York two weeks ago, and he dipped at the holy water, and he was crossing himself – I watched his face and it was right back there. It meant something to him. And whether he goes back to the Catholic church or whether he goes to a Methodist church – whatever – it’s just that he actively [attends].”

“My point being, I can work with people that aren’t believers, and maybe I can change their life. I’m not going to proselytize and get in their face with it, but, by example, I can change lives. And the album I just recorded is really a gospel album. And hopefully it’s not an in-your-face ‘Christian’ record. It’s not like one of Richie’s [Furay] albums, which are very, very Christian – and very good. But I choose to take more of a low key approach to that.”

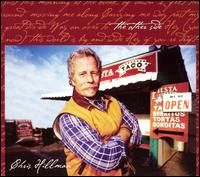

Hillman describes The Other Side as “songs to soothe and uplift the soul.” It’s mostly bluegrass, the bulk made up of original gospel material. He revisits a few songs from his vast catalogue, including ‘Missing You’ and ‘True Love’ from the Desert Rose Band and ‘It Doesn’t Matter’ which he wrote with Stephen Stills for Manassas. ‘Eight Miles High’ – a standout performance – is recast as a straight ahead country tune. From start to finish, the album is a delight, and it’s obvious – like McGuinn’s latest work – that Hillman is doing exactly what he wants, rather than following record company formulas for selling units.

Hillman feels a burden for former band mates like Crosby and Stephen Stills. “Those guys are firmly entrenched in their own religion, which is secular humanism. That’s what they believe in.” When Al Perkins was working in Manassas, Stephen told him ‘Well, I talked to the priest, and he says I’m okay.’ Hillman laughs. ‘That’s not really how it works.” But he has many positive things to say about each of them.

Hillman feels a burden for former band mates like Crosby and Stephen Stills. “Those guys are firmly entrenched in their own religion, which is secular humanism. That’s what they believe in.” When Al Perkins was working in Manassas, Stephen told him ‘Well, I talked to the priest, and he says I’m okay.’ Hillman laughs. ‘That’s not really how it works.” But he has many positive things to say about each of them.

“Stephen Stills helped me. And he’s certainly not a believer. And so has David. And that’s how you measure a man. You’ve got to measure a man by: ‘can I rely on this man if I’m in trouble.'”

Stills was recently quoted regarding his overbearing personality, and claims it’s an attempt to hide an inherent shyness. Hillman is impressed. “That’s pretty revealing of him to say that. You know, I love the guy. I mean, seriously, I really, really love him, and I think he’s one of the most underrated artists out there. He’s just a phenomenally gifted guy. I would do anything in the world to be able to get him out of that quagmire that he lives in, of substance abuse and negativity and all that. I would give up anything to be able to do that, to turn him around. Could you imagine a completely sober, healthy, clean, guy? The kind of music he would do?”

Hillman was unaware that Stills is claiming he’s been sober for the last couple of years; ‘Well that’s great. I hope he is. I shouldn’t say anything, because I don’t know. I haven’t talked with him in so many years, but he was very, very kind, and generous with me, and I learned a lot of music from him, and he was always there when I needed help.”

He has fond memories of working together with Stills in Manassas. “You know that first album was really terrific. I thought the band was great. I know Al had a great time in it. [Al shares his feelings and told me he hopes the band will one day reunite]. That band was pretty darned good on stage every night. Of all the bands – I can’t put it up against Desert Rose – but that was my favorite. Manassas was a darned good band. We could do anything from straight traditional bluegrass and country to a salsa number. I was way over my head in that band playing guitar. I would have probably been more comfortable on the bass, but I don’t know if I would have been good enough to play bass in that thing. But it was a great band.”

After a lifetime spent in the performing, Hillman understands the darker side of the industry. “You know, the music business is Satan’s playground… it’s all about the ego; it’s me, me, me. And it’s worse nowadays…” He recounts taking a tape that described a sexual act in detail away from his daughter a few years back; “The Byrds, the Beatles, even the Rolling Stones didn’t do that…I mean, we loved to play music. That’s the gift of God. And we get to play; we get to sing, and all these things. But there are people around that just want to drag you into the pit…I think there’s some pretty tough things that go on… There’s nothing of substance in it.”

McGuinn agrees, but with a qualification. “Well, it’s about money. Yeah, I’d say there was a definite satanic influence on the music business, but you could find that in any business. So you kind of just stay on the sunny side of the street.”

Hillman is a student of history, and believes the US tearing itself down from the inside. He has some fascinating, theories.

He posits that 1968 is when it all began to go wrong. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy – who the Byrds had worked with during his presidential campaign – were both assassinated. The Chicago Democrat Convention erupted into violence, as police beat citizens on camera. And hard drugs came on the scene.

McGuinn: “And Altamont [actually 1969]. Right before that was kind of soft stuff.” But he doesn’t pinpoint it to a year. “I wouldn’t be that specific about it. I think the sixties in general, everything was escalating in a kind of hedonistic direction, and the hip scene, the hipsters, people who had experimented with drugs, they were into heroin and mescaline and peyote and cocaine. Anything you could get your hands on, basically. They didn’t just draw the line at pot. There was a lot of drug abuse going on in the hip scene. And then that gradually became mainstream, where everybody was touched by it, at least to some extent. It was just like a general corruption, a mass corruption of morality.” Without even knowing it at the time. “It was kind of like the frog in the water, where the temperature comes up gradually.”

Things went from bad to worse. “It was just rife with temptation and negativity.” Hillman laments. “Gosh, I lost a lot of people then, in that decade of the seventies.

“I had accepted Christ with Al, and then had turned my back. In Souther- Hillman-Furay I was getting into mischief that whole decade. Pretty down and out; just bad stuff, you know. By the grace of God, God had different plans for me.

“[But] Al was a big factor in my life. I’ll tell you one thing: if ever there was a strong man – sometimes to his own detriment – it’s Al Perkins. Here he is, a lone, tiny part of this huge thing which is not [receptive to the gospel]… he’s holding on, he’s holding on to his faith through this tumultuous, just negative lifestyle we were all involved in. But sometimes Al, as much as I love him, can be unbendable, and I had to use that analogy with him once. I said ‘Al, just like the oak tree, it has to bend in the wind. You have to give sometimes in dealing with people and stuff…'”

Today Perkins admits that while he never indulged in any of the traditional rock ‘n’ roll vices, he was guilty of the sin of pride. He was so proud of his faith, that it cost him a couple of marriages. “He’s had some…not the most successful unions. Yeah. I’m sure it is [his pride].

On the subject of pride, Hillman mentions the book Father Joe: How I Found My Faith.

“What did Father Joe say? Everything was down to selfishness. He would never judge or condemn the man’s role in that book. But it was always ‘you’re selfish.’ And that’s what it is. And pride is selfishness, drug abuse is selfishness – it’s a disease of selfishness. It’s me. And we are following in the footsteps of Jesus to not be that way. To give. To help.

“I get bent out of shape with rock star benefits. Just send a check. You don’t need a pat on the back. Charity is not to be rewarded. Charity is to be anonymous.” He’s put off by high-profile celebrity benefits. “It’s very superficial. Actually, we were sort of chuckling; the Chicago Tribune had done an expose on Farm Aid. I remember turning down Farm Aid in the nineties when they were starting. I had said ‘can you show me more about the organization? Are you helping people with their mortgages, or foreclosures?’ And I never got an answer. Then something came up and I couldn’t do it, and they just gave me the cold shoulder in Nashville for awhile. And finally it ends up with them doing an expose on Farm Aid in 2005, and it really was a lobbying group, and it never did help any of the farmers. It cost so much darn money that they never netted any money. The money they netted went to a lobbying group.”

DENOMINATIONAL DIFFERENCES

“When I was first a Christian I didn’t put too much credence in the Garden of Eden and Genesis. Then I realized as I got older that there really is validity to man the fallen species. Whereas Christ came to save us, we are determined – even as Christians – to throw a monkey wrench into something as beautiful, as perfect, as simple as the concept of forgiveness and love that Christ preached in Christianity. We’re determined to throw a monkey wrench into that as a species. Even as Christians. So hence, in every church, or synagogue even, there’s always infighting with the members of the church body or synagogue body. It never fails. You think your church is the only one that has these problems with people? You’re looking at why is he doing this? It’s just our species. It’s just our fate to aspire to get above that. And the devils’ main purpose is to make you quit the church.

“I don’t have a lot of tolerance for people that say ‘it’s in my heart’ but don’t participate. Yes, I’m being judgmental, but if you’re going to swim in the water, then jump into the water. Which means go to a church, worship with other people. There’s a special thing when the Holy Spirit can come into that church when you’re with the body of Christ, you’re in that church with other people.

OTHER PATHS

Hillman grew up without much of a church presence in his family.

Today, his sister is a minister in the Unitarian Church. They fought at their mother’s funeral. “Mom had requested ‘Turn, Turn, Turn’ be sung at the service, but my sister wanted to play a new-age song. She’s a minister in the Church of Religious Science…I love her dearly, but to me, that’s a cult. First of all, it’s an oxymoron. Religious science is an oxymoron. Religious: faith. Science: analyzation. Proof. It’s not really a church of Christ. They don’t follow Jesus. She says, ‘We follow all the great prophets.’ I say, ‘Uh-huh. Do you?’ So basically they can sort of do whatever they want as long as they don’t hurt anybody. I’m going, ‘That doesn’t quite work out for me…’ So” – he begins to laugh – ” we don’t have [these] discussions. On the other hand, she’s done amazing hospice work with people who are dying, and she devotes her time helping people, terminally ill and stuff. So there is some good there. But…those things are funny. That’s the religion of convenience – it’s convenient. I call it Reader’s Digest metaphysics. It just doesn’t have any substance to it.”

In the sixties McGuinn became involved with a philosophical group that he still can’t figure out. “I used to be in this Eastern thing called Subud… I changed my name to Roger. I still have no idea what Subud is. It’s kind of a spiritual thing, but I couldn’t put my finger on what it is. I know it’s not Christianity…it was a spiritual exercise. That’s all I can say. It didn’t have any doctrine.”

Subud policy includes adherents receiving new first names. McGuinn – who was Jim at the time – was instructed to pick a name beginning with the letter ‘R.’ He had many choices before Roger, all with an aeronautic theme. “Rocket, Retro, React.” He laughs “…space names.” But the powers that be felt Roger would be most appropriate. I mentioned my newborn son is named Jett, and he’s impressed “That’s a cool name. I like that name.”

George Harrison maintained that nothing matters except knowing God, and that all paths lead to God. “Well, he was stubborn about it. We did try to tell him about Jesus and he didn’t want to know. He didn’t like that.”

In 1986 McGuinn was touring Europe with Bob Dylan and Tom Petty. “…we went to Friar Park [George’s home] and hung out. And George came to a couple of concerts we did in England. We all went out to dinner, and Joan Taylor – [ex-Beatle and Byrds press agent] Derek Taylor’s wife – and I [spoke] to George about Jesus, and he didn’t want to get into it. He was still stubborn about the many roads thing or the Maharishi, or I don’t know what exactly he was into, but he didn’t want Jesus.” Would it be an out-and-out rejection of Jesus, or just saying ‘well, if that works for you…’ “I think it’s more a rejection of Jesus.” That’s tough to square; someone who claims ‘God is everything,’ yet rejects Christ. “I know. That happens a lot in the world…”

CATHOLIC CHURCH

McGuinn was raised Catholic. “Well, my father was Catholic and my mother was Lutheran…” He begins to laugh. “so the nuns used to say ‘he’s not really a Catholic.’ There was not a very ecumenical spirit in the Catholic Church at the time. I went to mass every morning, and I took communion. I really felt close to the Lord when I was about twelve years old. Whenever my first communion was – but I felt real close to the Lord at that time. And I used to feel great coming out of confession.” Besides the fond memories, I wondered if there was a negative side as well, as some former Catholics have claimed. “Well I had that too, where they would hit me, and so on. There was a lot of slapping going on.” He laughs. “But I just had a lot of God, and I could feel the Lord in my life. So He was there, from early on. I had that…but I went away and I became agnostic, and then I did this Eastern searching stuff And in 1977 I opened my heart to Jesus…”

Hillman attended a Baccalaureate Mass as part of his daughter’s graduation from a Catholic University. “These girls come out dancing with white gowns on and it looked like something out of an ancient Athenian temple pageant to Zeus. I’m not kidding. And they do the Eucharist – they do the communion in the middle of the room now. I guess they don’t have an altar. So I asked a Catholic woman I know who’s a good friend of mine and she said, ‘Oh, that’s called liturgical dancing on special holidays.’ What!?” He starts to laugh. “I didn’t say a word.

“The old things about the Catholic Church, the Latin Mass, [with] a little more mystery to it, and the sacraments, are gone now. And it’s been replaced by ‘everybody can have a good time, you can come to any mass you want, wear whatever you want, we’re going to have the rock band mass.’ So I’m looking at it like, okay, they’re changing to bring in more people, and that’s not the way it is…to me. I have a problem with that. It doesn’t mean anything to me. I want to hear the liturgy done at any Orthodox church where it has not changed for 1500 years. It’s the same liturgy whether you’re in Zambia and they’re doing it in Swahili, or you’re in the middle of Athens and it’s in Greek. It’s still the same liturgy. It has not changed one iota. And the sacraments are special. This is the Church of Christ. This is the church the way it began. And then when Rome split from the church, the Filioque, where they wanted the Holy Spirit to emanate from the Father and the Son, and the Orthodox were going ‘no, the Holy Spirit comes from the Father.’ Anyway, whatever. I can’t get into comparing religions. I really can’t. I can’t be judging or pointing my finger, and saying ‘my way is the right way – yours is wrong.’ I can’t do that. Whatever’s comfortable for the individual.

“I’m comfortable where I am, and I wasn’t as comfortable when I was an Evangelical, but I have nothing against that. I had some beautiful moments then, too.”

He’s disturbed by an anti-Catholic bias he observed during his time in the Evangelical Church. “There were many, many, many Evangelicals that were very judgmental of the Catholic faith…That’s back to man the fallen species, throwing a monkey wrench into one of the most perfect concepts ever given to us, to follow. And we somehow manage to goof it up every time. It’s the Devil working.”

GREEK ORTHODOX

Hillman eventually left the Evangelical church.

“My wife is Greek, and grew up in the Orthodox faith. The children were baptized [in that church] – and I was fine with that. But I was an Evangelical before the children were born, and she was going to church with me. And then I started to question it. It wasn’t fulfilling what I was looking for – being as diplomatic as possible – I wasn’t getting the fulfillment out of it. And I got curious about the Orthodox faith. My wife did nothing.” He laughs. “All she did was tell me ‘Oh, I’ve been praying for you for years.’

“I started to ask questions, and then I took classes from the priest that the kids and my wife went to. And I learned. I said, ‘why do you have icons?’ Because that’s the first thing a lot of Protestants [think]: ‘Well, they worship pictures, they worship statues. ‘ And the priest says ‘open your wallet.’ I pull my wallet out. He says ‘what’s that, you’ve got pictures of your family?’ I said ‘yeah,’ he says ‘why?’ I said, ‘so I can always remember them, and I always keep them in my mind.’ He said ‘we venerate the icons to remember, to remember the martyrs who died holding onto their faith. That’s why we have Icons.

“We venerate the Virgin Mary – the Theotokos as they say in Greek. Maybe not quite to the extent that the Catholics do, but we do acknowledge her as a very sacred person. As the mother of God, as the women who was chosen to bear Christ.

He’s anxious to clear up misconceptions, of which there are many; “Here’s another myth that I’m going to dispel – they don’t study the bible. Yes we do. We have daily bible lessons. Daily. We also have bible classes on a weekly basis. I haven’t been in a while, but the daily Bible readings I do every day.

“And I believe in confession – it’s not the old Catholic thing of getting in a little booth. When you have confession with a priest, you sit down with him, and the priest looks at you and says ‘I’m not listening to what you’re saying. I have no say in this. I’m just a conduit to God. And you talk it out, and then he prays over you. You say ‘Father, I da-da-da. And he says, ‘uh-huh.’ You’re confessing your sins, usually every Easter – but you can do it as much as you want.

“I firmly believe in all of the sacraments of the Church. I just think that’s something that may be missing in the Protestant church – although some Protestant churches are now taking communion. A couple times a year or something. We do it every Sunday; it’s still wine and bread as it was at the Last Supper. And as we break the body of Christ, it’s a real special time. It’s just very, very special.”

What I feel in the Orthodox Church, what I experience, is the living Christ. I experience that by having the sacraments. It creates an atmosphere during a Sunday service, or a liturgy, as we call it. I really feel a very strong presence of the Holy Spirit when I’m in a liturgy.”

FAMILY

Becoming a father was a major change for Hillman. “You grow up real quick. Once you make that decision to have children, you have to be aware of one thing; selfishness is out the window. Your priorities change and it is not about you anymore. It’s about them for the rest of your life. Whether they’re married with children, out of the house, you’re still going to have them and be worried about them. So your priorities change.”

He couldn’t do it without his faith. “When I see a child in the newspaper or in the news a child’s been killed or died, and I wonder, how do these families cope with that loss without a strong foundation, a Christian/Judeo foundation. How do you cope with that? You have to believe in something. There’s not a day goes by that I don’t pray for my children.”

It took awhile to get his priorities straight. “Oh, I had a couple of marriages that weren’t very good. That was when I wasn’t quite grown up yet. But Connie my wife was a blessing, an angel sent down to save me, I think.

“I only regret that I didn’t have four more. I have two. Two blessings. Yeah, my son’s a handful, he’s 16 years old, he’s a football player and he’s got a mouth on him. But he goes and serves in the altar, he makes good choices, he’s a good student. He’s a typical boy, but he thinks about things when he’s tempted.”

I asked if he sees himself in his son. “I think he’s a better version, way better. I had a lot of heartaches when I was growing up. I had a great childhood till my dad died when I was 16 and then we were destitute. But that’s okay, it built some character. I think it helped me. We all have that, we all have some sort of situation we have to overcome, so onward we go.”

His daughter is currently going for her Masters. Before that she attended a Catholic Jesuit University in Los Angeles. “And got a great education, I must say. But just because it was a Catholic University did not mean it didn’t have a lot of ultra-leftist liberal professors that I was pulling my hair out about.”

And did she share her father’s sense of frustration? “She was in the Young Republicans Club on campus. [There were only] three or four members!” He laughs. “She got so angry with some of these guys. She was an English major – and she had this professor; older guy, ponytail, sort of my age. And they were to give an interpretation of a poem, and my daughter likened it to the crucifixion. And rather than grade her on her writing ability, he marked her with a C-. With big red letters he wrote ‘Not everyone feels the same way as you do.’ And I’m going ‘this is a Catholic university?’ And he is exerting his atheism. He was offended, and you know how people react: ‘All Christians are fanatical crazy people.’ As I said earlier it’s that anti-Christian bias. It permeates most of the universities in this country… And your country!” He’s not impressed with Canada’s recently enacted gay marriage laws. “My God, talk about secular humanism gone to the extremes. And we’re heading that way too.”

MCGUINN’S EARLY YEARS

McGuinn recalls the folk-era fondly. “It was fun. Looking back on it, I still like the music. It’s wonderful music. [As far as] the politics of the folk scene, I really never got into that. I just liked it for the music. I kinda separated out the politics.”

He got his education as the legendary Gate Of Horn folk club in Chicago. “It was very healthy. Very robust. It was going every night of the week. It was always full. Everybody was enthusiastic about the artists, Odetta, Peter Yarrow would come in, Judy Collins, Bob Gibson and Bob Camp.”

McGuinn’s first exposure to folk music was when Bob Gibson performed for his high school class in 1957. Immediately taken with the music, he enrolled in Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music the same year.

Gibson was the centre of the scene, yet is pretty much forgotten today. “He was very influential. Unfortunately he never got a hit under his own name. He kinda missed the boat on the whole Peter Paul and Mary and Bob Dylan rise to success. Although in my opinion he inspired all of them. The [Mitchell] Trio were inspired by him. Definitely the Limeliters. When I went with the Limeliters most of their repertoire was Gibson arrangements.” Gibson recorded At the Gate of Horn with Hamilton Camp – formerly Bob Camp, another Subud practitioner. The album should have made them stars, but little came of it. “I thought it was excellent work. The harmonies were so dynamic, and their energy was way up there. It was really great stuff.”

Gibson never had a hit on his own. “Well, maybe [because of] his lifestyle. He was kind of a party guy, and he never paid attention to business. It might have been a combination of things. He actually did work with [Albert] Grossman at one point.” Grossman was a legendary manager who handled Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul & Mary, Janis Joplin and numerous other high-powered acts. “Grossman put Gibson and Camp together, and was trying to get him and Camp to be a Peter, Paul & Mary kind of thing, which they probably would have been the Peter Paul & Mary if it had worked out, but Gibson didn’t want to do it.”

One of the most popular acts of the era was the Kingston Trio. “The Kingston Trio were somewhat of an influence. Dave [Guard] was influenced by Pete Seeger. I would say that Pete was the influence on him. And me. I liked the Kingston Trio. I thought they were good. I actually auditioned for the Kingston Trio before John Stewart. I was up in Marin County, hanging out. It was after the Limeliters, before the Chad Mitchell Trio. And I met the Gateway Singers. I’d met them at the Hungry i, and one of the guys in the Gateway Singers had an uncle who had a house in San Rafael. And the uncle was in Europe for a while, so we all stayed there, we kind of used it as a crash pad. And while we were there Nick Reynolds came over in his red Ferrari and picked me up and took me over to Bob Shane’s house where Bob had set up a tape recorder and a Neimann mike and he was auditioning people. And I auditioned for them but I wasn’t quite developed enough at that point for them.”

Near the end of his tenure with the Mitchell Trio, McGuinn was approached about playing with the New Christy Minstrels. He considered the offer, even going so far as to attend a photo session with the group – a shot that appeared on the cover of TV Guide – but never performed with them.

BOBBY DARIN

Instead, he accepted an offer from former teen idol Bobby Darin. Initially the job entailed accompanying Darin onstage during a folk segment of the live show, but they were soon writing together in New York City. “It was a brief experience working for Bobby and the Brill Building. I really didn’t enjoy it. It was a day job. I had to show up at nine o’clock in the morning and work ’til five. It was like a little cubicle. You get there in the morning and then you have a half hour lunch break and Bobby would buy everybody cheeseburgers and Dr. Brown’s cream soda from the deli downstairs and you’re back to work. And it was a grind. It paid $35 a week.” But it provided invaluable training for understanding the music industry. “Oh, great education. And that was why I did it. But it wasn’t something I enjoyed doing.”

One of the songs that came out of this arrangement was ‘Beach Ball,’ which they recorded as the City Surfers; “It was Bobby Darin, Frank Gari and me. That’s all. Just the three of us. Bobby played drums, Frank was a keyboard guy, and I played guitars. And we all sang and clapped our hands and shouted a lot.”

It was never a hit. “Not our version of it. But it did get to the top ten in Australia.” The song was covered by Jimmy Hannan – a popular Australian TV star at the time, and reached #4 on the charts there in early 1964. The recording featured the Bee Gees on background vocals, and was later released in America on Atlantic records, making it the first ever U.S. release to feature their voices.

In addition to Darin, McGuinn recorded and arranged for Judy Collins on her 1963 effort, #3, which includes a take on ‘Turn, Turn, Turn’ two years before the Byrds rocked it up.

Dion was the first industry insider to understand what McGuinn was trying to do. In 1964 McGuinn auditioned for the doo-wop legend, who was knocked out by his the folk and Beatles hybrid. Rather than hire him as a sideman, he told McGuinn he was on to something big, and encouraged him to pursue the new sound.

Back to main article.

© John Cody 2006