Half a decade after his passing, the steady stream of Johnny Cash-related product shows little sign of slowing down. Fortunately, the majority of releases are well worth seeking out.

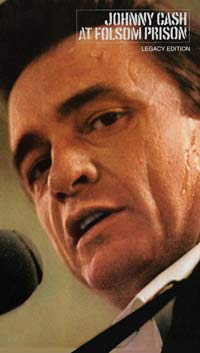

Hot on the heels of the stellar Johnny Cash at San Quentin box set comes Sony/Legacy’s expanded treatment of his career-defining Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison.

The original albums were recorded less than a year apart, but the circumstances were decidedly different; by the time San Quentin was released in 1969, his personal and professional lives were ascending to previously unimagined heights.

The original albums were recorded less than a year apart, but the circumstances were decidedly different; by the time San Quentin was released in 1969, his personal and professional lives were ascending to previously unimagined heights.

That was hardly the case in January, 1968, when he appeared at Folsom Prison. The Man In Black’s career was at its lowest ebb; it had been five years since the last hit, and his most recent release, Carryin’ On with Johnny Cash & June Carter had peaked at a dismal #194.

Cash had been playing prisons for over a decade – pretty much his entire career up to that point. This was his fourth visit to Folsom, but the first to be recorded.

There’s a sense of danger, both from the audience – this was a maximum security facility, after all – and Johnny himself, who was freshly clean from a longtime amphetamine addiction. The physical cost was readily apparent; along with the trademark black suit, his gaunt, almost skeletal appearance brings to mind an undertaker as much as an entertainer.  Footage from a 1965 TV show – scratching, twitching and clearly out of his head – offers stark evidence of just how far the habit had progressed. Despite long periods of sobriety, the battle with addiction would rage on and off for the rest of his life.

Footage from a 1965 TV show – scratching, twitching and clearly out of his head – offers stark evidence of just how far the habit had progressed. Despite long periods of sobriety, the battle with addiction would rage on and off for the rest of his life.

Merle Haggard – who had been an inmate at a Cash appearance in San Quentin a few years before – notes that had Cash not been a celebrity, he likely would have ended up serving time himself; many inside the walls had done far less, but lacked the built-in protection fame provides.

Cash was well aware of his good fortune. His jail record consisted of a few hours locked up for drunken behavior. Nevertheless, he related to the inmates on a level far more profound than as a mere entertainer.

Much of the material focused on topics the prisoners knew all too well. ‘The Long Black Veil,’ ‘Cocaine Blues’ and ‘Joe Bean’ are all songs of incarceration. ‘Folsom Prison Blues,’ recorded during his Sun Records days, had been in the repertoire for years – but was particularly fitting in this setting.

Alongside a now complete first set, the previously unreleased second set – recorded as backup in case the earlier recordings were unusable – is included, adding another 31 tracks to the original LP’s 16 songs. Johnny, June, Mother Maybelline and the Carter Sisters, Carl Perkins and the Statler Brothers are all allotted extra material.

Alongside a now complete first set, the previously unreleased second set – recorded as backup in case the earlier recordings were unusable – is included, adding another 31 tracks to the original LP’s 16 songs. Johnny, June, Mother Maybelline and the Carter Sisters, Carl Perkins and the Statler Brothers are all allotted extra material.

If the original album sounded ragged and on the verge of losing control in edited form, now – without the time constraints – things are even wilder. Out of tune guitars, missed notes, and no-longer-deleted expletives make for an eye and ear-opening experience.

In addition to a two hour documentary the DVD includes numerous extras – including expanded interviews with band members and prisoners.

The account of inmate Glen Sherley is especially poignant. Prior to the concert, the prison chaplain had given Cash a tape of Sherley’s ‘Greystone Chapel,’ a gospel number about clinging to one’s faith inside the prison’s walls. Johnny learned the song, and much to Sherley’s shock and delight, included it in his performance.

Cash became actively involved in Sherley’s rehabilitation. Enlisting Billy Graham’s support, he successfully lobbied for parole, securing Sherley a record deal and bringing him on tour after his release.  Despite everyone’s best intentions, things did not go well. Adapting to life outside prison proved harder than anticipated, and Sherley began drinking heavily. After threatening members of Cash’s troupe, he was let go. Eventually, he took his own life.

Despite everyone’s best intentions, things did not go well. Adapting to life outside prison proved harder than anticipated, and Sherley began drinking heavily. After threatening members of Cash’s troupe, he was let go. Eventually, he took his own life.

Rosanne Cash reflects on the tragedy, observing that her father; “had an inflated sense of his own power about his ability to change some of these men’s lives…and it didn’t turn out well all the time…He was a real man with grave faults and great genius and beauty in him, but he wasn’t this guy who could save you or anyone else.”

Cash returned to Folsom for one more performance in 1977 – which was not recorded – but the pressure wore him down. Eventually, he stopped playing prisons altogether.

Cash returned to Folsom for one more performance in 1977 – which was not recorded – but the pressure wore him down. Eventually, he stopped playing prisons altogether.

In hindsight, Rosanne believes the 1968 appearance signified her father’s own personal liberation; “…that was the moment that he came into the light … when he embodied who he really was.”

Much was to occur in the wake of the recording. Cash and June Carter were married two months later, and the LP went on to log over two years on the pop charts, reaching double platinum sales – by far his biggest success to that point.

Before it had even finished its run, San Quentin was released – peaking and #1, where it remained for an entire month during the summer of ‘69. By then The Johnny Cash Show had debuted on ABC TV, cementing his stature as an American icon.

© John Cody 2009