Judee Sill was many things; a prostitute, armed robber, junkie, jail bird – and arguably the most talented of all the seventies singer-songwriters.

During her lifetime she released two albums – each of which received critical acclaim, yet barely registered with the public. Three decades on, her music is at last finding it’s audience with a whole new generation.

Hers is a story of self-destruction, missed opportunities, but – most importantly – artistic triumph.

Hers is a story of self-destruction, missed opportunities, but – most importantly – artistic triumph.

Sill described her music as ‘country-cult-baroque.’ Playing piano and guitar with string and brass accompaniment, her songs dealt with Christian spirituality, metaphysics, rapture and redemption, and were laden with classical music overtones.

She once told a reporter her only influences were Bach, Ray Charles and Pythagoras – the Greek philosopher who taught of a mystic relationship between mathematics and music).

Sill spent her entire life – 35 years – in California. Born in 1944 to alcoholic parents, her father was a self-styled Indiana Jones type who had worked variously as a cameraman at Paramount Studios and an animal importer before buying a bar in Oakland when Judee was three years old. She would hang out for hours, playing the bar’s piano. When her dad died five years later, Sill’s mother returned to Los Angeles and married another alcoholic.

Drinking and violence were common in the home, and Sill alleged she was sexually abused by her step-father. She began experimenting with drugs, and participated in a half dozen armed robberies while in high school – which resulted in a nine-month stint in the state reform school. During her stay she played organ in the chapel – discovering the hymns that would inform so much of her songwriting.

Reform school did little to straighten her out. Upon release, she married on a whim; her parents had the marriage annulled. Her husband would later die in a river rafting accident while high on LSD.

In 1963 Sill enrolled in San Fernando Valley Junior College, majoring in art and playing piano in the school orchestra. She moved in with a drug dealer who played bass and took up the instrument herself. She was only 19, but lied about her age and began taking gigs in local bars.

Meanwhile, the petty crimes continued. During this period her mother and only brother died, and she began to develop a fascination with religious philosophy, exploring Christianity, Rosicrucism, Theosophy, New Thought and the occult.

She met Bob Harris, a piano player who introduced her to heroin. They were soon married, and began playing together as a duo in L.A.’s seedier bars. Heroin was the main concern, and before long they were reduced to living out of a car, with Sill working as a prostitute, turning tricks in order to support her $150 a day habit. She later told Rolling Stone: “All I really cared about was getting that needle in my vein.”

She got clean a few years later, while doing time in the L.A. Country jail for a narcotic conviction and writing bad checks. She had a vision of herself as a songwriter: “I got out of the drug thing and started using all this fierce gusto within me.”

She began writing songs in jail. Her very first attempt; ‘Dead Time Bummer Blues,’ was covered by L.A. garage rockers The Leaves (‘Hey Joe’).

Her spiritual quest informed much of her writing. Heavenly and temporal love were constant themes. She had been through many relationships, and lust, rapture, and redemption intermingled.

In 1969 Jim Pons – who had played bass for the Leaves – joined the Turtles, a far more successful act with a long string of hit records, and offered her a paid position writing songs for Blimp; the band’s production company.

I spoke with Mark Volman, who as vocalist for the Turtles was able to fill in a few details; “We started a company called Blimp…We wanted to aid and abet other artists, to creatively have some place to do it… Everybody had a say in what we were signing; it wasn’t something we could just casually accept. Jim played some of Judee’s material, and we all agreed that that was something we wanted to put our money into. So we signed Judee, and [she] received a monthly stipend to write songs for Blimp – or for herself, however you saw it.”

In an attempt to jump start Sill’s career, the Turtles recorded her song ‘Lady-O.’ Judee arranged the strings and played guitar on the track.

The next step was to secure a record deal as an artist. It proved to be far more problematic. “We went to White Whale [the Turtles were signed to the label], and they turned her down.” The band was fighting with White Whale at the time, and were about to break up. ‘Lady-O would be their last official single.

“And then Jim Pons and John (Beck – guitarist for the Leaves) tried to make a deal with other labels – I don’t think that they were successful, not because no one wanted to work with her, but because Jim and John were not really the kind of people that record companies wanted to work with. They weren’t – unfortunately – managers per se. And that was a problem.

“By that time we had pretty much given up on Judee. The record company deal had fallen apart, so we didn’t have the power to really do anything with her. At that point she went and signed a deal with Geffen…The album that would eventually come on Asylum contained the music that she wrote for us.”

David Geffen was then becoming a major player in the entertainment industry. He managed Crosby, Stills and Nash, and was about to start his own label, Asylum Records. The prestigious roster would include Bob Dylan, Jackson Browne, Joni Mitchell and the Eagles. He picked Sill for the label’s debut release.

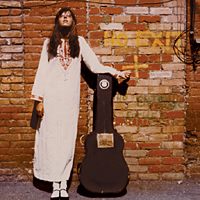

The self-titled debut album came out in 1971.

The self-titled debut album came out in 1971.

Pons and Beck stayed on as co-producers along with Henry Lewy, who had worked with the Flying Burrito Brothers and Joni Mitchell.

Harris – by now Sill’s ex-husband – orchestrated strings and brass. Coupled with her vibrato-less vocals – at times multi-tracked – the disc bore an absolutely unique sound. Excepting the pedal steel guitar, it was all acoustic instruments.

Visions of the eternal run throughout.

‘Crayon Angels’ deals with false prophets; “Crayon Angel songs are slightly out of tune/But I’m sure I’m not to blame/Nothin’s happened but I think it will soon/So I sit here waitin’ for God and a train/To the Astral plane.”

‘Enchanted Sky Machines’ was about end times, and made clear where she stood theologically; “Then when the skeptics are wonderin’/where all the faithful have flown/we’ll be on enchanted sky machines/the gentle are going home.”

Sill rarely minced words. As she explained regarding ‘Ridge Runner;’ “I had another divine inspiration on how noble it is to not fake it. How doubt can be an ally, really in the long run, as far as your spiritual evolution goes…”

Her most popular song, ‘Jesus Was A Cross Maker’ was a last minute addition produced by Graham Nash. It’s the only song she recorded that actually mentions Jesus by name.’ Ironically, it’s not about theological concerns. It was inspired by a failed relationship with singer-songwriter J.D. Souther. Her explanation was typically forthright; “I knew that even that bastard wasn’t beyond redemption.” Both the Hollies and Mama Cass Elliot covered the song. Years later Souther would remember Sill with great admiration; “there was nobody more important on the L.A. singer-songwriter scene.”

The album garnered exceptional reviews; Rolling Stone raved, and Newsweek labeled her songs ‘spaced-out spirituals’ and declared her ‘one of the most promising new singers in the business.’

For all the positive press, sales were dismal. The album never even placed in the Billboard top 200 charts.

Most of her songs were explicitly religious, but had little in common with the more dogmatic or evangelic material that the Jesus Music scene was producing at the same time. Her interest in Christianity was far more than intellectual curiosity – she was baptized by Pat Boone in his swimming pool, and once described Christ as an elusive lover – “My vision of my animus.”

Sill took over the arranging chores for the follow-up, 1973’s Heart Food.

Sill took over the arranging chores for the follow-up, 1973’s Heart Food.

Christ continues to be a constant presence, referred to as a ‘Soldier of the Heart,’ and a ‘Vigilante.’

‘The Donor’ – at eight minutes the longest track she ever recorded – incorporates the ‘Kyrie Eleison.’ Text from the traditional Catholic mass. It’s an epic achievement, and comes across like Brian Wilson at his most creative during the Smile era.

‘The Pearl’ is a cautionary take on drug abuse; “I been lookin’ for someone/who sells truth by the pound/then I saw the dealer and his friend arrive/but their gifts looked grim/…I found a way outside myself to make my spirit climb/And I coulda shinnied on up/but my rope was made of wind” Sadly, her own drug use was increasing.

‘The Pearl’ is a cautionary take on drug abuse; “I been lookin’ for someone/who sells truth by the pound/then I saw the dealer and his friend arrive/but their gifts looked grim/…I found a way outside myself to make my spirit climb/And I coulda shinnied on up/but my rope was made of wind” Sadly, her own drug use was increasing.

XTC leader Andy Partridge counts Sill as a major influence on his band, and claims her music contains “some of the most achingly beautiful melodies and chord structures I have ever heard.” He describes ‘The Kiss’ is “the most beautiful song ever recorded.”

As with her debut, the album was received with glowing reviews. The Village Voice called her as a ‘mad saint.’ But there were problems. She had gained a reputation for being difficult: refusing to perform live unless presented in her best light. Unwilling to open for other acts, and not popular enough to warrant headliner status, live appearances were rare.

Worse, she had alienated Geffen by outing him – referring to his homosexuality in an interview, years before he went public. Geffen was furious, and immediately pulled advertising for the disc. Without support, the album disappeared. Sales didn’t even equal those of her debut.

After the falling out, it was impossible to generate interest, or sign with another label. Some speculate that Geffen was powerful enough to ensure she would never record again. For all intent and purpose, her recording career was over.

Sill was involved in a series of accidents – breaking her tailbone in a fall, and ruptured her back in a car accident. A series of botched surgeries worsened the condition, leaving her in constant pain and confined to bed for close to a year.

Her drug use accelerated. In addition to painkillers, she returned to heroin and developed a cocaine habit.

Meanwhile, she continued to write, and recorded a follow-up to Heartfood in 1974.

Instead of reflecting her diminished state, the songs were full of joy, based around hopes of heavenly promise: “…the last one comes home/To praise His name/Burn each old house down/With your merciful flame/Won’t you burn out/All the sin and pain/’Til every corner stone/Sings the glad refrain…”(‘The Good Ship Omega, Alpha Bound’).

Many focus on end times, including ‘The Living End;’ “Fire of Heaven/It’s sink or swim/By lightning driven/By grace within/I just wonder when/There’s going to be rolling, tumbling/New day coming” and ‘The Apocalypse Express;’ ‘Take heart, take heart/Don’t back down/When the big train comes/Hang on, hang on”

The basic sessions with a four-piece band were recorded in a day. Her vocals were live, and then augmented with up to seven part overdubbed harmonies. Without record company support, there was no budget for strings or horns.

Sill designed the art work herself, going so far as to include the Asylum logo, in hopes that Geffen would come back. When that didn’t happen, the record was abandoned, remaining unreleased until 2005.

Continuing her downward slide, Sill disappeared from the scene. She died from an overdose – cause of death was listed as ‘acute cocaine and codeine intoxication’ – in 1979, the day after Thanksgiving. By then she was long forgotten, and her passing didn’t even make the obits. Many friends and fans didn’t learn of her death until years afterwards.

In 2003 Rhino Records Handmade imprint released limited editions of both of her albums, making them available for the first time in thirty years. Each was doubled in length with outtakes and live tracks. The live material showed she was a mesmerizing performer in concert.

Only 2500 copies were printed of each album, and they quickly sold out.

Her music has aged well. If anything, it’s even more refreshing today, when so many acts are overly-mannered and affected, to hear such purity coupled with a bold vision.

Two years later, both albums were reissued on both Cd and vinyl, but without any of the bonus tracks, and then again as limited editions with gatefold sleeves.

For those who missed the Rhino Handmade editions, last year Abracadabra compiled everything from those releases into one double disc set.

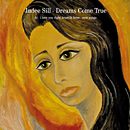

A double disc set of Dreams Come True – which she subtitled Hi I Love You Right Heartily Here – New Songs includes everything from what was to be Sill’s third album along with bonus tracks and a 68-page booklet.

A double disc set of Dreams Come True – which she subtitled Hi I Love You Right Heartily Here – New Songs includes everything from what was to be Sill’s third album along with bonus tracks and a 68-page booklet.

This month see yet another title added to her discography; Live in London: The BBC Recordings 1972-1973 consists of two previously unreleased performances, with Sill alone on guitar and piano.

Thirty years on, Volman is hardly surprised by the belated recognition Sill is finally receiving; “No – I was surprised it didn’t happen then.” He’s blunt in his estimation as to why so little success initially; “People are stupid. That’s all you can ever say about something like that. She was a very talented, incredibly talented songwriter. You listen to it today; it’s very much the cornerstone of what many of these young girl singers are doing. And I think she’s still a better songwriter than 90% of them.”

When it came to getting straight, in many ways the rock scene was as dangerous an environment as jail; “The music business has a way of making you feel like you’re exempt to what the real world goes through. There’s kind of a false security in terms of the fact that it’s impossible to consider that you could die.” Volman witnessed the destructive habits up close, when Sill was “pounding drugs – pretty much ruled by it, not so much by choice. And that was a big difference (from her peers) – I was always surprised at that. But Judee came into the music business already in that way. When she came along, she was already carving a niche in life that was already fairly deadly. Which was unfortunate, because you couldn’t really save her.”

He saw little evidence of the devout nature so many of her songs revealed. “I think Judy probably had a spiritual side to her, but her addictive personality really kind of swept her up before she could really do anything except write about it…”

One has to concur – it’s more of a surprise that these records didn’t succeeded the first time than it is that they’re finally finding an audience.

The more shocking elements of Sill’s story invariably get attention, but in the end it’s the music that remains.

© John Cody 2007