• Over the Rhine: Regent College, November 15

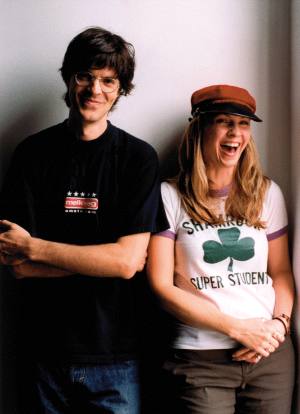

Over the last two decades, Over the Rhine has produced a body of work that far surpasses far more popular acts. Other players have come and gone, but in essence, Karin Bergquist and Lindford Detweiler are the heart of the band. Karin sings, Lindford plays guitar and piano, and they both write the material.

I spoke with Karin about their latest album, the music industry, and much more.

Bergquist and Detweiler first met while attending a small Quaker College in Canton, Ohio. They formed Over the Rhine in 1990, and quickly developed a reputation for producing rich, haunting songs that reveal a distinct spiritual dynamic. To date, they’ve released nine albums.

Six years after starting the band, Bergquist and Detweiler got married. Both took it for granted that they were going to be together for the duration.

In 2003, shortly after releasing Ohio they realized their marriage was in serious trouble. They took drastic steps. “We canceled the tour. A pretty significant tour. We’d just made this big old double album, and we were quite pleased with ourselves. It was going well and we loved that record and had a lot of fun making it.

“[But] we’d run out of steam. We hit a point where we were separated and still working on this tour, and it became too much. We pulled the plug and went home. Which was kind of scary, you don’t ever want to do that on your career.

“To our label’s credit and our booking agent’s credit, they both said ‘we totally understand, you go home and do what you have to do.’ And that’s rare. So we went home and we pulled it together. We didn’t know what was to happen, but we had to deal with it.

“We had been artists with a capital ‘A.’ We put everything into the band, into the music, and because you are a musician or a writer or artist you live by different rules. You think you do. You think you do, and you don’t, that’s the thing. And it takes a little bit of maturity to learn that. And we realized, no if you’re a married couple, you have to play by the same rules as everybody else does, and you have to nurture that relationship, or it will wither on the vine. And we didn’t know that. Neither of us had the tools to do that. Fortunately we had the resources to pull it together and to make a better marriage than we had, and realized that we had to prioritize. Without the marriage there would be nothing else, anyway. We probably wouldn’t enjoy working together like we do, and there would be no Over The Rhine. We could go on with solo careers, but it just seemed wrong. We both knew that, so we put all of our efforts and energies into repairing our marriage and thank heavens we did.”

“We had been artists with a capital ‘A.’ We put everything into the band, into the music, and because you are a musician or a writer or artist you live by different rules. You think you do. You think you do, and you don’t, that’s the thing. And it takes a little bit of maturity to learn that. And we realized, no if you’re a married couple, you have to play by the same rules as everybody else does, and you have to nurture that relationship, or it will wither on the vine. And we didn’t know that. Neither of us had the tools to do that. Fortunately we had the resources to pull it together and to make a better marriage than we had, and realized that we had to prioritize. Without the marriage there would be nothing else, anyway. We probably wouldn’t enjoy working together like we do, and there would be no Over The Rhine. We could go on with solo careers, but it just seemed wrong. We both knew that, so we put all of our efforts and energies into repairing our marriage and thank heavens we did.”

They knew they couldn’t do it on their own.

“We have a community of friends here that we leaned heavily on. People that we’d known for years, people here in this area – Cincinnati area – that were why we didn’t move to L.A. or New York or Nashville, because we really needed these people, and they helped us through this time.

They also saw a counselor. “We had a fantastic marriage counselor. And good counseling…it can make or break. Fortunately, this person that we’d worked with we had known from before…Lindford and I are both very much into doing personal homework. We’re always navel-gazing [laughs]. And we’re both into using tools to make that more accessible, and he helped us a whole lot.”

Navel gazing is one thing. Dealing with marital problems can be far tougher. “Absolutely. And the relationship that we have, we’re together 24/7. We work together, we tour together, we come home together. You can’t have a lot of self-loathing in a relationship like that, because it gets pretty ugly. You’ve got to work on your stuff. You can’t just slack off.”

Being an artist – especial an artist with a capitol ‘A’ – offers all sorts of excuses to hide from one’s issues. “Oh yeah. Oh, it’s a great excuse. A great excuse. I think a lot of people use it for an excuse for drinking. For anything… But if you’re not a musician, or a writer, or an artist, you’re going to find an excuse somewhere else. But it always finds you; it’s going to find you, whatever that weakness is. Whatever that thing is that you’ve got to work on, it’ll find you, and you choose to run from it for 40 years, or you face it and deal with it.”

I wondered what sort of role their faith played during this time.

“It played a part… We were both raised in the church. Linford was raised far more conservatively. He was raised Mennonite. My upbringing was erratic – it was a Methodist, Pentecostal, nondenominational…” She starts to laugh. “It was everything. It was confusing…

“I’ve seen marriages that have stayed together because of their religious convictions.” But with no love evident between the partners? “We’ve seen that firsthand, and we don’t agree with that. That’s more of an abuse of your faith than a healthy way to live it. So we weren’t going to do that. We knew that. We both feel like it’s worse to give a false representation. If you’re faking a healthy marriage people are going to know. So what are you doing for the kingdom if you’re just faking it? That’s kind of how we felt. What [faith] did do for us, I think it gave us some footing. Our counselor had the same footing. But what he said to us wasn’t ‘you have to stay together because of your faith. And because of the Church and because of…’ What he said to each of us was ‘I am not going to let you stay in a bad marriage.’ And that was refreshing, because he’d been through a bad one himself. And I knew at that point I could breathe, and I knew I could trust him, because that’s not what I wanted. I’d seen that. My husband and I both lived with that in other situations and we did not want that. And so we were going to be all right. That was a big part of it.”

For a while, therapy consisted of opening a bottle of wine each night and talking until it was empty. She laughs. “Yeah. We were at the point where we really weren’t talking very well. We’d spent our first Christmas in I don’t know how many years apart. Lindford went to Scotland to be with our former guitar player and friend, and I went to California to be with my sister. I flew home on Christmas Eve and he was going to pick me up. He had phoned me a few times from Scotland, and he was a bit tipsy, and that’s not my husband at all. So our good Scottish friend did what he should have done and took him out and lightened him up a bit. And he called me a couple of times, and I thought ‘oh, this is interesting.’ He was talking, and we were talking, and that was good. That was a breakthrough in some ways. I think just being away from each other helped. Missing it.

“And then he picked me up on Christmas Eve – he was late, and he came running into the airport and his voice cracked, and it was a very endearing moment, because it’s not what he wanted. I think at that point he had decided he really wanted to save this marriage. And I didn’t know what to think. So he picks me up, his voice cracks, he’s late, it was very endearing, very sweet. We got home and he had taken a honeysuckle branch from the backyard, which in the winter is just a very ugly looking thing. Just the naked branch with twigs on it. And he [had] cut it off and put it in a pot with bricks and wrapped white lights all around it, and that was our Christmas tree that year. I have a birthday near Christmas and it’s always been a big deal to get a tree and do it together. We’d always gone out and gotten these big beautiful trees. Well this year we didn’t, but he still wanted to make something really beautiful out of this very nasty thing. And he’d gone out and bought a case of wine, and he said ‘Meet me in the kitchen,’ which is where all the talking takes place. He pulled out the bottle and said ‘let’s start talking’ and it was good. I think in marriages and relationships it’s fairly typical for one person to feel like they’re doing more of the work some of the time. And it goes back and forth if it’s a healthy relationship. And I think it was kind of his time at that point to say ‘Okay. Here’s what we’re gonna do,’ and take control of it and say ‘this is how we’re going to get through this.’ I found great comfort in that leadership that he showed. And it was hard. It was really, really hard. But that’s what we did, and we made it. I’m really grateful. It’s been three or four years since that all went down, and boy I’m just really grateful.”

Battered but wiser, in hindsight Bergquist feels their problems could have been dealt with far earlier had they been less complacent. “We wish that we had gotten premarital counseling. We didn’t, and we didn’t think we needed it. We thought we knew everything. And we found out some years later that we did [need it]. Oh yeah, we did.”

In a recent interview Lindford made it clear he was just as arrogant in the beginning: “We never would have dreamt of doing pre-marital counseling – that was for losers who live in the suburbs. We’re artists!”

When I mention the idea of churches refusing to marry couples unless they participate in mandatory counseling, she’s all for it. “I think that would be a really good idea, and I think that would set a precedent for the next generation. You might see some statistics change if we did that.”

Not surprisingly, music became part of the therapy. “Inevitably we did end up working through it musically. It wasn’t deliberate or intentional; it’s just out of habit.

It’s the way we work through things. We just go to the piano and sit down and things come out.

“There was one song on the record called ‘Little Did I Know,’ and Linford began writing the song during this time, before we turned a real corner. I heard the chord changes as I’d walk through the house, and I knew. I didn’t hear the melody or the words, I just heard the chord changes, and I thought. ‘Oh no, don’t you dare.’ I knew what the song was about; I knew where it was going intuitively, because I’d known him for so long. And I was kind of ticked. Weeks later, I finally got to the point where I said ‘okay, let me hear this song.’ And I knew what it was gonna be about.” Fortunately, she loved it; “It’s really a gorgeous song.”

Marital strife has been the inspiration behind a number of classic albums. Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot Out The Lights, Marvin Gaye’s Here, My Dear, Rosanne Cash’s Interiors, and Bob Dylan’s Blood On the Tracks are all high water marks in their creator’s respective careers. Drunkards Prayer is cut from the same cloth. Unlike every other album listed, however, this marriage survived.

The disc was recorded in the couple’s living room with scaled down instrumentation. Dealing with their relationship in unflinching, honest terms, it’s adult music for adult minds. Odds are good these songs won’t be heard on American Idol anytime soon.

Initially, singing the songs in concert was hard.

“At first it was really painful. I’m a very emotional performer. I’m singing these songs and I’m not just singing them. I’m actually living them. Because they’re so close to me, they’re so close to what we’ve been through. As time passes, they do become a lot easier to sing and it’s more for the show. For the performance, for the evening, for the audience.”

Literary works have always been an influence on the couple. The title of their debut album ‘Til We Have Faces (1991) took it’s name from a C.S. Lewis novel, and they’ve name-checked everyone from T.S. Eliot to Anne Lamott (‘she’s a biggie”) as inspiring their own work.

Karin brings up Maya Angelo as a long-time favorite. “She sort of mothered me through my thirties. And my twenties. I give her a lot of credit for raising me, really.”

For the past few years they’ve been part the Glenn Workshop, an annual event sponsored by Image, a literary and arts quarterly informed by religious faith. “We’ve had this wonderful relationship with Image magazine; we absolutely love it. We’ve been hobnobbing with these brilliant writers and poets. We go there for a week and we get plastered, just drunk on all this great stuff. I come home reading B.H. Fairchild. His poetry is absolutely incredible. Just brilliant, beautiful. And Scott Cairns; another poet that I just love. She mentions Wendell Berry, Erin McGraw, Andrew Hudgins, Luci Shaw, and Thomas Lynch as writers she admires, each of whom flies in the face of the media’s all too common portrayal of the Christian arts community as blindly following a right-wing political agenda.

She’d like to see believers like these gain greater visibility. Especially those who go against the grain; “…like-thinking Christians, or thinking people of faith that aren’t afraid to really address things and say things …because it’s the only way for us to really get word out that we’re thinking, and that we’re aware. And we know how to vote. You know, some of us.” She begins to laugh. “I can’t believe I said that. I don’t care. Alright, I’m done with that.”

They’re good friends with Barry Mosher, a venerated artist and writer. She’s particularly enamored with his work on the Pennyroyal Caxton Bible. “It’s quite a stunning version of the Bible. Just incredible. His illustrations are the antithesis of further romanticized saccharin blue-eyed Jesus. He’s gone the other way. It’s very real. I think it’s inspired – it’s beautiful. He’s a retired minister. I don’t want to speak for him – but he certainly questions his faith now more than anything. He’s a dear man; a brilliant talent with a lot of questions, who’s been through a really interesting life.”

Bergquist has begun writing children’s stories, which Mosher has offered to illustrate. “We’ve been collaborating a little bit, or talking about it. So I would like to put out a children’s book or two before it’s all said and done. It might be fun to do a CD with that at some point.”

I mention Peter Himmelman, who in addition to maintaining a prolific recording career and composing music for the television show Bones, has released a series of children’s albums. Of all of these projects, he claims that writing the children’s songs is the discipline he takes most seriously.

“I think that’s brilliant – that’s really respectable. People get really selfish with their gifts, and abuse it. I think the industry is the way it is – here I go – kind of the way it is because people aren’t thinking like Peter Himmelman, and aren’t being more considerate of the next generation and what’s coming up. But that’s what I think.” She laughs. “I’ll get off my soapbox.”

Probably not a good time to ask her opinion of American Idol. Aw, what the heck. “Oh boy. I think it’s entertainment, but in it’s lowest common denominator. It reduces music to its lowest and most inefficient form. That form of competition is a real ugly way to enjoy music. Music started out in many capacities, one of which was a noble way of communicating stories, and deaths and births and wars and rumors of wars from village to village by a troubadour. It started off as being a very useful sort of tool, among other things. I think we’ve gotten to the point where we want money so badly, and if something doesn’t have a price tag attached we don’t know how to appreciate it. And so a lot of really great music gets overlooked. I don’t think music is a competition. But I’m just an old jaded woman,” she laughs.

Over the last decade, the music business has undergone radical shifts. The old business models are obsolete.

“I know acts that have had millions of dollars poured into their music, and they’ve had a hit or two but can’t fill a club. And it’s because they don’t have the legwork and the street history that other musicians have. I tend to have a lot of respect for people that have survived this industry by doing it one town at the time. It’s a hard way to do it; it’s not an easy way to make a living. But it’s respectable. I don’t think there’s anything that can replace that.” She brings up Shawn Colvin as an example; “We opened for Shawn as a solo act, and she’s amazing. I asked her – because she’s so confident, and it was a real rowdy crowd – but she had them in the palm of her hand. She said it just came from years and years of night after night, and hard work. And I respect that.”

They recently left Back Porch, the label that released their last two discs. “We’re independent at this point. [Back Porch] was sort of subsumed into a bigger label, which happens all the time. Fortunately the timing was perfect. This is the second time in our career where we’ve done a few records with a label, and then, ‘contracts up,’ and about that time they get sucked into the void. So we’re good, we’re in the clear. It wasn’t ugly.”

They retain ownership of the Back Porch albums. “We got smart and we had a great lawyer. He negotiated this for us. After a period of years the rights revert back to us.”

Rights to their earlier releases remain elusive. “That’s kind of a no man’s land. From this point on, we have to be really careful about what we sign and who we sign with.

“We’re independent, and we’re okay with that. We’re debating whether to just fire up our own label, our own imprint and just do more licensing.”

They recently released Live From Nowhere: Volume One through their website. An excellent collection of recent concert performances, it includes four songs from Drunkard’s Prayer, material from earlier albums and covers of a few old standards. It’s the first in a planned series of annual releases.

“At this point we have a couple of deals we’re considering and would love to have a good working relationship, but it’s such a dangerous thing to do. After 15 years of making your own music, it becomes your retirement. More and more I sound like an old fuddy-duddy, but I don’t want to give my music away to somebody and get 20 years down the road and not have anything. That’s all I’ve got, because there is no retirement plan for musicians. [There’s] nothing like that for us.”

Their Vancouver appearance will be at Regent College, a decidedly Christian institution. While their records appear on mainstream labels, they’re happy to play the venue. “When we started the band several years ago, the one thing we decided was we weren’t going to be exclusive in the venues that we performed in. We wanted to perform to whoever would walk up on the street. So by that, we weren’t going to play exclusively bars and we weren’t going to play exclusively churches. We don’t want to play in places where an audience feels built-in. We want to have the freedom to play to anyone. If someone asks us to come and play we’ll look it over. And we’ll come and play. We usually do recommend that they know really what were about. We’ve had a couple – it’s only happened twice in all these years – but we have had a couple of fairly conservative colleges invite us and then someone on the board would notice a lyric or a photograph. And then ban us. I find it absolutely hilarious, but it kind of gives us some kind of a strange street cred in a way. But it’s only happened twice. Our main thing is we just want to play for whoever gets it. And we’ll come.”

© John Cody 2006