For most musicians, playing comes down to a simple choice. If you’re motivated, you play.

For most musicians, playing comes down to a simple choice. If you’re motivated, you play.

For Linford Detweiler, that was hardly the case.

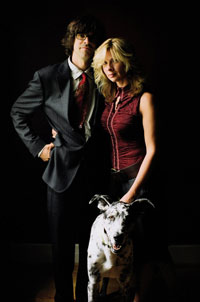

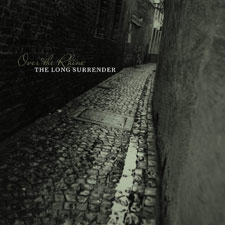

Detweiler and his wife Karin Bergquist – along with a revolving cast of backup musicians – have recorded as Over the Rhine for over 20 years. Their newest effort, The Long Goodbye is arguably the strongest album of their career. I spoke with him recently about a number of subjects, including his rather unique roots.

“I grew up with this background of forbidden music: ‘music is dangerous; be careful.’ So for me, becoming a professional musician was walking a dangerous road.

“Both my parents were raised on Amish farms, and I have lots of stories about the awkward navigation from that sort of culture – one that’s completely removed from the modern world.”

Music and art were considered inherently decadent, which resulted in numerous acts of covert creativity “My father was a very restless child with artistic leanings, and he sketched faces on the side of the white-washed barn with a piece of charcoal. People would gather around these drawings that he had made and recognize themselves.

“They weren’t allowed to have musical instruments; but my uncle Rudy loved music, and he had an acoustic guitar in the haymow. He would sneak into the barn after dark, and play his guitar – and then bury it in the hay. One of his brothers – not knowing it was there – accidentally ran a pitchfork through it one time.”

Other instruments were placed strategically about the farm. “Rudy also hid an accordion under the horse’s manger, and I’ve often drawn the parallel with all this instruments being hidden in the hay: it brings to mind the Christ child in the barn, like a forbidden song.”

He notes that “A cappella singing was allowed, but no accompaniment.” Only one instrument passed muster: the lowly harmonica. “So dad and my uncle played their harmonicas all their lives. That was an exception.”

Eventually, his parents decided to leave the sect. “Dad was very haunted and restless, and we moved around quite a bit. I say now that he was looking for a city not made by human hands, but he wanted to see what was out there. We lived out in Montana for six years and tried different things, but he never quite found his vocation. They were always strong believers and very religious people. They became Mennonite for a while; and dad was a Protestant minister for part of his life.”

Once they left the Amish community, music became a mainstay in the home. “Dad bought a record player, and began to bring home records – everything from Mahalia Jackson to very early Eddy Arnold records to Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony. He didn’t know it was against the rules to play the Mahalia Jackson, Eddy Arnold and Beethoven all in the same evening.

“He also bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder, and made field recordings when we were kids. He’d go out at night and record at the edge of a swamp, or just walk down back roads and make recordings.” My parents knew I loved music, and when they left the Amish, they brought an upright piano into the house.”

It could, on occasion, be cause for consternation. “My grandmother, who was Amish, was coming to visit, and here was this affront – a piano – right in our living room. My sister Grace looked at it carefully, and said ‘Linford, if we cover it up just right, I think she might think it’s a furnace.’

It could, on occasion, be cause for consternation. “My grandmother, who was Amish, was coming to visit, and here was this affront – a piano – right in our living room. My sister Grace looked at it carefully, and said ‘Linford, if we cover it up just right, I think she might think it’s a furnace.’

“My parents loved the fact that I would sit at the piano, and that I took to it quickly and naturally. I went there often as a child to make up my own music. It’s where I learned to read music; my mother would be washing the dishes and she would hand me the hymnal and say ‘Just try to find something that I don’t know; play a hymn.’ And I never recall ever playing a hymn that she didn’t know.”

Playing hymns met with approval; but once he found his own voice, it was a different story. “When I started writing songs, and getting interested in this whole era of the sixties, and what a song could mean in terms of modern culture, then I began to step into something that was so foreign to my parents, there was almost no way to bridge the gap.”

That’s when it got interesting for Linford. “It was extremely exciting for me. And as I differentiated myself from my family, it was not without its concerns and traumas. But shortly before he passed away, my mom and dad came and saw us play. That was one of the first times that they had seen us with the full band. I told a few stories from stage, and said that for years I had been thinking that I would pick up the phone and call my parents and say: ‘Mom and Dad, I’ve got good news. It’s a little bit bittersweet, but the Over The Rhine thing, we’re all done with that now. That chapter has ended, so I’m going to go ahead and get a real job and get back to my real life.’ I always thought I would make that phone call.

“I really believed that when I was starting out. And then I began realizing that I never was; that this is actually what I do. And I told some of our old stories, and tucked that note in there, and then I introduced my parents. Everybody was curious; would my parents be a little shy about being introduced, or have mixed feelings? Well,” he chuckles, “I said my dad’s name, and he practically shot up out of his chair. He was very caught up in what was happening and I think quite proud of what I had accomplished. But culturally, even then, it was a little far out there. So I didn’t pressure them to understand it, or anything like that.”

“It was a complicated relationship,” Detweiler notes. “There were six of us kids, and my dad loomed larger than life in all of us – in all of our lives.”

The old adage of being done with our past, but the past not being done with us, comes to mind; he realizes his father lives on – for good and bad – in his own personality.

“Oh, yeah, absolutely,” he laughs. “He’s still here. But I think he ended well. Dad had a couple of really good final laps, if you want to use the metaphor of running the race. It really ended up well. I feel like he did a lot of healing homework in his last few chapters.”

Given his formative years, it’s hardly a surprise to find a subtle spiritual underpinning to much of Over The Rhine’s oeuvre. “Karin and I both grew up in the church,” Detweiler explains, “and were exposed to gospel music early on. That influence is something we’re quite proud of. The hymnal is a part of our American music heritage that critics sometimes don’t know what to do with, but I firmly believe there could have been no Johnny Cash or Elvis Presley without those hymnals – those hymns they grew up with.

“So when we began writing our own songs, there was a dilemma: do we sign some kind of gospel record deal? It certainly wasn’t out of the question. We knew people that knew people. But we quickly decided we wanted to take our music into the general marketplace, and put it out there with the great songwriters we were discovering. And one of our first big breaks was getting to open some shows for Bob Dylan.”

It was only five or six dates, but the experience would inform all that came after. “We got to stand on the side of the stage with this iconic songwriter who sort of gave us permission vicariously to take what we are doing seriously. And that’s where we felt at home.”

It was only five or six dates, but the experience would inform all that came after. “We got to stand on the side of the stage with this iconic songwriter who sort of gave us permission vicariously to take what we are doing seriously. And that’s where we felt at home.”

They signed with a mainstream label, but never shied away from addressing matters of the spirit. “I’m still very much sorting out the tradition that I came from, my own relationship with God and what I believe. I’m sorting through that, and I want to engage people on that level.

“For me, writing is often very much tangled up in trying to figure out what it is that I care about. What is it that I’m feeling? I’m asking a lot of questions as I go, and for people that want to get into life’s bigger questions, I hope they can find some good questions being asked in my own songs. It’s not so much about saying that ‘this is what I know for sure,’ it’s more about saying ‘I really think I’m learning this. I’ve experienced this small victory that I want to celebrate; how about you? Are you with me one this?’

“G.K. Chesterton said we need priests to remind us that one day we are going to die, but we need a different kind of priest – the poet, the painter, the singer – to remind us that we are not dead yet. That’s what I want to do with my songs; I want to remind people that we are not dead yet.”

They take inspiration from a wide range of sources. “It’s different people at different times, but I’m certainly drawn to fresh language in song – to people that have a lot of facility with language. People like Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Randy Newman.”

The list – as Detweiler readily admits – consists entirely of older artists. “I don’t want to sound curmudgeonly,” he laughs, “but those have been some of the teachers that I discovered as a young songwriter, and they have remained important teachers. I hope I’m continuing to find new teachers. Joe Henry has been an incredible find. I’ve learned a lot from him, both in terms of writing and in terms of being a human being.”

Writers – fiction and non-fiction – are another source of inspiration; “I find myself returning to authors like Annie Dillard, Fredrick Buechner and even Lauren Winner. I like exploring the same terrain as Annie Dillard, whose books function on a lot of different levels; some people appreciate them for the craft, some love her interest in nature – and her unique way of engaging with the natural world – and some are very interested in what she’s exploring spiritually. That’s what I aspire to.”

Sometimes, in spite of a writer’s intent, multiple interpretations can be valid. “That’s the mystery of writing,” Detweiler agrees. “Sometimes listeners will teach us things about our songs. We love that back and forth conversation, and hopefully – because of the different levels – there isn’t just one right or wrong interpretation that neatly summarizes everything.”

Sometimes, in spite of a writer’s intent, multiple interpretations can be valid. “That’s the mystery of writing,” Detweiler agrees. “Sometimes listeners will teach us things about our songs. We love that back and forth conversation, and hopefully – because of the different levels – there isn’t just one right or wrong interpretation that neatly summarizes everything.”

Another enigma is how the artist can at times appear far removed from the art. From Hank Williams to Townes Van Zandt, stories of lives lived in marked contrast to their own lyric are legendary. “I have friends that hung out with Townes quite a bit, and it was a wild ride,” Detweiler notes. “Apparently, he had a lot going on. But I don’t divide the world into the broken and the unbroken. I think we are all flawed, we all struggle at times.

“The film Amadeusreally explored that idea beautifully, as somebody very gifted being simultaneously flawed.” For instance, John Lennon; “All those amazing songs he wrote about love and unconditional love, and the power and freedom that’s connected to loving your neighbor well. And then you think of Lennon’s personal life, and the bitterness that he struggled with, and I realize that people like Townes and John Lennon aren’t necessarily writing a personal history of what is happening, they’re writing about what they are aspiring to. And I love that tension. I often write what I’m aspiring towards. That’s why anybody can hand something beautiful to the world. You don’t have to be all the way there, but if you can see it out in front – if you can tune into that vision or whatever – you can have something to say.”

One of the standout tracks on the new album, ‘All My Favorite People’ deals directly with the dichotomy. “I came out with it as I surveyed my own life and my whole family. Karin and I looked at each other one day, and one of us said ‘All my favorite people are broken.’ And we explored that. I worked on the song over the course of a couple of years, figuring out what’s trying to be revealed.

“I was working on a line: ‘I see each wound you have received as a burdensome gift;’ and whenever we make a pronouncement like that, a good editor will step in. We edit each other, and often find ourselves reframing our songs in terms of questions, and Karin made a slight tweak. She changed it to: “Is each wound you’ve received just a burdensome gift?” It’s just a subtle shift of what’s happening in terms of the conversation, where I’m putting the question out there: Iwonder about this, Ithink I’m learning something about this – what are you learning? And those kinds of conversations are what we are really interested in.”

In an industry where acts come and go with regularity, remaining a viable entity for two decades is a remarkable achievement. How has Over The Rhine endured? “Fortunately, we have people that have stuck with us from the very beginning. And along with that we have people that continue to discover the band every time we release a record. People are still finding out about us.

“Our audience is pretty diverse. If we play a concert that’s restricted to 21 and over, we will usually get emails from kids in college saying “are you sure there’s no way we can get in?” That’s maybe the most encouraging part of the equation; that young people are still getting excited about the music.”

With radio no longer able to break acts, and brick and mortar stores carrying fewer CDs, traditional methods of reaching an audience no longer apply. “A lot of it is word of mouth, and a lot of it revolves around our vision of connecting directly with our listeners. We were one of the first bands in America to have our own website. It was a kid at MIT that set it up for us and we barely knew what it was. It had a URL of about 46 characters; we kept it on a server at MIT’s campus.”

From the start, they took a hands-on approach. “We were stapling together hand-written newsletters and mailing them out, and really trying to not let other people do that work for us. Even if we were signed to a major label, we wanted to maintain a direct connection.”

From the start, they took a hands-on approach. “We were stapling together hand-written newsletters and mailing them out, and really trying to not let other people do that work for us. Even if we were signed to a major label, we wanted to maintain a direct connection.”

That connection is largely responsible for The Long Surrender. “When we realized we were going to be making this record with Joe, we looked at different options for funding, and decided to go directly to our fans; to tell them about this opportunity and invite them to step in and fund this record and make it with us.

“That could involve preordering a CD at $15, which meant you would get the CD couple of months before it came out in stores, your name listed on the band’s website, and bonus tracks, all the way up to $10,000; where we’ll come do a private concert, put you on our guest list for a year, and give you a whole bunch of other treats.”

They had takers at every level. “We had a little over 2,000 people participate. One couple in Austin, Texas pitched in ten grand. We’re going to go down there in the spring and play a show in their barn for them and their friends. We just had one taker at that level, but the important thing is we got the entire project paid for, and we got to treat it as a barn raising, or a community effort.

“I think people really appreciated being part of process and seeing it come together. We sent the demos out to a lot of the donors, so they got to hear sort of the early versions of these songs, hear some of the songs that didn’t make the final cut, and be part of the whole process.”

The new business model is a radical departure from the past. “It’s extremely preferable to having a record label loan you the money, and then take 80% of the proceeds forever. Nowadays, there is no middleman; it’s really just us and you. It’s a fairly new idea, but other songwriters have done it, and it made perfect sense.’

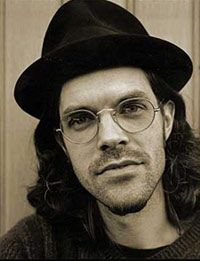

The choice of Joe Henry as producer was inspired. In addition to his own catalogue of stellar solo releases, over the last decade he’s become a producer of note, with Solomon Burke, Bettye LaVette, Aimee Mann, Mose Allison and others benefitting from his skills behind the board. The paring with Over The Rhine is a natural; Henry is willing to mix things up, creating a unique blend informed by what has come before while offering fresh takes on long-established artists.

“Like a lot of people, we had been noticing the records that he was producing, and we were getting really interested in his gifts as a producer. I loved the Solomon Burke records and the stuff he had done with Elvis Costello and Allan Toussaint, but I couldn’t quite figure out what that would mean for Karin and I. And we loved that idea of not being able to imagine the record in advance. It was a bit of an unknown, and that’s very exciting – when you trust a person – it’s very exciting to open yourself up like that.”

“Joe is a great writer, and there was an intuitive connection on that level. But there’s fearlessness; an element of danger about what he is doing. He’s not necessarily approaching it as ‘how do we make this an easy experience for the listener?’ It’s more like: ‘let’s blow the seams out of the songs.’

“We sent him all the demos and he had great feedback. He had this list; a couple of nudges here and there in a certain direction, but he put most of his work into carefully assembling the players for the record. Most of the hard work went to figuring out who needed to be in the room. He got an amazing group of players that really wanted to tune into what Karin was doing. And then he steps back and very gently orchestrates the proceedings. We were able to do what it is that we do; sit at the piano and play these songs with complete commitment and abandon. It was like leaning back into a great comfortable chair. We were effortlessly swept away, like we had been put on a train after dark; everything just started to move out of the room. It’s hard to explain, but it was embarrassingly easy to make the record,” he laughs. “We didn’t labor. We started on a Monday afternoon and wrapped up the following Friday afternoon.

“Joe kept track, and at least six or seven of the tracks on the record were first takes.” Like old school sessions, everything was live off the floor. “Everybody was playing together. If we did do a second take, Karin sang the entire song again every time.”

In every case, the vocals are entire performances, from start to finish. “Those are complete, intact performances. No overdubbing. Karin sang all that stuff live.”

They co-wrote two songs with Henry. “When we showed up at the sessions, Karin had one song that we felt really belonged on the record musically, but she just had one word, and the word was ‘soon,’ and I think it was Thursday, we were almost done, she asked Joe if he’d want to take the shot at writing the words.

“So before breakfast she had that lyric in her inbox. She made a few tweaks and we went in and sang the song. And it’s got some of my favorite lyrics on the record.”

While the musical component is obvious, Henry’s personal life made an impression as well. “When we were exploring the idea of making a record together, Joe mentioned that his parents were going to be attending one of our shows. It was a coincidence; they had heard us on one of the NPR stations and we were playing in Shelby, North Carolina where they live. Joe wrote a short tribute to his parents, because he knew that I would be meeting them. And I remember responding and saying what a rare pleasure, to read such well articulated love. I just couldn’t believe that Joe would take time to send me this letter in appreciation of his parents, in advance of us having the opportunity to meet them.”

That initial impression was cemented after Detweiler and Bergquist traveled to Henry’s home in California for the recording. “It’s a special family, where encouragement, support, and love are the order of the day. I’m sure they’ve had their difficulties along the road, like anyone has. But it’s been a gift to see a family care for each other so well. That was the atmosphere we were in while we were making the record at Joe’s house; you can’t help but encounter the whole package”

“And then, seeing the attention Joe pays to the details of his life; he can make an incredibly good cup of espresso,” he laughs. “Whether it’s that, or it’s the music that he chooses to listen to at dinner time – he mostly listens to older traditional jazz records and sometimes he’ll play songwriters, but I found it to be incredibly inspiring. It was kind of the week of a lifetime. It’s been an amazing new friendship. We really enjoyed that process and look forward to more.”

When I spoke with Karin back in 2006, the couple was in the process of healing after a particularly rough patch in their marriage. They’re still together, and thankful.

The album that precipitated the break (Ohio) was one of their strongest. Artistically, they were on a high. “That’s the thing; we got so caught up in touring and everything that was happening around that particular record that we just kind of ran out of gas when it came to loving each other apart from all of that.”

Rather than continue, they called off an important tour. “We shut it down for a little while, went home and kind of recalibrated. When the momentum begins to build for a relationship to blow apart, it can be a real challenge to find that fresh beginning. And I think we were part of the fairly small minority that were able to turn it back around and make a fresh start.”

The new album’s title, The Long Surrender, speaks to the realization that life can be hard, and issues sometimes ongoing. “I think it’s universal. And when it comes to Karin and I, the biggest take away from that chapter was the fact that we had two things that we were nurturing simultaneously; a marriage and a songwriting partnership. And they both require a certain amount of creativity and care and commitment. We made the mistake when we were younger of thinking that if the songwriting is humming along, then we could put the marriage on hold indefinitely if we were on the road or whatever. Learning to balance both – taking care of both – on an ongoing basis is something that we continue to experiment with. But I’m extremely grateful that we’ve made it work.

The new album’s title, The Long Surrender, speaks to the realization that life can be hard, and issues sometimes ongoing. “I think it’s universal. And when it comes to Karin and I, the biggest take away from that chapter was the fact that we had two things that we were nurturing simultaneously; a marriage and a songwriting partnership. And they both require a certain amount of creativity and care and commitment. We made the mistake when we were younger of thinking that if the songwriting is humming along, then we could put the marriage on hold indefinitely if we were on the road or whatever. Learning to balance both – taking care of both – on an ongoing basis is something that we continue to experiment with. But I’m extremely grateful that we’ve made it work.

“Karin and I always had really good chemistry musically, and that was the first sort of connecting – music was what connected us initially, and then we realized that we were in love. And so I don’t know if they’re completely intertwined at this point, or if one could exist apart from the other. But let’s hope that we never have to figure all that out.

It’s clear that Over The Rhine’s audience is a vital part of the equation. “We’ve described that as people inviting our music to be part of the big moments of their lives,” Detweiler explains. “When that begins to happen, a deep relationship begins to form.”

He recalls a defining moment early on in their career. “We were getting a lot of letters, and I remember one day spreading eight or nine different letters out on a table, and it spanned a lot of human experience, beginning with: “I just wanted to let you know I fell in love and met my fiancée in college and this particular record was sort of our personal soundtrack for all of that.” That would be one letter. Then the next letter would be: “We were married last month, and we danced our first dance to this particular song on this particular record.” The next letter would be: “We took your records to the hospital; we were giving birth and they played them continuously, so you were there in spirit.” And I remember this letter from an old Irishman in particular, he had gone into the hospital to have surgery for cancer, and he took one of our records, and a couple of songs in particular that almost functioned as guardian angels for him, as he listened to this music in the hospital. And then the last letter was talking about burying a loved one, and a particular song the family had embraced as a mile marker for that season of loss.

“We were looking at each other, and obviously some writers and artists have various concerns when it comes to making a living – achieving a certain amount of recognition so that you don’t have to worry about paying last month’s bills – but on the other hand, we realized: what greater reward could there possibly be than to have the music finding its way into these big moments? Really: what more can we ask for? That’s continued to happen, and as long as we feel like we’re doing good work that people are continuing to embrace on that deep level, it’s enough to keep us going.”

© John Cody 2011