Some of the finest music released in the 1960s came from a band called Love.

Although never a household name, for a brief three year period they were the toast of their hometown of Los Angeles.

By all accounts they should have been huge; but self-inflicted barriers – drugs, egos and a steadfast refusal to tour – insured were barely noticed outside of their home state.

The band broke up forty years ago; but their music has more than stood the test of time.

This year they received their first Grammy award. Alongside belated industry recognition, a feature-length documentary and a deluxe reissue of their crowning achievement offer compelling arguments for why Love mattered.

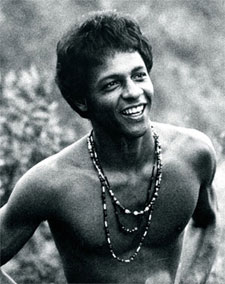

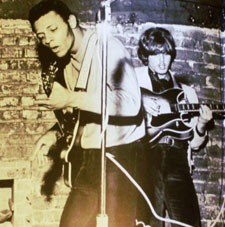

Fronted by Arthur Lee – an inspired, unpredictable mad genius – and right had man Bryan MacLean, their blend of rock, folk, jazz, psychedelia – even flamenco – was absolutely unique.

The band’s spring 1966 debut, ‘My Little Red Book,’ served notice they had pop smarts, but there was much more; their first album showed the influence of the Byrds, then far and away the biggest of all the L.A. groups. Twelve-string guitars are prevalent throughout, and MacLean – whose softer, romantic songs were a tonic to Lee’s more aggressive persona – had been a roadie for the band. He brought the song ‘Hey Joe’ with him; the Byrds hadn’t got around to recording it yet, and it was hastily planned as Love’s debut single. Both were beaten to the punch by the Leaves, who saw Love perform the song live and rush released their own version, scoring their only hit in the process.

The band’s spring 1966 debut, ‘My Little Red Book,’ served notice they had pop smarts, but there was much more; their first album showed the influence of the Byrds, then far and away the biggest of all the L.A. groups. Twelve-string guitars are prevalent throughout, and MacLean – whose softer, romantic songs were a tonic to Lee’s more aggressive persona – had been a roadie for the band. He brought the song ‘Hey Joe’ with him; the Byrds hadn’t got around to recording it yet, and it was hastily planned as Love’s debut single. Both were beaten to the punch by the Leaves, who saw Love perform the song live and rush released their own version, scoring their only hit in the process.

Like the Byrds, Love’s track selection was delightfully eclectic; ‘Mushroom Clouds’ was a gentle folk ballad worthy of Peter, Paul and Mary, while ‘Emotions’ harkens back to a long-gone trend; surf music. In this case, the roots were genuine; bassist Ken Forssi had been with a latter-day version of the Surfaris, whose ‘Surfer Joe’ and ‘Wipe Out,’ are classics of the genre.

The cautionary tale ‘Signed D.C.’ was based on real events; original drummer Don Conka was fired as a result of ongoing heroin use. To varying degrees, every member of the band would later struggle with drug-related issues.

The cautionary tale ‘Signed D.C.’ was based on real events; original drummer Don Conka was fired as a result of ongoing heroin use. To varying degrees, every member of the band would later struggle with drug-related issues.

Album number two, Da Capo starts out even stronger than the debut, moving beyond their influences and exploring new textures with a half dozen first-rate tracks, including ‘Stephanie Knows Who,’ ‘¡Que Vida!,’ MacLean’s ‘Orange Skies,’ and their only top 40 hit; ‘Seven and Seven Is,’ a gnarly burst of punk energy that’s gone on to become a garage band staple, covered by everyone from Alice Cooper to Billy Bragg.

Any notion this was going to be a classic work was diminished considerably by side two, which is taken up in it’s entirety by ‘Revelation,’ a self-indulgent blues shuffle that’s likely the weakest song in the group’s catalogue.

Recording sessions were often fraught with tension. Lee was a stern taskmaster, and the fact he was capable of playing all the instruments himself only made matters worse. He had no qualms about berating the others, leading one member to grumble that a better name for the band might have been ‘Hate.’

Recording sessions were often fraught with tension. Lee was a stern taskmaster, and the fact he was capable of playing all the instruments himself only made matters worse. He had no qualms about berating the others, leading one member to grumble that a better name for the band might have been ‘Hate.’

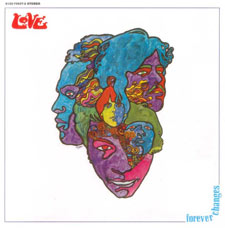

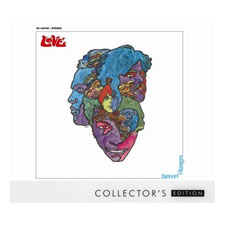

Everything came together on the third album. Released in November, 1967, Forever Changes regularly places in classic album surveys; many consider it to be the single greatest LP ever made.

Everything came together on the third album. Released in November, 1967, Forever Changes regularly places in classic album surveys; many consider it to be the single greatest LP ever made.

Things hardly looked promising at the outset. With the rest of the band incapacitated by heroin, Lee – who was ingesting LSD on a daily basis – sacked the entire lot, bringing in session musicians for two tracks. It proved an effective wakeup call; from then on, everyone was back and focused.

There’s more acoustic than electric guitar, and for the first time, strings and horns were used throughout, in every case enhancing the performance.

The album opens with what is arguably MacLean’s greatest composition; ‘Alone Again Or.’ The song – which has been covered by a wide range of artists including Calexico, Sarah Brightman, The Damned, Matthew Sweet, and UFO – is a heartbreaking tale of longing and loneliness, replete with unexpected key shifts, flamenco guitar break and an inspired trumpet solo.

MacLean’s other track would prove portentous. In ‘Old Man’ he sings of receiving a “small brown leather book” from a wise man who had seen the light. Afterwards, “things are not so strange, I can see more clearly.” Three years later, his world view would be radically altered, when he became a Christian.

MacLean’s other track would prove portentous. In ‘Old Man’ he sings of receiving a “small brown leather book” from a wise man who had seen the light. Afterwards, “things are not so strange, I can see more clearly.” Three years later, his world view would be radically altered, when he became a Christian.

Lee’s writing is far darker and contemplative; in addition to the Vietnam War and the civil rights struggle – both in full force at the time – premonitions of his own death informed his writing. Others were singing of peace and love; but Love conveyed the sound of the Hippie dream dying.

Lee’s writing is far darker and contemplative; in addition to the Vietnam War and the civil rights struggle – both in full force at the time – premonitions of his own death informed his writing. Others were singing of peace and love; but Love conveyed the sound of the Hippie dream dying.

‘Bummer In the Summer’ glimpsed the not-too-distant future: Charles Manson was just around the corner. Tracks like ‘A House Is Not A Motel’ and ‘Maybe the People Would Be The Times Or Between Clark And Hilldale’ brilliantly captured the confusing, transitional times.

The album should have been the band’s breakthrough. Instead, it proved to be their biggest flop to date, peaking at a meager #154 during it’s short run.

A follow-up single was recorded in January ‘68, but failed to chart at all. Work on a fourth album – provisionally titled The Garden of Gethsemane –was abandoned, and the band imploded a few months later.

The story should have ended there. Instead, Forever Changes took on a life of its own.

Reassessment began soon after it was released. 1970’s anthology Love Revisited quotes a New York Times critic from 1968; “I think we missed one…I think the new Love album may be one of the best rock albums of the year…but it’s almost a year old!”

Forty years on, it’s considered one of the seminal records of the era and essential to any serious collection of classic rock releases.

In addition to the album’s induction into the prestigious Grammy Hall of Fame this year, Rhino’s new double disc set Forever Changes: Collector’s Edition does things up right with extensive notes, unreleased and rare tracks, plus an alternate mix of the entire album.

In addition to the album’s induction into the prestigious Grammy Hall of Fame this year, Rhino’s new double disc set Forever Changes: Collector’s Edition does things up right with extensive notes, unreleased and rare tracks, plus an alternate mix of the entire album.

When the original band broke up, Lee continued to record with a variety of replacement musicians under the Love moniker. Invariably, subsequent efforts were disappointing when measured against what had come before.

Eccentric at the best of times, his behavior became increasingly erratic over the years. In 1996 he was sentenced to a 12 year prison term after firing a pistol into the air. On appeal, the conviction was overturned, and he was released in December 2001.

Making up for lost time, he began to tour extensively, performing Forever Changes for the very first time.

The concerts were an unqualified success, with ecstatic audience reactions, especially in Britain, where the band was always more popular than in the U.S.

Parliament proclaimed Forever Changes ‘The Greatest Album Of All Time.’ The Mayor of London – quoted on a DVD of Lee’s 2003 performance at the Royal Festival Hall – was equally effusive: “For my generation it was a landmark, an amazing piece of music I have been listening to ever since.”

The victory was sweet, but short-lived; Lee was suffering from acute myeloid leukemia, and passed away in August 2006.

His death adds poignancy to an already heartbreaking tale. Bryan MacLean and Ken Forssi both died in 1998, and with Lee gone, only guitarist Johnny Echols and drummer Michael Stuart remain from the original album sessions.

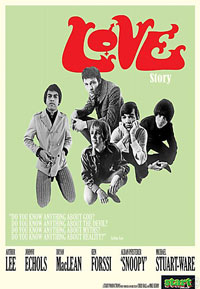

The recent documentary, Love Story, includes interviews with all five – MacLean and Forssi through archival footage – allowing the band’s turbulent history to unfold, contradictions and all.

The recent documentary, Love Story, includes interviews with all five – MacLean and Forssi through archival footage – allowing the band’s turbulent history to unfold, contradictions and all.

Echols puts their lack of success down to racism – he and Lee were both black – but that’s highly unlikely; multi-racial bands like Sly & the Family Stone and the Chambers Brothers were both reaching the top 10 charts at the time. Lee’s refusal to play outside of L.A. was enough to kill their chances alone.

Others intimately involved during the group’s heyday, including Elektra Records head Jac Holzman, producer/engineer Bruce Botnick and Forever Changes orchestrator David Angel, are on hand to offer their perspectives. Angel is blunt in his assessment; “I never heard any other group reach that level of art. I mean, The Beatles were a wonderful combination and they had the right stuff…but as far as a group that just created a kind of abstract rock art, I never heard anything like this group and that album.”

As the head of Elektra Records, Holzman had already experienced significant success in the folk market, with acts like Judy Collins and Phil Ochs, but Love – his first rock band signing – offered a doorway to a whole new audience. He recounts hearing ‘My Little Red Book’ on the radio for the first time – the first Elektra single to make the pop charts – whilst driving his car, and pulling over in tears.

The Doors – who recorded for Elektra after Lee insisted Holzman sign them – wanted to emulate Love, according to the band’s drummer, John Densmore. Jim Morrison incorporated much of Lee’s outsider persona, but at the same time, was willing to play by industry rules, touring incessantly, for instance. While Morrison explored and exploited the dark side, for all his eccentricities, Lee had a bigger heart; there was a sense of melancholy pervading his best songs, a longing to connect regardless of circumstance.

The film opens with a typically self-aggrandizing statement from Lee; “I don’t have to swear. I don’t have to say anything but the truth. There is God, and God is. I heard his voice. He spoke; he spoke and he said ‘Love on earth must be.’”

Later, he claims that just as Jesus said; ‘My words will never pass,’ so too, Arthur’s songs will never pass.

Occasionally, those songs addressed spiritual matters directly, espousing a theology that ranged from orthodox to peculiar.

He could appear selfless, as in the self-explanatory ‘I’ll Pray For You,’ whereas, from a theological and lyrical viewpoint, ‘The Everlasting First’ was downright quirky; ‘Ever since the first time I laid eyes upon you / You don’t know how hard it is to let you go / Even in the first when we were starting / I told you man was here to love but he had to go / So you killed Jesus, you killed Abraham too / you killed Martin, what you here to do?”

He could appear selfless, as in the self-explanatory ‘I’ll Pray For You,’ whereas, from a theological and lyrical viewpoint, ‘The Everlasting First’ was downright quirky; ‘Ever since the first time I laid eyes upon you / You don’t know how hard it is to let you go / Even in the first when we were starting / I told you man was here to love but he had to go / So you killed Jesus, you killed Abraham too / you killed Martin, what you here to do?”

‘Stand Out’ seemed to be written from a deity’s perspective; “You’re supposed to love me and if you don’t know why / Well I’m you ticket to get to heaven with / And that ain’t no lie. / I see a man lying on his deathbed all filled up with hate / You better put some love in his life / somebody said the hour it’s getting late.”

In typically rambling fashion, he discusses the end of the original band; “You have to forgive – I do believe – in order to be forgiven. Because people make mistakes, and people have choices to make, and when you’re at the crossroads, sometimes…you go on the wrong path…It’s like I went that way…and the band went that way.”

The competitive dynamic between Lee and McLean brought out the best in each of them. They would never again reach the artistic heights or popularity experienced during the band’s heyday. “Unfortunately,” Bryan laments; “neither Arthur nor I were as good apart as we were together.”

He claimed his goal – like Lee – was to write timeless music; songs that couldn’t be associated with any particular era, “that would still sound good, 30 years, 50 years later.” To that end, both succeeded admirably.

© John Cody 2008