• The Gospel According to the Beatles, by Steve Turner, Westminster John Knox Press

Steve Turner’s latest book, The Gospel According To The Beatles, was hailed as “One of the most important works on the Beatles published in recent years” by the British Beatles Fan Club Magazine.

Steve Turner’s latest book, The Gospel According To The Beatles, was hailed as “One of the most important works on the Beatles published in recent years” by the British Beatles Fan Club Magazine.

He certainly knows his subject well; Turner’s career began when he was published in a 1969 issue of Beatles Monthly, and he’s already written one book on the band: A Hard Day’s Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatle’s Song, which has sold in excess of 250,000 copies.

His achievements are impressive, in addition to writing well-received biographies on Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, Marvin Gaye, Beat Generation icon Jack Kerouac and Johnny Cash, he’s also an accomplished poet, with his collections of children’s poems among the best selling volumes of contemporary poetry in Britain.

Faith and it’s impact on the arts informs much of Turner’s work, including Hungry For Heaven: Rock ‘n’ Roll and the Search for Redemption, Amazing Grace: The Story of America’s Most Beloved Song and Imagine: A Vision for Christians and the Arts.

Turner was originally asked to write about the gospel according to rock ‘n’ roll, but chose to focus on the Beatles instead. Speaking from his home in London, he explains, “I had done Hungry for Heaven a few years ago. I’d looked into the Pentecostal roots of Elvis and Jerry Lee [Lewis] and Carl Perkins, and the Baptist roots of Little Richard and Chuck Berry. I’d followed all the way through and looked at the religious, or spiritual influences on rock ‘n’ roll, and the Beatles were just a minor part of it. If I did the gospel according to rock ‘n’ roll I’d be covering pretty much the same territory, [so] it made more sense to focus on an individual band.”

Turner sheds light on an area that until now has rarely been explored. Most writers overlook this angle altogether. “They would see that kind of religious influence as entirely incidental, so they don’t really pay it much attention. If they do, it’s usually glossed over in a paragraph. For example, John Lennon’s involvement with the church; attending Sunday School, being confirmed, and being in the choir. It’s never really gone into in depth. Yet not only does it provide the theological background that he had, but also quite a large part of his musical background, because he learned about singing in unison and harmony, background to hymns, and things which would have played quite a big part in preparing him to be a songwriter.”

No band impacted 20th century culture quite like the Beatles.

“John once gave this analogy – where he said their generation was like a ship, and the Beatles happened to be up in the crow’s nest. They had better vision, they could see what was coming up ahead, and they could shout down to the crew and the passengers, and tell them what was coming up.”

Numerous factors contributed to creating such a unique scenario.

As pop superstars, “they would get introduced to things a lot earlier than anybody else in their generation. Because – as with any celebrity – there will always be people trying to introduce you to a new idea, a new philosophy, a new book, a new film. And at that time not many people were going to L.A., and to Thailand, or Japan or Australia. So at a young age they’d seen quite a bit of the world.

“A lot of the things that they get the credit for pioneering – LSD, and Hindu philosophy through Transcendental Meditation, for example – were things that had been in the air for a long time, going back to the late 19th century. If you look at the writers that took a very similar approach; people like Aldous Huxley or Christopher Isherwood, or even the Beat writers; Alan Watts, for example, their audience was a lot smaller. But here you had people going the same path, but they grabbed an audience by doing pop music, and selling millions of records.”

Their audience was incredibly loyal – and spanned the globe.

“They had a very impressionable audience. People though that anything the Beatles were into must be good, because they were producing such good work. They were cultural leaders; if you saw a photograph of them, and there was a book in the background, or any kind of clues to this lifestyle they were leading, you’d latch onto it.

And suddenly there were people like me, who knew nothing about psychedelic drugs, who knew nothing about Transcendental Meditation. I didn’t know what a Guru was. I was a teenager, and I sent away for the Maharishi’s book. In 1963 I would have been interested in the Cuban-heeled boots. In 1965 I would have been interested in the flowered shirts. And the Maharishi was just another accessory as far I was concerned.

For many, it was as if the Beatles were in possession of a deeper truth. They would await each release, ready for further revelations.

For many, it was as if the Beatles were in possession of a deeper truth. They would await each release, ready for further revelations.

“We did listen to them as if they’d got access to some sort of knowledge that we didn’t have…because up to that time there was a fairly settled culture, and people were quite heavily dominated by Christian thinking. Even something like keeping Sunday special; it was just something everybody did. And the Beatles were part of the first generation to challenge the supremacy of that world-view. To give the impression that there were loads of world-views on offer – you could sort of pick and mix, and they were out there exploring.”

Turner cites ‘Penny Lane’ as “a song that exemplified this new consciousness – just a very magical song. It’s about a non-descript area of Liverpool, but Paul makes it seem like paradise. All the normal events are injected with this magic, and it has this kind of sheen on it. That’s really the way they communicated their view of life. It was integrated into their work. It wasn’t heavy-handed; it just seemed like this was a diary of their life. And it was a life that a lot of people would have liked to have been living.

“Each album seemed to be a real breakthrough. Even in hindsight, you can see they really were breakthroughs, and these were happening at one a year.” Everything had significance: ‘The way the tracks were sequenced, the cover art, whether the lyrics were included, and the interviews at the time that the albums came out…so when I think of a particular Beatles album…”

Turner notes the so-called ‘White Album’ (actually titled simply The Beatles) as an example, stating: “…a lot of it was written in India. You knew everything about where they had come from, and the contrasts between the White Album and Sgt Peppers and Magical Mystery Tour – why it had a plain white cover, what it was a reaction against. All that stuff was part of how we received the songs.”

Turner notes the so-called ‘White Album’ (actually titled simply The Beatles) as an example, stating: “…a lot of it was written in India. You knew everything about where they had come from, and the contrasts between the White Album and Sgt Peppers and Magical Mystery Tour – why it had a plain white cover, what it was a reaction against. All that stuff was part of how we received the songs.”

“They were streets ahead of their nearest rivals. But their rivals – people like the Stones, Dylan, the Who or Brian Wilson – they’d want to get the pressings of these things as soon as they were made, in order to hear them to see what you were up against. And that spurred them onto greater heights.”

The Beatles first came together via a shared passion for rock ‘n’ roll. At the time, the music was only a few years old, and still frowned upon by the older generation. “It was often covered as being almost something like the hula-hoop. In Melody Maker they would be saying is the cha-cha going to be next? They thought rock n’ roll was [a passing fad] There’d been these different dance trends, like the mambo, and they thought rock ‘n’ roll was just like that. It’s just a new thing, it would probably last a year or two and then we’d get [back] with the big dance band music.”

A second U.S. originated phenomenon – the Beat Generation – provided a more cerebral inspiration. Adopting the movement’s anti-conformist philosophy was a major turning point in their development.

“I think it was. If you look back through the literary magazine that was done by the University in Liverpool at the time, the Beat writers were given a fair bit of space – [Allen] Ginsberg and [Jack] Kerouac and people like that – and then there were the British imitators as well. It was a movement that was definitely in the air at the time. I know that John read Beat literature. Paul did as well.”

In many respects, the Beatles’ spiritual journey simply followed the path the Beats had already trod: “The Beats went through a similar transition, often coming from religious backgrounds themselves – like Jack Kerouac – and then getting into Existential thought, becoming interested in European Philosophism, then getting into either Buddhism or Hinduism or both, and experimenting with drugs. That was a very similar path they took, but a decade or more earlier.”

The Beats were certainly aware of the band. “It’s interesting – there was a letter from Jack Kerouac, where he mentioned the Beatles, and said ‘You don’t think it’s an accident that the first four letters of their name is Beat?’ Although he wasn’t a great enthusiast for the counter-culture in the sixties, or for rock ‘n’ roll funny enough, he saw a connection.

“I don’t think Gregory Corso was [a fan]. But [Allan] Ginsberg was. He went to see the Beatles in Portland, Oregon, and wrote a poem about them. I think he could really see that they were carrying the flame of a lot of what the Beat Generation had begun.”

Ginsberg became friends with the band, and appeared on John Lennon’s ‘Give Peace A Chance’ single in 1969. Ginsberg’s final recording – Ballad of the Skeletons (1996) – was a duet with McCartney.

While America provided inspiration via rock ‘n’ roll and the Beats, the Beatles couldn’t have happened at any other place or era than Britain in the sixties.

Marked by almost constant change, the decade began with the abolishment of National Service (compulsory enlistment in the military), and the arrival of the birth control pill.

“There had been a kind of loosening of the mortar before they’d come along; there were so many social trends that coincided.

“Everybody was doing two years of National Service from 18-20, and that introduced a certain level of conformity, trying to control people to a certain extent. Two years of subjecting themselves to authority; polishing their boots, obeying people, and having their hair cut short.” Norman Chapman, who drummed for the group before Pete Best – had to leave the band after he was called up in the summer of 1960.

National Service was abolished on December 31, 1960. “And suddenly this generation was the first not to have that hanging around. They could remain young for a lot longer. There wasn’t that delineation between ‘now you’re a child-now you go in the army-now you’re an adult.’ Childhood was prolonged right through your twenties. And people started to dress like children; we had long, floppy hair…and were dressing pretty much like kids dressed at twelve when they were twenty two or twenty five. And the girls, similarly – short dresses, dungarees – very much like children’s clothes.

“And of course the pill became available in Britain just about the time the Beatles detail started. So you were singing to a generation that was experiencing sexuality in a different way to their parents and grandparents. Even though similar things had gone on, it was now given much more sort of official approval.”

The Beatles were befriended by a group of young existentialists during their early trips to Hamburg. Practicing a philosophy that went hand in hand with the Beat movement, the ‘Exis,’ as they called themselves, took their look from French cinema, including wearing their hair long and combed forward – a radical idea at the time, and one which they convinced the band to adopt.

Back home, they took inspiration from two divergent sources: the ‘angry young man’ movement then the rage in British literature and film, and – conversely – the Goon Show, a ground-breaking comedy series broadcast by BBC Radio from 1951-1960.

Featuring Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe and Spike Milligan, the Goons’ surreal brand of humor never found an audience outside of Britain, but the Beatles instinctively incorporated the Goons’ approach, offering a fresh, albeit cheeky attitude that endeared them to the press and public alike.

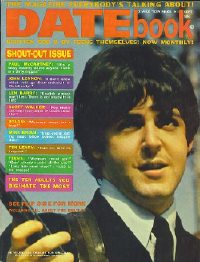

The single most controversial episode involving the Beatles and religion was John Lennon’s 1966 quote – taken out of context – that the Beatles were bigger than Jesus.

The single most controversial episode involving the Beatles and religion was John Lennon’s 1966 quote – taken out of context – that the Beatles were bigger than Jesus.

Datebook magazine ran the story that caused the controversy in America.

Located above Lennon on the magazine’s cover was a quote from Paul that used the term ‘nigger.’ “That’s far more offensive…he was obviously speaking up for the black people, where you’re made to feel like a ‘nigger.’ If they had got angry about Paul’s quote it wouldn’t have been because he used the word – it would have been because he was defending black people against white supremacy.”

Ironically, McCartney’s comments went unnoticed, but the Ku Klux Klan issued death threats in response to Lennon’s quote. Turner believes the Klan were more of a nuisance than any sort of bonafide threat; “I’ve seen footage of one of the Klan guys, and there seems to be a smirk on his face, and you wonder how much of it was just dressing up in fancy clothes, and how much was a serious threat.

“I know the band worried; …somebody threw a firecracker at the concert in Memphis, and they heard this crack and they really did worry that somebody might have taken a shot at them.”

Turner interviewed Doug Layton, the Birmingham, Alabama DJ, who along with his on air partner had called for a boycott of Beatles records. “They had a reputation for being straight talking and challenging City Hall and things like that. I was surprised to find that he wasn’t a particularly religious person himself. They just thought that the Beatles were getting too big for their boots – they need taking down a peg, and this just happened to be the thing that would do it.”

The boycott quickly escalated into call for mass public burnings of all Beatles records, magazines and souvenirs.

“This [was] the only story they ever did that really had an international effect. I think they regretted it in the end, because when Layton dies, that’s surely going to be the headline in his obituary.”

Lennon’s quote may have been taken out of context, but for many people, the Beatles really were more popular that Christ. Turner describes girls in the audience approaching a state of abandon similar to a Pentecostal experience, and cripples lining up hoping to be cured.

And some were healed.

Rather than ascribing such formidable powers to the band, it’s likely these incidents were similar to the dubious healing ‘miracles’ phony preachers often take credit for. “It could be; if it was psychosomatic. Which I’m sure it is with a lot of these preachers; somebody goes up with the expectation of something happening and they just slap them on the forehead.”

Drugs played a significant role throughout the Beatles’ career. They’d indulged in a wide variety of pills since their days in Hamburg, and Bob Dylan introduced them to marijuana in 1964. John and George first tried LSD in 1965, with Ringo and Paul following soon after.

After that, everything changed. “Hallucinogenic drugs without a doubt produced the crucial turning point.” The mop-top image, already on it’s way out, was truly dead.

Instead of witty retorts, the answer they would give – the response to every question – was ‘Love.’ “That came after the experiences with LSD. And it seems a lot of people felt overwhelmed by some universal feeling of love towards everybody. Almost like indiscriminate love. I don’t know whether that was love that would have turned into any form of sacrifice. It was kind of like a warm feeling, if you like. And that’s precisely what happened to John and George – particularly George – after the first time they took LSD. They got this sort of warmth inside towards everybody, but as I say, the outworking of that is a completely different thing, because you can feel benevolent towards mankind, but not particularly well disposed towards your next door neighbor.”

Lennon estimated he had taken at least 1,000 trips, and Paul claimed to be ‘deeply committed to the possibilities of LSD as a universal cure-all.’

Eventually, the psychedelic experiences were supplanted by explorations into Eastern ways of thinking.

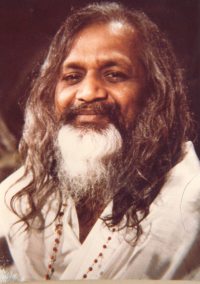

In 1967 they discovered the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and Transcendental Meditation. Enthralled by his promise to create Heaven on earth, they visited India, where the Maharishi would conduct daily lectures. In addition to espousing the benefits of TM, he would frequently criticize Christianity.

In 1967 they discovered the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and Transcendental Meditation. Enthralled by his promise to create Heaven on earth, they visited India, where the Maharishi would conduct daily lectures. In addition to espousing the benefits of TM, he would frequently criticize Christianity.

“I think he was pretty shrewd, and realized that the majority of the people who were coming to his camp at that time had come from Christian backgrounds, so I think he on the one hand wanted to say ‘TM is not a religion, it can be part and parcel of your religious life, you don’t have to give anything up.’ But then there was that kind of slightly undermining thing going on at the same time.

“He seemed very keen to declare that it was a science, and he had this scientific background. In fact his book was called The Science Of Living And The Art Of Being. Turner laughs at his attempts to understand the Yogi’s writings. “I read it when I was about 18 and I made notes in the margins, and I thought [years later], well, now I’m a bit older, maybe I’ll understand.” It was as mystifying as ever. “A lot of it is quite incomprehensible.

The flirtation with TM ended almost as quickly as it had begun.

“They were such great advocates, and had gone to India and that got enormous coverage around the world. Then things came to a bad end at the camp, I think partly because the Maharishi saw the commercial possibilities of getting the Beatles involved in different projects, and the Beatles were not wanting to be used in that way. And they started to badmouth him a bit, particularly John, who I never think was 100% on board anyway.”

Over the years Paul has referred positively to the experience – which is typical of his personality – but Lennon remained angry. “I’m sure that’s because of their different backgrounds. I think John was always aware there was a hole in his life, and if something came in and supported him for awhile, and then he found it didn’t measure up, he could turn quite bitter. I suppose just that sense of rejection that he felt deeply about his father – that his father had left him – I think he was always worried that people were going to leave him. Or let him down or not live up to their word.”

Lennon expressed his resentment in song, including ‘Sexy Sadie,’ – which was originally entitled ‘Maharishi,’- and ‘The Maharishi Song.’ Never officially released, the lyric leaves little doubt as to his feelings; ‘Me, I took it for real…I felt like dying, crying, and committing suicide…And I thought what the hell’s this got to do with what that silly little man’s talking about? But he did charm me in a way…telling stories of heaven, as if he knew. But you could never pin him down…He looked Holy – but he was a sex maniac…”

Over the course of their career the Beatles espoused a variety of philosophies. What does Turner consider they got right?

“I think they were right in observing that there was a problem. Take ‘Nowhere Man.’ That’s almost a distillation of what they saw as the problem; ‘He’s a real Nowhere Man…doesn’t have a point of view, knows not where he’s going to.’

“They’d achieved fame at a very early age, and they got all the money, all the fame. They got everything that the secular world would say should satisfy you. And it hadn’t satisfied them in the way that they thought it would, and they started asking these fairly profound questions.

“But I think where they diverged from, well – any orthodox Christian faith certainly – in Christian faith you’d say ‘what you need is a change of heart,’ and they kind of went in the direction of saying ‘what you need is a change of mind.’ More specifically, a change of consciousness.

“They were saying it was all in the head, basically, which is George’s line in the Yellow Submarine film; he keeps wandering around mumbling ‘it’s all in the mind.’ And that was really the conclusion they came to, I think. That it was all in the mind. It was all in the consciousness. So all their remedies were to do with changing your consciousness, and that started with pot and went to LSD and then techniques of meditation and other things that they considered were all to do with how you could alter your consciousness. So I don’t think they believed in a real spiritual reality or realm outside themselves. It was all within the head. You’ve got to change your head, as they said.”

“Certainly John was open to almost anything that would tinker with his consciousness, and give him an enlarged experience. At one time he contemplated trepanning: having a hole bored into your head…”

The brainchild of a failed medical student, trepanning involved drilling a small hole directly into the skull. In theory, the process would allow increased flow of blood and oxygen to the brain, which in turn; “…would make you high, sort of permanently high.

“There were different things like that he would try, all to do with ways of enlarging your consciousness, and therefore your appreciation of the outside world.

When an interviewer asked him ‘do you believe in God or the spiritual world?’ he said ‘Yes, I’ve had many experiences of other states of consciousness through dieting, through meditation, and he listed a whole load of things. So he was very interested in altered states.”

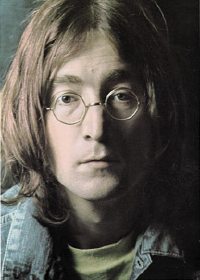

JOHN

In many ways it appeared as if he was trying to fill what Pascal referred to as a ‘God-shaped hole.’

In many ways it appeared as if he was trying to fill what Pascal referred to as a ‘God-shaped hole.’

Of the four, John had the most familiarity with the church. Significantly, he first met Paul while performing at a function for St. Peter’s Parish Church, where he had been involved in Bible study class, Sunday school and choir.

Church had been a regular part of his life until the death of his mother. After that, his outlook darkened considerably. On the rare occasion when he did attend, according to friends he would take money from the collection and buy beer.

Lennon shared a spiritual curiosity similar to that of his hero, Elvis Presley. Both were fascinated with elements of Christianity, astrology, psychics and various New Age teachings. “Maybe for the same reason; they both had some sort of Sunday School grounding. And I don’t think either of them really ‘shook’ Jesus off, if you like. I don’t think Elvis tried to in the sense that John tried to. I think John would have liked to have got rid the influence of Jesus, but he kept coming back. It reminds me of Flanner O’Conner, who talked about the south being ‘Christ haunted.’ There seemed to be a way in which he was kind of haunted by Christ. Why would he say we’re more popular than Jesus? It could have been more popular than Kennedy, or more popular than [whomever]. I think Jesus was kind of there all the time, and he would become quite animated in talking about Jesus.

“In his final interviews he certainly talked about reading the Bible, going back to it and understanding more than he’d ever understood before, particularly the parables of Jesus. There were allusions to different parts of scripture which showed that he’d had a fairly good grounding in Sunday School. He seemed well aware of the main doctrines and stories, so he could say something like; ‘where two or three were gathered,’ and that’s an allusion anybody familiar with the Bible would pick up, but if you weren’t it would just slip by you.”

“In his final interviews he certainly talked about reading the Bible, going back to it and understanding more than he’d ever understood before, particularly the parables of Jesus. There were allusions to different parts of scripture which showed that he’d had a fairly good grounding in Sunday School. He seemed well aware of the main doctrines and stories, so he could say something like; ‘where two or three were gathered,’ and that’s an allusion anybody familiar with the Bible would pick up, but if you weren’t it would just slip by you.”

In the late seventies Lennon had a short-lived flirtation with Christianity. The story has been covered to some extent elsewhere, but Turner managed to track down more information, including correspondence between Lennon and televangelist Oral Roberts.

“That was strange. There were a couple of books came out maybe four or five years ago, about John’s stay in America and they were based on these diaries that had been stolen by Fredrick Seaman, who’d worked for Yoko. These guys couldn’t quote directly from the diaries, but they’d obviously read them and knew them almost word for word. It was clear from that that he’d got interested in Evangelists on television, and gone through this kind of brief conversion period. I wrote this up for Christianity Today, and then that story must have been carried in a Washington newspaper, and then I had a letter come to me, forwarded on to me by this Washington newspaper, from a guy who’s actually in prison, who said that he’d been a student at Oral Roberts University. He said ‘I’m surprised you didn’t mention Oral Roberts, because I can remember being at a morning assembly, and Roberts said he’d just come off the phone with John.’ At least that’s how he remembered it. So I filed this letter, and when I came to do this book I got in touch with Oral Roberts University, and they looked through transcripts of the morning assemblies, and found this one where he’d actually read out the text from John Lennon in the morning assembly.”

In his reply, Roberts refrained from the more over-the-top statements he was famous for. “He seemed fairly balanced about it. He says that he enjoyed the Beatles when they came to America, and blah blah blah. I was surprised, because he’s not one of my favorite personalities. But he seemed to have tackled it fairly sensitively. I got the impression there’d just been this the one letter from John, and maybe Oral Roberts had written back a couple of times, sent a couple of his books and that was probably the end of the affair.

“I was quite surprised that John would [choose Oral] – you’d think that if he was going to respond to any type of Christian that it wouldn’t have been a sort of primetime televangelist, but then again who’s to tell with John, because he got involved in so many things. Maybe he just liked the directness and the confidence that these people had.”

Turner checked out other possible sources. “I contacted the Billy Graham organization to see if he’d had any contact with him, but they had no record of it. One of the books said that he’d been quite entranced by Pat Robertson on the 700 Club, and had called their prayer line, but I was in touch with 700 Club and again, they had no record, but then, why would they have if he’s just a guy calling in for advice or prayer?”

Lennon never mentioned the incident to the press, but – typically – one of his songs alluded to the experience; “There was this song he did called ‘You Saved My Soul’ which has never been released. There’s a reference to almost being seduced by a television evangelist, but being saved; ‘you saved my soul,’ meaning Yoko saved my soul by keeping me away from the evangelists. But that’s an allusion rather than direct reference, and only when you know that background does it make much sense. That’s the only thing I came across where he referred to it.”

Lennon never mentioned the incident to the press, but – typically – one of his songs alluded to the experience; “There was this song he did called ‘You Saved My Soul’ which has never been released. There’s a reference to almost being seduced by a television evangelist, but being saved; ‘you saved my soul,’ meaning Yoko saved my soul by keeping me away from the evangelists. But that’s an allusion rather than direct reference, and only when you know that background does it make much sense. That’s the only thing I came across where he referred to it.”

Throughout his life Lennon would oscillate from savior to savior, invariably falling out with those who couldn’t meet his needs. “On the one hand he seemed the guy that would dismiss everything and he wouldn’t believe anything without proof. But on the other hand he seemed the most gullible of the Beatles. Long after he’d sung ‘Imagine’ – which absolutely rejects all forms of superstition or the spiritual world – even after that, he got into loads of things that the average person in the street would find completely cranky. Like going around the world – you must go around the world in a westerly direction, and actually changing flight plans to follow these things, and believing numerology and the significance of the number nine. His life seemed in a way riddled by superstition.

“Yet for somebody seen as iconoclastic and defiant of authority, he was actually completely under Yoko’s authority, or the authority of the astrologer, the psychic, the number nine, whatever it was. He gave an impression of freedom, but seemed to be far from free.”

‘God,’ a song from his first solo album, lists everything he no longer believes in –including magic, the I-Ching, the Bible, Tarot, Jesus, Buddha and Yoga – before concluding that now he just believes in ‘Yoko and me.’

‘God,’ a song from his first solo album, lists everything he no longer believes in –including magic, the I-Ching, the Bible, Tarot, Jesus, Buddha and Yoga – before concluding that now he just believes in ‘Yoko and me.’

“Because of his particular background he was really ripe for a savior figure, whether it was a male figure like the Maharishi, or in her case, a female figure.

“He became very devoted to her, like he wanted to be absorbed in her, and her in him. One of the early albums [Sometime In New York City] had his face morphing into her face, all around the circle of the center of the record, so when the record was spinning around it would look like one face. Or they would do things like have one side of her face matched with one side of his face. There was a total absorption in each other. I suppose theologically it’s almost like Christ and the church, that kind of morphing together so they would be one person.”

PAUL

As songwriters, Lennon and McCartney brought out the best in each other. After the band broke up, McCartney’s syrupy side took over, and Lennon became politicized to the point of alienating most of his audience. “They sort of curbed each other’s excesses. I think they admired each other, obviously respected each other, but there was a slight grudge between them because they were such complete opposites in almost every way.

As songwriters, Lennon and McCartney brought out the best in each other. After the band broke up, McCartney’s syrupy side took over, and Lennon became politicized to the point of alienating most of his audience. “They sort of curbed each other’s excesses. I think they admired each other, obviously respected each other, but there was a slight grudge between them because they were such complete opposites in almost every way.

“Paul had the very sort of settled background, and he was much happier to be in show business, and he was the diplomatic one. Whereas John’s background was much more screwed up, and he was much less sure of himself. More aware that he wasn’t the good looking face in the band. Paul was always very confident in the way he looked.

“Paul had the very sort of settled background, and he was much happier to be in show business, and he was the diplomatic one. Whereas John’s background was much more screwed up, and he was much less sure of himself. More aware that he wasn’t the good looking face in the band. Paul was always very confident in the way he looked.

“All of Paul’s love songs were very confident; ‘we can work it out.’ You always know it’s going to go his way. Whereas John is the opposite – always bracing himself for disappointment; always waiting for the blow to descend.

“I think John would have made Paul a lot more poetic and artistic, and Paul probably made John a lot more lively and added a little bit of showbiz pizzazz. Otherwise, [John] could be quite melancholy. Whereas Paul was very jaunty, and enjoyed being a pop star.”

McCartney’s ‘Let It Be’ is occasionally sung in churches. “Paul called it a ‘quasi-religious’ song. It’s based on a dream he had about his own mother, who was called Mary, and who was, incidentally, a Catholic. He would be very aware of the resonance of saying ‘Mother Mary.’ And it does bear some comparisons with not only things Mary said about ‘let it be done to me’ in the Magnificat, but also Buddhist and Hindu teachings about letting go. So it definitely does – as Paul says – have a quasi-religious feel about it. But not tied to any particular religion. Which is probably why people like it.”

GEORGE

George was known as the ‘spiritual Beatle.’

George was known as the ‘spiritual Beatle.’

“He was always for getting real, and ignoring the fantasy side of life. The glitz and the glamour didn’t really interest him. I think of all the quotes in the book, some of his are the most profound, and the ones I’m sure that Christians would most identify with. Because he said something like the search for everything can go on, but the search for God is the most important.”

“There was some material that Art Unger – the publisher of Datebook – had in his archives, interviews he had done with the Beatles, and one of them was with George about  religion. George was saying that one of the problems he first had with Indian religion was finding a place for Jesus in it; he couldn’t see how Jesus could fit in. I was quite of surprised by that; he’d always been so hostile towards Catholicism because of his own experience of it, but seemed to have some kind of respect for Jesus.”

religion. George was saying that one of the problems he first had with Indian religion was finding a place for Jesus in it; he couldn’t see how Jesus could fit in. I was quite of surprised by that; he’d always been so hostile towards Catholicism because of his own experience of it, but seemed to have some kind of respect for Jesus.”

When I spoke with Roger McGuinn last year he recounted a 1986 visit to George’s home. They discussed Christianity, and George claimed if getting to God meant accepting Jesus, then he rejected him. Turner was unaware of the exchange, but wasn’t surprised.

“I think it was the exclusivity that he couldn’t handle. The impression I got was that all religions were cool, but any religion that claims exclusivity he wouldn’t go for.

“George never subscribed to any particular religion, even though Krishna consciousness was the one that he seemed to put his name to more than anything. He did claim that he didn’t belong to the Krishna movement. He was reluctant to say that this was his religion. I think he wouldn’t have minded a religion that had bit of Buddha, a bit of Krishna, and a bit of Jesus…maybe a bit of Mohammed as well.”

RINGO

Ringo has been a member of Alcoholics Anonymous for quite a few years. Part of that group’s formula for recovery is the acceptance of a ‘higher power.’

Ringo has been a member of Alcoholics Anonymous for quite a few years. Part of that group’s formula for recovery is the acceptance of a ‘higher power.’

“Even in the Beatles Anthology he talks about being much more spiritual these days and things like that. He seems to place a great priority on the spiritual, if you like, and he does talk a lot about love.

“He’s a great believer that all the stuff that they talked about – love and peace – in the sixties was really good, and he’s proud of that as an achievement and wants to keep it alive. There seems to be a sentimental side to Ringo and also a soft side.”

“He’s a great believer that all the stuff that they talked about – love and peace – in the sixties was really good, and he’s proud of that as an achievement and wants to keep it alive. There seems to be a sentimental side to Ringo and also a soft side.”

Turner mentions a recent Starr composition ‘Oh My Lord’ which appears on his latest studio album (Choose Love), ‘I thought it might be a Krishna-type song but it’s a gospel song, basically saying ‘I need you, Lord.’ So I don’t know if the A.A. experience has pushed him into that direction, which in a sense would be reconnecting him with his own roots; going to Sunday School and evangelical church in Liverpool, or whether it’s something else. I’d love to find out.”

After he became a believer, Turner was one of the first voices from the church to contend that rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t dangerous. He especially credits the Beatles for being a positive influence.

“I think because I’d grown up listening to the Beatles, I thought: ‘This is the way you incorporate what you believe into what you do. That’s what they’re doing. Why can’t I do it?’

“So when I started writing poetry I thought: ‘That’s what I want to do, I just want to be like a normal poet, but I’ll just incorporate what I believe, like the Beatles incorporate, like the Stones incorporate what they believe in their songs.”

“It wasn’t a big battle for me. I thought surely it’s gotta be like that.”

It’s almost as if Turner was predestined to write a book on the Beatles and their spiritual journey. He grew up an ardent follower of the band while joining his family for church every week. At one point he attended a Billy Graham Crusade.

“My parents are Christians, and I’d gone along – I remember in ’66 going to Earl’s Court, and actually seeing him. A friend of mine came for a sort of laugh, and then he went forward, and it was embarrassing for me.” He chuckles “But it was like having a foot in both camps, because I was in the family and I would go along to church because is was safer to go along than not to go along. And yet I was becoming more interested in music, and they just seemed to be two worlds that would never meet.”

For a long time, the church held little appeal.

“I couldn’t imagine being like most of the people that I knew that were Christians.

It seemed to be a cultural thing. I just couldn’t imagine wanting to dress like them, be like them, have their interests. And that seemed to be quite a big obstacle to me at the time.

“There seemed to be lots of examples of people who looked really kind of groovy, and were into all sorts of wonderful things, and then they became Christians, and became all sort of boring.

“Sometimes there would be like a hippy, and he’d become a Christian, and then he’d be wearing a gray suit with a tie. And this was used as an illustration of the transformation in his life…saying that once he’d been a bohemian, but look at him now, he’s middle class like the rest of us. And this is what Jesus could do in your life. So I just found that a bit of a strain.”

“In 1970, I remember thinking when I heard the song ‘Woodstock’ that Joni Mitchell wrote on the Crosby, Stills Nash and Young album – and it’s got that line about ‘we’ve got to get back to the garden.’ I thought it was amazing that they were using a biblical image, and why aren’t Christians involved in this debate? They’re not really in the debate; they’re playing Jesus Rock in churches in California, and it was like a side show, really. Readers of Rolling Stone would have known nothing about Love Song or Country Faith or all these Jesus Rock bands. Most of the music tended to emulate what was going in the secular business, but was always a bit behind and not as good. So there were some things that I struggled with before I became a Christian.”

In the end, the Beatles were an absolutely unique phenomenon. Turner wonders how McCartney and Starr perceive their experiences today; “Because I don’t think you can look at the Beatles’ success and say it was all to do with chord changes. I don’t think the cultural effect can explained simply by [saying] ‘well, they were good tunes.’ There was something going on at a much deeper level, and they were right in the driving seat. It must have amazed them at the time. As they’ve had thirty odd years to reflect on it, I think they must wonder what happened and why it happened.”

In the end, the Beatles were an absolutely unique phenomenon. Turner wonders how McCartney and Starr perceive their experiences today; “Because I don’t think you can look at the Beatles’ success and say it was all to do with chord changes. I don’t think the cultural effect can explained simply by [saying] ‘well, they were good tunes.’ There was something going on at a much deeper level, and they were right in the driving seat. It must have amazed them at the time. As they’ve had thirty odd years to reflect on it, I think they must wonder what happened and why it happened.”

It was much more than the music. “The Beatles “cause(d) the whole generation to band together, and go through this sort of thought process about who we are, where do we come from, for what ends were we created, and things like that. All these things seemed to come together along with the music: the drug culture, counter-culture, and changes in recording technology. Just everything seemed to happen at the same time. It impacted everyone.” He begins to laugh. “Well, I keep saying everyone, but it seemed to be my generation it impacted, anyway.”

© John Cody 2007