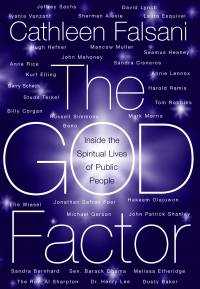

Cathleen Falsani, The God Factor, Sarah Crichton Books

As religion reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times, writer Cathleen Falsani explores the spiritual lives of politicians, authors, coaches, musicians and others who impact our culture. She’s enjoyed fascinating conversations with celebrities not always known for their beliefs, discussing exactly what it is they believe and how it informs their lives and work.

As religion reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times, writer Cathleen Falsani explores the spiritual lives of politicians, authors, coaches, musicians and others who impact our culture. She’s enjoyed fascinating conversations with celebrities not always known for their beliefs, discussing exactly what it is they believe and how it informs their lives and work.

She’s not a seeker in the traditional sense. “I’m a Christian. I’m not particularly good at it, but that’s where my faith firmly lies.” Believing that all truth is God’s truth, Falsani felt that she could learn from each interview, and that it could only serve to enrich her own faith.

The God Factor includes thirty two profiles, twelve of which first appeared in the newspaper, most in different form, expanded and rewritten for the book.

I talked with Falsani last month.

The book’s concept first took shape in 2002, when she accompanied Bono during his tour of Midwest churches representing DATA, an organization dedicated to promoting AIDS relief, eradicating debt and abolishing unfair trade rules in Africa. The two spoke at length, and her dispatches were carried on the front page of the Sun-Times every day for a week.

“It was amazing, the coverage that the paper gave to it, and readers responded viscerally either loving it or hating it. Agreeing with him or trying to toss him out of the tab, as it were. I fully enjoyed that, and I love having these conversations with people no matter who they are. Famous or not. This is the kind of conversation I like to have. The book isn’t trying to say that these folks have anything more important to say because they’re famous. That wasn’t the intent. But these people have shaped our culture in a way that most average folks haven’t, so I thought that was important, to ask them to share how faith does or doesn’t play a role in their life.”

Typically, Bono had much on his mind, especially regarding issues of faith; “I don’t set myself up to be any kind of Christian. I can’t live up to that. It’s something I aspire to, but I don’t feel comfortable with that badge. It’s a badge I want to wear. But I’m not a very good advertisement for God.”

Years of watching Christians getting it wrong – being overly-judgmental and self-righteously attacking each other – has caused Bono’s own spiritual life to resemble an obstacle course; ”where I’m trying to dodge what you might think are weird and wonderful people who are sometimes dangerous. Dangerous in the sense that spiritual abuse is rather like any kind of physical or sexual abuse. It brings you to a place where you can’t face the subject ever again. It’s rare for the sexually abused to ever enjoy sex. So, too, people who are spiritually abused can rarely approach the subject of religion with fresh faith.”

He discusses his great admiration for Billy Graham, who he refers to as his hero. Years ago Billy had asked to meet with the band in order to give them his blessing. At the time they were in the middle of a lengthy tour, but Bono flew immediately to Graham’s home – “flew there right away in case he might forget.”

Bono was the perfect subject for her initial columns – there’s a personal connection for Falsani that goes way back. As a youngster she assumed the world and the church could never co-exist peacefully. You were in one camp or the other. Hearing the band’s sophomore album October opened up a whole new reality, a world of possibilities that said you could love God with all your heart and still be in the world. In fact, impact the world. "I was absolutely transfixed by the extraordinary mix of faith with rock ‘n’ roll – a forbidden fruit at our house." She credits the band and that album in particular with inspiring her to pursue degrees in journalism and theology, setting her "on a course that continues today: to discover God in the places some people say God isn’t supposed to be. To look for the truly sacred in the supposedly profane."

FROM THIS TO THAT

A variety of outlooks are represented. From Choreographer Mark Morris, an avowed atheist; “I detest and despise pretty much every branch of Christianity,” to Michael Gerson, who Time magazine listed as one of the ten most influential Evangelicals in America last year.

As speechwriter and policy advisor for George Bush, Gerson often incorporates Bible verses into the President’s speeches. He argues that faith is vital to the nation’s history and future, and that it transcends political party affiliation. Gerson attended Wheaton College – also Falsani’s alma matter – an Evangelical school dedicated to blending faith and reason in all disciplines.

For the most part Falsani avoided religious leaders. Traditional Jews, including Dr. Elie Wiesel (“an extraordinary human being”) and conservative Christians like Gerson were included, but anyone that made their living through ministry was left off the list. “We purposely did not want to include people who are known primarily for being religious leaders. To ask religious leaders these questions would have been a very different kind of book.” For one, regardless of which side you’re on, things tend to become confrontational: “We’re playing a tug of war with – well, at the end of the day with Jesus mostly. With morality, who gets to define what it means. That’s part of why I wrote the book. Because I just felt like the dialogue such as it was in the public square in the U.S. was mostly a couple of big bellicose voices talking. With very polarized ideas, a lot of them from one particular point of view. And I thought, ‘what could it hurt?’ As I understand the world to be, the more we talk the more we might learn about each other. And knowledge can only make us free from fear.”

There were surprises.

Like Playboy magazine founder Hugh Hefner. His parents were religious; “Prohibitionist, Puritan in a very real sense.” In addition to avoiding the more obvious temptations like drinking and smoking, they shunned all form of physical affection. “Never hugged. Oh, no. There was absolutely no hugging or kissing in my family.” He readily admits that this may account for his outspoken opinions around the hypocrisy of espousing family values while not living the same.

He follows a personal moral code, and claims he was “saved a long time ago,” but doesn’t believe in the biblical God; “I believe in the creation, and therefore I believe there has to be a creator of some kind, and that is my God.”

He learned morality from his parents. And from the movies. He cites director Frank Capra (It’s a Wonderful Life/Mr. Smith Goes to Washington) for his portrayal of the American dream: democracy, personal and political freedom, and “a right to live your life on your own terms as long as it doesn’t hurt anybody.”

For Hefner, watching film is a spiritual experience. Much to his surprise, Falsani readily agrees. Delighted to have “someone like you dealing with the subject of religion,” the two connect through a shared love of film. Falsani recalls; “It was trying to find that common ground. Having God be the go-between God, no matter where he wants to take it.”

It was genuine and heartfelt. “I love movies…it’s probably the most easily transcendent vehicle…” She mentions HBO’s Six Feet Under, and the current season of The Sopranos as examples of the power of story; “ I love The Sopranos. (It’s)one of the most articulate, difficult, lovingly done and well thought out bits of theological commentary that I’ve seen in a long time.” Not that she sticks with one genre. “I love film. All kinds. I find just as much value in Jim Carey’s Bruce Almighty. I’m not a snob.”

HAKEEM

Falsani makes it easy to understand those whose faiths fall outside the traditional North American mainstream. Former basketball great Hakeem Olajuwon – whom she describes him as “a most gracious man – a really lovely human being,” explains his beliefs as a follower of Islam in a straightforward manner that takes the mystery out of what – while the second largest religion in the world – is frequently misunderstood in America. Olajuwon was raised in a Muslim country as a Muslim, but fell away, before returning to the faith years later.

BILLY CORGAN

Smashing Pumpkins’ leader Billy Corgan talks about his generation’s search for God, and his hope to point them in the right direction. He searched for years on his own, self-absorbed and depressed. At the peak of his career he felt empty inside; “…it sucked because it had no foundational meaning beyond what I thought and did.”

He claims people today are so self-possessed they can’t even identify the emptiness for what it is – a spiritual hunger; “They’re looking for God, but you can’t tell somebody who is individuating that what they’re looking for is God.”

He agrees his older lyrics could be negative, but claims that was simply a reflection of his generation. The music he produces today may have lost some of it’s aggression, but he’s as adamant as ever; “the message hasn’t changed at all. How I’m doing it has. I’m not punching the listeners in the head anymore.”

JEFFREY SACHS

Economist Jeffrey Sachs is not a believer, but he takes inspiration from various faith traditions, citing the Catholic Church’s emphasis on the preferential option for the poor.

Rather than citing any sort of spiritual incentive, he offers a pragmatic motive for helping others; “There is a very good reason to help the poor: You may be poor yourself [one day].” Sachs has worked closely with Bono on the Drop The Debt campaign, and believes we can see an end extreme poverty by 2025. He argues that while eight million die each year simply because they are too poor to survive, our generation could choose to end poverty.

LEFT CHURCH

Many who grew up within the traditional church left at the first opportunity.

Aboriginal writer Sherman Alexie (Smoke Signals) was horrified when the churches on his reservation united en masse for a book burning: “…I loved books. I loved music. And they were burning Pat Benatar! What the hell’s wrong with you! You’re burning Pat Benatar! I grabbed my books and ran home and thought, That’s it. I wasn’t exactly an atheist, but I certainly wasn’t going to buy into a God that allowed that to happen.”

ANNE RICE

Best selling horror/fantasy novelist Anne Rice tells of an almost forty year period she lived as a “fashionable atheist.” God was watching over her through it all, she feels today. She returned to the Catholic faith of her youth in her 1998. After writing a series of books on vampires and – under pen names – erotica, she recently published Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt. The first of a trilogy that will chronicle the life of Jesus, the book was directly inspired by her faith. Beliefnet.com named it the best spiritual book of 2005.

ETHERIDGE

When I asked Falsani about some of her favorite interviews, she mentioned Melissa Etheridge; “She is one of the most gracious people I’ve ever spent time with. When I interviewed her it was a month before she was diagnosed with cancer. She felt that she’d never been in a better place in her life, spiritually, emotionally, with her family…‘spiritual not religious’ would be the category to put her into. She kind of gleans from a lot of different things. (She) was one of those people who said to me ‘I love talking about this. No one ever asks me. Every once in a while an interviewer will ask are you religious and I’ll say no I’m spiritual, and that’s as far as it will go.’ I could have sat there all day with her. She was incredibly candid. I had to keep on reminding her that she had other interviews after mine.”

Ethridge was heavily involved in Christian youth groups while growing up, at one point even writing a musical about Jesus. At nineteen her mother threw her out of the family home after learning her daughter was gay. Deeply confused, Melissa confided in the chaplain, who had a gay brother. He refused to condemn her, saying he didn’t believe God would create a love that was wrong. “It was the kind words of one religious chaplain that…kept me from being a complete atheist”

MAHONEY

Actor John Mahoney was the source of her favorite chapter in the book, “I loved spending time with John. He’s just a delightful human being.” Best known for his work on Frazier, he’s a Tony award winner, and member of the Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company. In the face of personal obstacles – disappointment at never marrying, and a bout with cancer – he remains thankful, and takes great joy to be working in his chosen field. There’s a deep humility, yet he’s straight to the point regarding his beliefs: “…Christianity is probably the most important facet of my life.”

TOM ROBBINS

Author Tom Robbins (Even Cowgirls Get the Blues) prays every night, but considers himself an agnostic. He argues that even Billy Graham and the Pope are agnostics, too; “because nobody knows and nobody ever has known, including the Biblical prophets.”

Both of his grandfathers were Southern Baptist preachers, and he grew up in an ‘extremely strict’ environment. Baptized as a youngster, he felt nothing. Instead, the moment of truth came when he saw a Natalie Wood film, and experienced what he feels was the start of his spiritual quest. He lost interest in Christ as a result of another movie – Tarzan; “He captured me in a way that Jesus obviously had not.”

A red letter date was the first time he took LSD, which he describes as his most profound spiritual experience. “The one day of my life I would not exchange for any other.” He tells of the subsequent loss of ego brought about by the drug, but – ironically – comes off as one of the more egotistical interview subjects.

Film director David Lynch – a long standing practitioner of Transcendental Meditation – describes the intense bliss he experiences while meditating, and how if more people would practice the technique world peace would come about. He’s twice divorced, and a chain smoker. I wondered if Falsani ever questioned the logic of some of her interviewee’s claims. “I didn’t confront people with things. I asked them questions. Here he’s invited me into his home, I’ve never met the man before. I only knew him through his art, and it would be really arrogant of me to start judging him. I can tell you what he said, I can tell you how he appeared to me, and what it was like to be in his presence. And that’s what I tried to do with everybody in the book. Sometimes I had to sit on my hands and bite my tongue.” She laughs: “I won’t tell you with whom.”

Throughout, Falsani allows everyone their voice. Listening, and not confronting. “That was very intentional. Some people don’t understand that and have criticized the project since it started in the paper…what they see as a disconnect between words and actions. We very purposely approached people saying look, this is a non-judgmental venue. You get to talk about what you really believe with somebody who understands the lingo, who asks good questions and I’m not going to say if it’s real or right. I’m not going to confront you.’

’I wouldn’t pass judgment. That was the point. And figuring that if they get to say what they actually believe in a safe situation they’ll be more candid. And then people can read what they say, and they’re going to make their own judgments…I try very hard, I try to be very intentional about not judging the state of somebody’s soul. Because nobody knows that but you and God.”

She mentions Hugh Hefner as an example – an earlier interviewer was ready to judge Hefner – and had attempted to covert him. He was wary, expecting a similar agenda from Falsani. “And I didn’t come in with one. He was looking for it. He was waiting for me whip it out of my purse.”

Her non-confrontational approach has caused problems with some readers. “As frustrated as I get with Christians behaving badly, I’m an Evangelical. A lot of other Evangelicals would like to kick me out of the tent, and try to all the time. The meanest letters I get are from other Christians correcting me, ‘speaking the truth in love’ not so lovingly…”

Working as a religion writer – even for the Sun Times – carries with it a stigma. Provoking anger seems to go with the territory. “You write about religion you know you’re going to get smacked by somebody…”

She expresses empathy for writers working with Christian publications. Particularly publications with names as overt as Canadian Christianity: “I would imagine it makes it even more difficult for you, and that’s a sad commentary on how we’ve presented ourselves over the years, that people get this idea when you say Christian, or especially when you say Evangelical or born again, that it means your thought is judgmental and mean-spirited. That’s really unfortunate. And well-earned. I didn’t have that [problem], because they didn’t know what I was…You’ve got more of an uphill battle than I had.”

© John Cody 2006