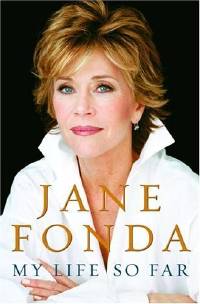

• Jane Fonda: My Life So Far, Random House, 2005

• Tony Hendra: Father Joe, Random House, 2004

• Anne Lamott: Plan B: Further Thoughts on Faith, Riverhead, 2005

THREE of the most inspirational, Christ-centred books released in the last year are readily available at bookstores across the country – but not likely in most Christian stores.

Jane Fonda, Tony Hendra and Anne Lamott have all recently chronicled their personal journeys to faith, offering rigid self-examinations of choices made, mistakes and triumphs. Each shares his or her story honestly and candidly, without cleaning up the messy bits. Through humour and pathos, each of them comes across as a genuine human being, humbled by their individual journeys.

Their roots could not be more dissimilar. Hendra’s parents were nominally Christian, but certainly not to the point of impacting him. Fonda and Lamott came from homes that were hostile to the gospel, their parents believing Christians to be ignorant and weak. Hendra’s family were British lower middleclass. Fonda came from privilege; her father Henry was Hollywood royalty. Lamott’s father was an alcoholic writer – two traits she inherited, although she’s been sober for years.

Throughout much of Father Joe, Hendra comes across as self-centred, on occasion quite unlikable and willing to hurt those closest to him for his own interest. It’s only later in life that he begins to understand and deal with this. Lamott – a struggling single mom – admits to being egotistical, self-absorbed and cripplingly insecure.

Even after a lifetime in the spotlight, Fonda’s exploits shock her as much as the reader. There’s no squeaky clean victory-to-victory God-has-blessed-me accounts here. Warts and all, the transformations are ongoing. The up side? As Fonda quotes from The Velveteen Rabbit, “once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

Each is strongly opinionated, though not always taking the same sides. Fonda and Lamott adamantly fight for women’s rights and rail against patriarchal church systems; and Lamott in particular is unwaveringly pro-choice.

Hendra – who at times borders on being a sexist pig – searches for churches still performing the Mass in Latin, unwilling to accept the changes brought about by Vatican II.

If they don’t square up with any party line – left or right, Democrat or Republican – it’s clear they’re saying what’s truly on their hearts. What they do agree on is Christ’s transforming power; and in a time when a North Carolina church is attempting to expel Democrats from the congregation, it’s vital to recognize that not all believers share the same political views.

All three deal head-on with their faith, regularly attend church and point to a personal relationship with their creator.

Nevertheless, odds are that the writers won’t be guests on Focus On the Family or The 700 Club anytime soon. There’s profanity, and frequent accountings of sordid exploits, along with the ensuing carnage – for which each author takes full accountability. Each book is a soul-searching expose, and brutally honest – just like real life should be. All three stories are well worth hearing.

These are believers, warts and all. Each knows their dark side, and without a doubt they are broken. That’s why they strike a common chord: it’s easy to relate to these people.

• Jane Fonda: My Life So Far, Random House, 2005

JANE FONDA divides her autobiography into three separate acts: ‘Gathering’ covers her first 30 years, who she would become, and “the scars that I would spend the next two acts recovering from, and also building upon”; ‘Seeking’ finds her looking outward, searching for meaning beyond herself; and finally, ‘Beginning’ explores her life since she turned 60. She chose the term “because — well, that’s what it feels like.” Throughout — living a storied life filled with controversy — she comes across as totally unpretentious.

JANE FONDA divides her autobiography into three separate acts: ‘Gathering’ covers her first 30 years, who she would become, and “the scars that I would spend the next two acts recovering from, and also building upon”; ‘Seeking’ finds her looking outward, searching for meaning beyond herself; and finally, ‘Beginning’ explores her life since she turned 60. She chose the term “because — well, that’s what it feels like.” Throughout — living a storied life filled with controversy — she comes across as totally unpretentious.

From the start, she faced obstacles. Her father, legendary actor Henry Fonda, appeared warm and caring on film, but was utterly cold to his own family (Brother Peter’s autobiography is entitled Don’t Tell Dad). Her mother’s suicide when Jane was 12 years old impacted her far deeper than she realized. By her teens she had set two key objectives — to win her father’s affection, and to never be ‘weak’ like her mother. Her father rarely noticed her, and she came to realize his disapproval was the best she could hope for. This led to a life of moral compromise, doing whatever it took to please men, regardless of her own feelings.

The lengths to which she would go attempting to please her partners is heartbreaking. Insecurity regarding her body led to a lengthy struggle with bulimia and anorexia, and breast implants in her late 40s. She became a sex kitten, strident political activist, fitness guru, and the wife of one of the world’s richest and most powerful men. All these roles, she came to realize, were attempts to please the men in her life.

Fear of appearing ‘bourgeois’ led to uncomfortable compromises in her first two marriages. Her first husband, French film director Roger Vadim, would frequently recruit other women to join the couple in bed. Concerned with appearing prudish, or losing her husband, she went along with anything he wanted, becoming “the Oscar winner of wildness, generosity, and forgiveness.” Some reviews have taken her to task for sensationalizing her sexual exploits; but they are essential to her story. Fonda decided to share these details in order to show how far she’s come, now realizing that this was marital betrayal couched in the ‘do your own thing’ ethos of the era.

Soon after winning her first Oscar (Klute 1971) she was pregnant, living with her second husband, political activist Tom Hayden. Hayden — who Fonda says felt threatened, and was dismissive of her success — constantly shamed her for her materialistic lifestyle. Once more attempting to avoid being labeled bourgeois, she sold all of her belongings — giving the money to various political causes — and shared a small rundown house with seven others. Her father disdainfully referred to it as ‘the shack.’ Fighting cockroaches and lacking laundry facilities, for over a decade — in between making movies — she would visit the local Laundromat twice a week. During this period she won her second Oscar (Coming Home 1978).

Her workout programs were initiated as a means to finance a camp she and Hayden had started; they soon took off, with Jane Fonda’s Workout becoming the biggest-selling video ever released, superceding her fame as an actress and activist.

When she married broadcasting czar Ted Turner in 1990, her lifestyle was once again turned upside down; she now had private jets and 23 luxury homes located around the world. But her attitude toward possessions remained largely unchanged — and since leaving Turner she has lived in her daughter’s modest guest bedroom, and is happier than she’s been in years.

According to Fonda, the men in her life were overachievers, willing to show sensitivity in a handful of areas, but absolutely lacking when it came to being emotionally available. All three husbands — like her father — had vowed to never show vulnerability. In each relationship, these larger-than-life figures with fragile egos would look to her for confirmation that they were really okay. If they were married to Jane Fonda, they must be. Conversely, she saw herself through their eyes: if she could marry a respected film director, a political maverick, and a corporate mogul, she must be okay.

Repeatedly, Fonda illustrates how smart, sophisticated women — because of unhealed childhood issues — can end up in such seemingly inexplicable situations. Privately humiliated by her husbands, to outsiders she appeared strong and independent; but underneath the public persona, she was anything but. For all her talk about human rights, she says, “I was the only person I could treat badly and consider that morally defensible.”

In each relationship, she would compartmentalize and ignore the pain. The power of denial — pretending everything was fine — only worked for so long. She would eventually accept that things weren’t working; but lack of self-esteem and fear of true intimacy meant solutions were half-hearted and destined to fail.

Like her father, she would leave her children for extended periods of time to make movies, or later to speak or protest various social issues, calling home once or twice a week, in the vain hope that long distance worrying would be interpreted as love. She paid a price for repeating the patterns she had experienced when she was growing up, although relationships with her kids appear to have since mended.

A lightning rod for controversy, she freely admits there was “hardly a mistake I didn’t make when it came to public utterances.” She was always sincere, but her work for Native rights, ending poverty, and most significantly, her efforts towards ending the war in Vietnam were met with hostility from much of the public. There’s a moving account of a late-’80s meeting with hostile Vietnam veterans. Still angry almost two decades later, they’re initially prepared to run Fonda out of town. After she’s given a chance to explain her position, they come to a place of mutual understanding and reconciliation.

She launched a lawsuit against the Nixon administration, and learned that between 1970 and 1973 the FBI, CIA, State Department, IRS, and White House all kept files on her. Post-Watergate, the government lost much of its power to infringe on an individual’s privacy, but after 9/11 the Bush administration implemented the Patriot Act. Fonda sees many similarities between Vietnam of the ’60s and ’70s, and today’s actions toward Iraq, and argues that in many ways the threat of terrorism is the new Communism — a catch-all adversary to justify questionable government actions.

Her father was an agnostic, who felt anyone who showed emotion or faith was ‘weak.’ He lumped therapy, religion, and pretty much anything that necessitates vulnerability as “crutches, all crutches.” Turner was hostile to Christians — he’d publicly called Christianity a religion for losers, and had taken it upon himself to rewrite the Ten Commandments as the ‘Ten Voluntary Initiatives.’

Living in Atlanta with Turner, she was exposed to churches on a regular basis for the first time. She had never known any Christians, and was shocked to meet intelligent, forward thinking believers, including President Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, and Ambassador Andrew Young. She realized she had carried a sense of emptiness since adolescence, and becoming a believer filled that void. She spoke with beliefnet.com last month about her decision to accept Christ: “It was very heavy, and — you know, it’s hard to get the words out these days because it’s so loaded politically, and it scares me to say it — but I was saved . . . Christianity is my spiritual home. This is where I’m meant to be.” Anne Lamott’s book Traveling Mercies was a major influence, confirming that one can retain their individuality while accepting Christ’s claims.

In the end, there’s little resentment evident in this book. She has forgiven and come to understand both of her parents, and made peace with her ex-husbands. At 67 years old, she’s currently involved in the feminist Christian movement, and works with young people focusing on issues of sexuality, early pregnancy, and parenting.

Her return to film after fifteen years, Monster In Law, was released last month. Characteristic of her pragmatic approach, Fonda took the role in order to finance her work with G-CAPP, the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention.

• Tony Hendra: Father Joe, Random House, 2004 (released in paperback May 31, 2005)

Tony Hendra was the managing editor of National Lampoon during the magazine’s heyday in the early ’70s. He played the band manager in the cult classic This is Spinal Tap, edited Spy Magazine, helped create and produce the British hit TV show Spitting Image. He’s published a number of satirical books, including Not the Bible and The Book of Bad Virtues. Going Too Far, his history of satire in the 1960s and ’70s, is an extensive work, the definitive study of the form. Simply put, the man knows comedy.

Tony Hendra was the managing editor of National Lampoon during the magazine’s heyday in the early ’70s. He played the band manager in the cult classic This is Spinal Tap, edited Spy Magazine, helped create and produce the British hit TV show Spitting Image. He’s published a number of satirical books, including Not the Bible and The Book of Bad Virtues. Going Too Far, his history of satire in the 1960s and ’70s, is an extensive work, the definitive study of the form. Simply put, the man knows comedy.

Father Joe chronicles his life-long friendship with an English Benedictine monk from Quarr Abbey on the Isle of Wight. His initial meeting is tense — at 14 years old he’s sent to meet with Father Joe after being discovered having an affair with the wife of his religious instructor. Expecting harsh punishment, Hendra is shocked to find Joe an attentive listener, understanding and accepting — quite unlike what he had come to expect from the church. This first encounter with Joe was “life changing.” For the first time he thought of someone else’s feelings — the woman’s — rather than his own, and felt compassion rather than passion. Father Joe was Christ to him — “unlike the pious, he didn’t speak of Christ very much. But then, neither did Christ.” Until then, “it was all on paper, abstract . . . it was true only in some parallel dimension, the dimension of religion. It had never been real. Not until . . . after my walk with Father Joe.” God was now real. He plunged in to religious instruction, becoming a self–described “Teenage Monk,” certain of his life’s path.

His steadfast determination is impressive. Letting nothing stand in his way, he is angered after being ‘tricked’ by a school teacher into winning a scholarship to Cambridge. Father Joe insists he must attend, but he vows to return to the Abbey as soon as possible.

That he ended up in sordid world of showbiz is a fascinating story in itself. The initial impetus is his exposure to the theatrical revue Beyond The Fringe. The 1960 production — a series of vignettes, parodies and monologues that included Peter Cook and Dudley Moore in the cast — was fresh and biting in its wit, taking on numerous sacred cows, including the Church of England and all manner of proper British institutions. For Hendra, it was almost a ‘Damascus road’ experience. He decided almost immediately that he could ‘save the world’ through comedy, and was soon performing on stage with John Cleese and Graham Chapman — both of whom would go on to create Monty Python’s Flying Circus. He left England, and ended up performing in the U.S. — including the Ed Sullivan Show in the late ’60s — moving on to National Lampoon a soon after.

He also made a royal mess of his life, with failed relationships, drug habits, divorce and a botched attempt at suicide. His own description of his fathering skills — “no father could be more selfish” — rings true. Anyone and everyone would be laid waste in his quest “to save the world through laughter.”

Slowly he began to comprehend that worldly success means nothing. Father Joe had quietly told him earlier, but Hendra refused to hear it; so Joe let him come to his own conclusions. He realized there was not any noble cause behind his satire, as he had long maintained. He was as morally suspect as his targets, entirely motivated by pride.

He credited Father Joe with helping him come to a crucial understanding. “With consummate skill he’d led me step-by-step to the realization that I had become a rather unpleasant person, that it was time to move on to a second phase — but without rejecting, as I was prone to do, everything I’d so far accomplished.” Not for the first time, he was amazed by Joe’s insight into the job.

Only after Joe’s death did he learn that hundreds of others had visited the monk on a regular basis. He didn’t share his successes, and never took credit. Another monk remarked that everyone thought they were Joe’s best friend. Hendra realized that “all of us were right. We were.” Joe counseled priests, clergy from various denominations, gays — everyone from a woman who had been born out of wedlock in the 1930s, to Princess Diana. Some continued the trek to the Abbey for as long as 60 years.

Hendra’s final description is telling: “Joe was a holy chameleon. To me he was irreverent and secular. To others he was an intensely spiritual guide; to others a mild but unyielding disciplinarian. To some he was a father, to some a mother. He always did what was appropriate and practical for the person he was with.” Like Jesus.

At times hilarious, this rich and deeply moving story is bolstered by excellent writing.

• Anne Lamott: Plan B: Further Thoughts on Faith, Riverhead, 2005

Plan B is Lamott’s sequel to 1999’s Traveling Mercies, which chronicled her bumpy road to faith. Her musings on life as a mature believer are every bit as entertaining and inspiring. She’s older, and while some of the issues have changed — no more tales of drunken debauchery and drug abuse — middle-aged weight gain and frustrations with raising her teenager bring new revelations. As with all of her books, the pearls of wisdom sit alongside profoundly human emotions.

Plan B is Lamott’s sequel to 1999’s Traveling Mercies, which chronicled her bumpy road to faith. Her musings on life as a mature believer are every bit as entertaining and inspiring. She’s older, and while some of the issues have changed — no more tales of drunken debauchery and drug abuse — middle-aged weight gain and frustrations with raising her teenager bring new revelations. As with all of her books, the pearls of wisdom sit alongside profoundly human emotions.

She writes about her son, a wide variety of friends, George W. Bush, her dog — she points out dogs are as close as some will ever get to understanding God’s love — and her church family.

Family is an ongoing theme. Lamott chronicled her son’s first year in Operating Instructions. He’s now a teenager, and they argue frequently about all kinds of issues, including her insistence that he attend church every second Sunday. His friends are believers, but he makes fun of Lamott for being a ‘Jesus freak.’ In spite of the sometimes tense relationship, he prays with her, and it’s clear they share a close bond.

In Traveling Mercies she wrote of her frustrations with her elderly mother. She’s since passed away, but Lamott is still angry — it took two years before she could even bring her mother’s ashes out of a hall closet. She comes to realize that “forgiveness means it finally becomes unimportant that you hit back. You’re done. It doesn’t necessarily mean that you want to have lunch with the person.” Thus, she finds a degree of peace, and can say goodbye.

She does consider one potential luncheon guest: George Bush. Bush appears frequently, and never favorably. She prays to feel love for him, likening him with a member of the family (of God) that you don’t necessarily feel affection for. She knows Jesus loves him and that He would have him over for lunch. She detests the fact that she’s called to love him, and prays to stop hating, realizing Jesus would eat with him — “even if he knew that the White House would probably call the police or Justice Department on him later for his radical positions.” Squaring Christ’s love with the current political climate is particularly tough. She writes: “Jesus was soft on crime. He’d never have been elected to anything.”

There are several poignant episodes; her son meeting his birth father for the first time, and the awkward road to connection. A friend in the later stages of terminal cancer, calling after too many well-meaning church-goers insist she should be happy because she was ‘going home to be with Jesus,’ and telling Lamott: “This is the type of thing that gives Christians a bad name. This, and the Inquisition.”

Delivering a college commencement speech, she offers advice that goes against what most institutes of higher learning would endorse, including not buying into what the world values. When she started receiving stature as a writer — a lifetime goal — it meant far less than she had expected. “When I finally made it, I felt like a greyhound catching the mechanical rabbit she’d been chasing for so long — discovering it was merely metal, wrapped up in cloth . . . it was fake. Fake doesn’t feed anything. Only spirit feeds spirit.”

Lamott is the real deal, warts and all, and feisty as ever.

© John Cody 2005