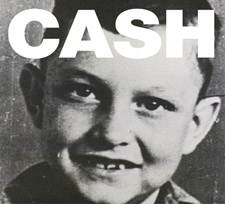

It’s been well over a decade since the record buying public began to reassess older performers. That change in perception began with Johnny Cash.

It’s been well over a decade since the record buying public began to reassess older performers. That change in perception began with Johnny Cash.

By the time he hit his sixties, Cash was considered a spent force. The country music industry had cast its one-time golden boy adrift, and – dropped by two successive record labels and without a contract for the first time in his career – his prospects were decidedly bleak.

His profile was raised in 1993, when U2 invited him to sing ‘The Wanderer,’ which closed their Zooropa CD , but it was the following year that everything changed.

That was when Rick Rubin – famous for producing rap and metal acts like Slayer, Danzig and the Beastie Boys – took him into the studio for the first in an ongoing series of American albums.

Refusing to follow trends, Rubin’s formula was deceptively simple – initially just Johnny and his guitar, later efforts featured sparse, understated accompaniment – and would eventually return him to the top of the charts 40 years after his only other #1 album.

The final installment in the series, American VI: Ain’t No Grave was released earlier this year, in conjunction with what would have been Cash’s 78th birthday.

The final installment in the series, American VI: Ain’t No Grave was released earlier this year, in conjunction with what would have been Cash’s 78th birthday.

That the album exists at all is testament to music’s power to soothe and heal. It was recorded under almost unbearable circumstance; his wife June Carter Cash had died during the sessions, and Johnny’s own battle with Parkinson’s disease was taking a toll; he would be dead three months after the final sessions were completed.

Yet, it’s anything but morbid. The opening title track is a defiant declaration that death has not won. It’s an ongoing theme throughout the disc. Despite suffering pain and loss, there’s an almost celebratory feeling to many of these songs.

Cash’s final composition, ‘I Corinthians 15:55,’ quotes directly from scripture; “Oh death, where is thy sting?/Oh grave, where is thy victory?”

There’s no fear or trepidation. Alongside songs that deal head on with the heaviest of subjects are covers from a wide range of sources, including folk standards ‘Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream,’ and ‘Wonder Where I’m Bound,’ Kris Kristofferson’s ‘For The Good Times,’ and ‘A Satisfied Mind.’

The disc concludes with ‘Aloha Oe,’ a traditional Hawaiian song of farewell that ends with the prophetic lyric, ‘until we meet again.”

Ain’t No Grave runs barely over a half hour, yet feels complete.

Merle Haggard and Willie Nelson have experienced similar creative renaissances to Cash; despite being abandoned by Nashville, in the last decade, each has released albums that rival their best work.

While undisputedly country-based, both work from a wide, varied musical spectrum, with blues, folk, and even jazz finding its way into their repertoires. Like country philosophers, they’re deceptively simple in their delivery, with a laidback, easygoing sensibility.

More than any singer alive today, Haggard reflects the values of the working man. Plainspoken and to the point, there’s an uncommon wisdom that runs through his best songs.

Cash may have sung about being a wanted man, but Merle actually did the hard time. While incarcerated at San Quentin, he witnessed Cash perform for inmates three times. Those shows changed his life; he came to the realization that he could do this, too.

Cash may have sung about being a wanted man, but Merle actually did the hard time. While incarcerated at San Quentin, he witnessed Cash perform for inmates three times. Those shows changed his life; he came to the realization that he could do this, too.

More than half a century on, his repertoire of classics have been covered by literally hundreds of acts, from Dean Martin to the Grateful Dead, Joan Baez and Lynyrd Skynyrd to – well – Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson.

A recent bout with lung cancer necessitated having part of a lung removed. Ever the trouper, two months later, he was back on the road.

At 73, he’s seen more than most, including watching both Elvis and Bob Wills perform, as he sings in ‘I’ve Seen It Go Away,’ so there’s not a lot that’s going to impress him. Through it all – the good times and the tears – comes the toughest lesson; “the sad part is, I’ve seen it go away.”

‘Pretty When It’s New’ looks at love from a similar perspective; “Old love’s even sweeter/that old saying’s really true/loves is always pretty when it’s new.”

‘Pretty When It’s New’ looks at love from a similar perspective; “Old love’s even sweeter/that old saying’s really true/loves is always pretty when it’s new.”

‘Live and Love Always’ features Merle on fiddle, doing his best Bob Wills, cheering on his wife as she takes over on lead vocal duties.

Haggard has released gospel albums in the past, including 1971’s Land of Many Churches, and 1981’s Songs for the Mama That Tried. Here, those songs are simply part of who he is, and sit naturally alongside the rest of the material, including the title track’s concise world view: “I believe Jesus is God / and a pig is just ham / I’m just seeker / I’m just a sinner / I am what I am.”

It’s hardly a boast. After all these years, there’s nothing left to prove. Instead, there’s an overarching sense of humility; no bold statements, just the unvarnished truth.

Despite being one of his generation’s finest writers, Willie Nelson’s latest; Country Music is – bar one track – comprised of cover material. That’s been a constant in his recording career; Nelson seems as happy showcasing other’s work as he is playing his own formidable body of compositions.

Despite being one of his generation’s finest writers, Willie Nelson’s latest; Country Music is – bar one track – comprised of cover material. That’s been a constant in his recording career; Nelson seems as happy showcasing other’s work as he is playing his own formidable body of compositions.

At 77, he’s as prolific as ever, with over 20 albums released in the last decade alone. This time out, with T Bone Burnett in the producer’s chair, he concentrates on country classics (‘Dark As A Dungeon,’ ‘A Satisfied Mind,’) as well as gospel-informed numbers like ‘I Am A Pilgrim,’ ‘Nobody’s Fault But Mine’, and ‘Satan Your Kingdom Music Come Down.’

The album’s title might sound confining, but Nelson’s version of country is far wider than the term can imply. A cover of Al Dexter’s 1942 hit ‘Pistol Packin’ Mama’ harkens back to the western swing sound as popularized by Bob Wills & His Texas Cowboys in the 1930s and 40s. That big-band-meets-country style was a crucial influence on Nelson and Haggard, both of whom have visited the genre repeatedly during their careers.

Haggard released A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player (Or My Salute to Bob Wills) in 1970, with many of the original Playboys alongside, and last year’s Willie And the Wheel coupled Nelson with Asleep at the Wheel, the foremost proponents of the western swing sound.

Nelson’s inherent swing, coupled with a decidedly laid-back approach, has garnered some significant fans from the jazz world; Miles Davis wrote and recorded ‘Willie Nelson,’ in his honor, and Country Music was preceded by Two Men With The Blues; a duet album with jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis.

Not bad for a senior citizen.

© John Cody 2010