“MAY the Baby Jesus open your mind and shut your mouth.”

Discerning fans with long memories will recall that delightful insight from the inside sleeve of Captain Beefheart’s classic 1967 Safe as Milk LP.

However, the phrase likely came from the entrance to San Francisco’s fabled Avalon Ballroom (where the good Captain and many other key acts performed), and implied there was far more going on inside than simply dancing.

In fact, for a few years, things were decidedly different in the city.

Remembered – and often lampooned – for the mid-60s hippie subculture it spawned, the city was ground zero for a seismic cultural change that’s still being felt today.

At its core was a questioning of all that had come before, and a search for the true meaning of love. The degree to which it succeeded or failed remains an ongoing debate; but, to paraphrase Eric Burdon’s ‘San Franciscan Nights’; it was a time when walls moved – and minds did, too.

Much of the music produced during the era addressed spiritual concerns. Some was undoubtedly drug-induced; nonetheless, these were areas pop music had rarely touched upon.

‘Who Am I?’ by Country Joe & the Fish revealed a yearning that went beyond anything drugs could satisfy; and Quicksilver Messenger Service’s ‘Pride of Man’ was rife with Old Testament imagery.

On Volunteers, an album which called for revolution in the street, The Jefferson Airplane followed the title track with ‘Good Shepherd,’ a traditional gospel ballad. Guitarist Jorma Kaukonen and bassist Jack Cassidy would go on to perform more than a dozen gospel songs, mostly by Rev. Gary Davis, in their offshoot band, Hot Tuna.

That none of the above are included on Love is the Song We Sing – a new collection from Rhino documenting the era – underscores the wealth of material available to the compilers.

That none of the above are included on Love is the Song We Sing – a new collection from Rhino documenting the era – underscores the wealth of material available to the compilers.

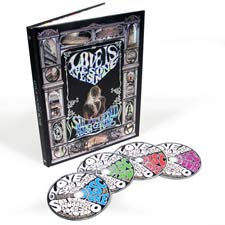

Covering the years 1965 – 1970, the four discs come encased inside a beautiful 11” x 9” hardcover book, upon which the Avalon’s ‘Baby Jesus’ quote is front and centre. Cleverly, it’s only discernable when held at certain angles.

The set takes its title from the lyric to ‘Let’s Get Together,’ one of the era’s defining anthems. Two performances bookend the package: the composer, Dino Valenti, starts things off with an acoustic demo; and the Youngbloods end the proceedings with what is widely considered the definitive rendition of the song.

Released in 1967 as ‘Get Together,’ their version became a top 10 hit two years later, after the International Council of Christians and Jews used it in a series of public service ads.

All the requisite names – Country Joe, The Airplane, Quicksilver, Santana, Steve Miller, Janis Joplin, Moby Grape – are well represented, as are FM radio staples like ‘White Bird’ by It’s a Beautiful Day.

The music reached far beyond the underground. There are plenty of pop hits: from the Beau Brummels’ ‘Don’t Talk to Strangers’ (one of the earliest American responses to Beatlemania) and the folk rock of We Five on ‘You Were on My Mind,’ to Count Five’s garage rock staple ‘Psychotic Reaction’ and Blue Cheer’s proto-metal take on ‘Summertime Blues.’

Christian rock pioneer Larry Norman shows up singing with People, who hailed from San Jose. Norman would leave soon after their one hit – a cover of the Zombie’s ‘I Love You’ – due to religious issues. Ironically, it wasn’t so much his faith, as the fact that the majority of the band had become ardent Scientologists – and wanted the rest to convert.

When the band were inducted into the San Jose Hall of Fame last October, the members still held to their individual faiths, with one notable exception: drummer Denny Fridkin had recently become a Christian, and credited Norman’s example as a primary reason for his conversion.

While many of the acts went on to become household names, it’s the lesser-known outfits which will interest listeners already familiar with the era.

Obscurities by Mad River, the Mystery Trend, and the curiously titled ‘My Buddy Sin’ by the Stained Glass – who would change their name to Christian Rapid – show that there was plenty of first-rate material which didn’t make it to radio.

The Grateful Dead appear three times: with the opening track from their 1967 self-titled debut ‘The Golden Road (to Ultimate Devotion)’; the single version of their in-concert epic ‘Dark Star’; and ‘I Can’t Come Down’ – a track from 1965, when they were known as the Warlocks.

The Grateful Dead appear three times: with the opening track from their 1967 self-titled debut ‘The Golden Road (to Ultimate Devotion)’; the single version of their in-concert epic ‘Dark Star’; and ‘I Can’t Come Down’ – a track from 1965, when they were known as the Warlocks.

Even at that early stage, they were proclaiming a new reality: “I can’t come down, I’ve been set free / Who you are and what you do / don’t make no difference to me.”

They made their reputation as psychedelic pioneers, but the Dead’s roots were in folk and bluegrass music, and their songbook contained a number of gospel standards – including ‘We Bid You Goodnight,’ as well as Rev. Gary Davis’ ‘Samson and Delilah’ and ‘Death don’t have No Mercy.’

Many of their own songs employed biblical imagery. Characters from scripture – Jehosophat, Ahab, Cain and Abel, the prophet Ezekiel, Abraham – show up, sometimes repeatedly; and lyricist Robert Hunter frequently referenced the Psalms.

Numbers such as ‘My Brother Esau,’ ‘Attics of My Life’ and ‘The Wheel’ (‘Small wheel turn by the fire and rod / Big wheel turn by the grace of God’) – employed biblical themes; while others, like ‘Estimated Prophet’ and ‘Victim or the Crime,’ took an understanding of theology to fully appreciate.

In fact, there’s easily enough for a Grateful Dead–related Bible study. (Not such a crazy idea: Wharf Rats, a Dead-inspired group for addicts, models itself after the traditional 12-step programs).

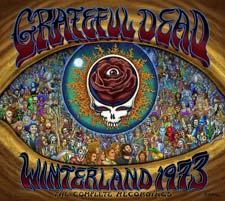

The massive nine-disc set, Winterland 1973: The Com-plete Recordings compiles three nights at the famed San Francisco venue. Like 2005’s Fillmore West 1969: The Complete Recordings – a 10-disc set – the full-length format allows the listener to hear the band in its most natural setting.

Typically, the shows included titles that indicate a familiarity with scripture. ‘Wharf Rat,’ ‘Greatest Story Ever Told,’ ‘China Doll,’ ‘One More Saturday Night’ and ‘Ramble on Rose’ all use biblical imagery – as does ‘Weather Report Suite’ which is repeated all three nights.

Touching on a number of styles – rock, country, jazz – with psychedelia and improvisation, the Dead produced an eclectic mixture no other band could match.

The closest comparison to this set might be Miles Davis’ The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965 or The Cellar Door Sessions 1970, each of which documented multiple night engagements at a single venue.

While Davis worked in a totally different genre, both acts shared a passion for change. Refusing to trade on past glories, they instead risked it all every time they went on stage. That there were nights which just didn’t work is a given, but when it came together – as it does here – it was all worth it.

© John Cody 2008