In the early 1960s, Los Angeles was not exactly a bastion of rock ‘n’ roll. Home to Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Dean Martin and a host of other old school vocalists, the most contemporary sound – ironically – was coming from the folk revival, with acts like Bud & Travis, The Modern Folk Quartet and Joe & Eddie singing traditional songs to the college crowd.

In the early 1960s, Los Angeles was not exactly a bastion of rock ‘n’ roll. Home to Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Dean Martin and a host of other old school vocalists, the most contemporary sound – ironically – was coming from the folk revival, with acts like Bud & Travis, The Modern Folk Quartet and Joe & Eddie singing traditional songs to the college crowd.

Surfing groups and studio-concocted novelty songs like ‘Alley Oop’ were strictly for the teenagers, an audience rarely taken seriously by the powers that be. There were a few notable exceptions: Phil Spector – the first tycoon of teen – employed a bevy of session musicians to create his legendary Wall of Sound productions; and in 1962 a teenaged Brian Wilson mixed sophisticated Four Freshman-style vocals with Fender guitars to create an entirely new style that resonated right across the country.

After a dozen singles, ‘I Get Around,’ took Wilson’s group, the Beach Boys to the top of the charts in 1964, but by then, all bets were off.

Wilson – like seemingly every other musician in L. A. – was forever changed by the arrival of the Beatles in February 1964. The shake-up brought about a musical renaissance for the city, and a golden age for radio. For four glorious years, the Sunset Strip was the epicenter of all that was cool.

Clocking in at over five hours, Rhino Records’ comprehensive Where The Action Is! Los Angeles Nuggets 1965-1968 makes it abundantly clear that while the Beatles may have been the spark that lit the creative fires, there’s far more at work here than simple cause and effect; from the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield to Captain Beefheart and Tim Buckley, this was music that mattered.

Clocking in at over five hours, Rhino Records’ comprehensive Where The Action Is! Los Angeles Nuggets 1965-1968 makes it abundantly clear that while the Beatles may have been the spark that lit the creative fires, there’s far more at work here than simple cause and effect; from the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield to Captain Beefheart and Tim Buckley, this was music that mattered.

Henry Diltz of the Modern Folk Quartet recalls the evening the Beatles first performed on prime time television. “We were on the road. And instead of driving all night, we made sure we had a motel room early enough to watch Ed Sullivan. And we were mesmerized.

“I mean, we had sort of heard of the Beatles, and maybe had heard one song on the radio. You’d think, ‘wow, that’s really something.’ But to see them standing there, these four guys, playing their instruments, making that music… It was the joyfulness that got everybody; really infectious and joyful music.”

Even on a technical level, the quartet’s sound was a revelation; “On a recording, you can overdub all kinds of things; but they could just stand there and make that sound. And here we are plodding along,” Diltz laughs, “at least it seemed like that in comparison. So everyone said, ‘that’s what I want to do.’”

The rules had been irrevocably changed. “It was overnight. We said, ‘Well look, they’ve got a drummer, they’ve got an electric bass, electric guitars, so we’ve got to do that.’ And every folk group said that. And that’s when you got the Buffalo Springfields and the Byrds and those groups.”

For many, it came down to a choice; plugging in, or getting left behind. “It was just people saying, ‘Man I’m through with just plain ordinary generic folk music. I want to move on and do this thing that’s a step above.’ It seemed a lot more accessible.”

Ken Mansfield –who would later run the Beatles’ Apple Records in America – was managing a popular club called The Land of Oden when the Fab Four arrived.

“On the West Coast in those days it was the hungry i in San Francisco, the Troubadour in LA, and the Land of Oden in San Diego. Those were the three clubs where Bud & Travis and Joe & Eddie, the original guys out of the Association…these were the clubs they played. That first time the Beatles came on Ed Sullivan on a Sunday night, it was me and my waitresses, and maybe two people that didn’t know who the Beatles were in the audience. So the next time that they were going to be on, we put in our flyer [that at] 8:00, the entertainment would stop, and we put a TV up on the stage and the people would watch the Beatles, and then we went back to entertainment.”

Mansfield believes that the folk roots were solid – and adaptable enough – to withstand the upheaval. “The transition out of folk, especially if you look at the Byrds, it never went away; it just morphed into something else. Joni Mitchell, singers like Bob Lind and all these people; that didn’t go away real fast, they did a transition.”

Some groups never reached a consensus, and split right down the middle. Such was the case with the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers; “They used to play my club, and basically, half the group wanted to go electric, and half of them didn’t. So they did the split – the half that wanted to rock was the Byrds, and the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers stayed on their way. So it really did morph into this.”

Chris Hillman went from playing mandolin in the Squirrel Barkers to electric bass in the Byrds.

In his case, folk was as foreign as rock ‘n’ roll; “I was more of a bluegrass guy, and I cut my teeth playing down in the suburbs of Los Angles in hillbilly bars. I was playing mandolin with these guys that were like 30 years old. I was 18 and had a fake I.D. That was so completely different than what most of the people listened to, even [fellow Byrds] Roger [McGuinn] and David Crosby and Gene Clark. I was coming out of straight traditional roots music.”

Regardless of what had come before, every musician was impacted by the Beatles. “Oh God, everybody started plugging in,” Hillman laughs. “We started plugging in. We played the Troubadour Hoot night as the Byrds, and in front of all our friends – our folk music pals – we got hooted off the stage, and then we came roaring back, and we showed them, anyway.”

Modern Folk Quartet bassist Chip Douglas was in the audience for those early shows. ”The Byrds were just getting started. Crosby and McGuinn and Gene Clark would sit around in there on Monday nights. They’d do some Beatles songs, things like ‘I Should Have Known Better,’ and they were doing Beatles-sounding things. I had never heard ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ but I always heard them doing [sings]: ‘You showed me what you do/exactly what you do…’”

A few years later, Douglas, now producing the Turtles, remembered the tune. “I used to hear it at the Troubadour bar all the time. I just knew how it went from hearing it live so many times.” His 1968 production of McGuinn and Clark’s ‘You Showed Me’ netted the Turtles their fifth top 10 hit.

Part of the record’s appeal is Douglas’ sublime string arrangement, which was inspired by yet another L.A. single; “Around that time [Bobbie Gentry’s] ‘Ode to Billy Joe’ had been a hit. I loved those string parts on there, so I wrote some string parts for it. I was going for the ‘Ode to Bille Joe’ feel.”

The Turtles’ roots were far removed from the folk scene. As the Crossfires, they specialized in honkin’ surf instrumentals. By the time the British Invasion was in full swing, they had secured a house gig at the Revelaire Club in Redondo Beach, recalls singer Howard Kaylan. “Mark [Volman] and I had put down our saxophones, realized that we had a lot more future using our vocal talents, and were aping the hits of the day. So we were doing the Dave Clark Five, the Beatles…all the English Invasion bands.”

As the Byrds’ debut headed to the top of the charts, Kaylan, Volman and company were paying close attention. “We’d gone to see those guys, because we hung out on Sunset Boulevard, too. We saw them just as the record was coming out. Literally two weeks before, we went to see them at Ciro’s.”

They immediately added the song to their own repertoire. The very next week, a pair of record scouts showed up. “The two guys said; ‘We loved your set. We especially loved the way you did ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’”

The scouts offered to pay for a recording session – two originals as well as an electrified cover of a Dylan song – and insisted on a name change to something more contemporary. “I think we had ten days. In the ten days we had to rehearse the songs, change our name, and sign the contract.”

As the Turtles, their version of Dylan’s ‘It Ain’t Me Babe’ was on the charts and heading for the top ten before ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ had even finished it’s run.

The group’s transition was hardly unique. Surfers, like those in the folk scene, were faced with changing styles or appearing hopelessly out of step; as the Crossfires morphed into the Turtles, so the Fender IV begat the Sons of Adam. The curiously-named Fapardokly was in fact Merrell Fankhauser, late of the Impacts, and The Everpresent Fullness featured surf guitar legend Paul Johnson.

Then there were those with little or no previous experience.

After seeing the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, Jim Pons, a self-taught bass player who would go on to work with the Turtles, Frank Zappa, and Flo & Eddie, decided to put his own band together. Hand-picking each member – “guys that looked good” – to play frat parties while attending Cal State Northridge in the San Fernando Valley, their first-ever gig – as the Rockwells – was a double bill with Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band.

After finishing classes, they’d head out to catch the action along the Sunset Strip. When they Byrds left their regular slot at Ciro’s to tour behind ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ Pons got an audition for his group – by now calling themselves The Leaves – and secured the house gig.

Wholesome 50s rocker Pat Boone signed them to his production company. They never broke nationwide, but the band scored a number of regional successes. Most significantly, they were the first group to record ‘Hey Joe,’ which would go on to become a garage band staple covered by literally hundreds of acts, from Jimi Hendrix to Medeski, Martin and Wood.

“I don’t know why the Byrds hadn’t recorded it,” Pons notes. “It had been part of their stage act for months before we did it. Love was doing it on stage as well. I guess it must’ve fallen between the cracks of their scheduled studio times and release dates. And we recorded it three times before we had the hit!”

Encompassing everyone from Pat Boone to Jim Morrison, the scene in L.A. was the very definition of eclectic, with paths crossing constantly. In fact, according to Pons, the King of Clean very nearly aligned himself with the Lizard King.

Boone had asked him for a heads up on potential acts he could add to the roster. “I took him to the Climax Club on Santa Monica Boulevard one night to see the Doors. He was interested in expanding his management company and wanted to make an offer to Jim Morrison.” The meeting did not go well. “Morrison was drunk and disrespectful that night,” Pons recalls, “and nothing came of it.”

Boone was likely the only individual who would have identified himself as a Christian at the time.

Over the years, a number of others from the scene would come embrace the faith. Pons and Mansfield are both longtime believers; Mansfield has written three books dealing with his years in the business and journey to faith. In Beyond The Garage Sean Bonniwell, leader of the Music Machine, documents his path from astrology to born again Christianity.

Paul Johnson of the Everpresent Fullness and Barry McGuire went on to lengthy careers in the Christian music scene. Buffalo Springfield’s Richie Furay and Thee Midnighter’s Little Willie G are both pastors, while Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman from the Byrds, Love’s Bryan MacLean, and four members of the Turtles would all identify themselves as believers in later decades.

Love Is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965-1970 was Rhino’s first box in the Nuggets series dedicated to a specific region, and easily one of the reissues of 2007. Where The Action Is! maintains the level of quality, and is arguably an even more enjoyable listening experience.

Love Is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965-1970 was Rhino’s first box in the Nuggets series dedicated to a specific region, and easily one of the reissues of 2007. Where The Action Is! maintains the level of quality, and is arguably an even more enjoyable listening experience.

San Francisco players tended to treat their L.A. counterparts with disdain, labeling much of music ‘plastic,’ and claiming the city’s bands were contrived and designed to sell product. While the Monkees certainly fell into the category – they were created as a TV show, after all – there’s no question that even in their case, the music stands on it’s own merits; 1967’s ‘Daily Nightly’ – which features the very first Moog synthesizer on a pop record – sounds positively futuristic. In fact, as good as it is, much of the music produced in San Francisco during the same era comes across far more dated than the material included here.

The earliest track – a 1964 Byrds demo – captures the former folkies doing their best to emulate the Fab Four. By the time they released their debut single – a fully-realized, electric treatment of Bob Dylan’s ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ – the Byrds were leading the way, and even the Beatles were paying attention.

There were obvious advantages to being based in the film capitol of the world. ABC TV’s daily after-school program Where The Action Is, Shindig!, Hollywood A Go Go, Shebang! and more short-lived efforts like Malibu U broadcast local acts right across the continent.

A guide to local nightclubs underscores their importance in cultivating the scene. In June ’65, the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors authorized the opening of clubs catering specifically to the under–21 crowd. Age limits were lowered to 15, with many venues refraining for selling alcohol entirely.

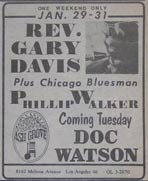

Booking policies were varied, but no club was more adventurous than the Ash Grove, which had opened back in 1958. “Within a two mile radius in Hollywood was the Ash Grove, and up the street was the Troubadour,” Chris Hillman remembers, “and it was worlds apart in the folk music period, prior to the Beatles. So at the Troubadour, you would hear the Modern Folk Quartet or a Kingston Trio-type band, down at the Ash Grove you’d hear – and I did see – the Stanley Brothers, Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs, Mance Lipscomb and Lightning Hopkins.”

For the audience, it was a crash course in roots music. Many would go on to notable careers themselves. Hillman met Clarence White at the club while both were still in high school. “It would be Ry Cooder, David Lindley, Herb Peterson… people that were more roots-orientated.”

The Ash Grove’s liberal booking policy impacted players far and wide. The Byrds’ ‘Eight Miles High’ – universally hailed as the first-ever psychedelic single – was influenced in equal parts by Ravi Shankar and John Coltrane, both of whom appeared at the club shortly before the song was recorded.

Due to heavy-handed licensing restrictions, only a handful of clubs were still catering to teens by the fall of ’66. Police had begun enforcing a 10 PM curfew for anyone under the age of 18, and in November, a crowd assembled outside of Pandora’s Box, one of the few clubs still allowing younger audiences. While tame by today’s standards, the incident was played up in the press as the ‘Riot on Sunset Strip.’

The following week, the L.A. City Council voted to review all remaining dance permits. After more than 1,000 teens protested, 400 members of the police and sheriff’s department showed up, arresting 43 kids. All youth dance permits were subsequently abolished, and anyone under 21 was forbidden from dancing.

Once the clubs were gone, the County Public Welfare Commission allowed venues that had lost their dance permits to feature topless entertainment and nudity. Somehow, hard liquor and nudity was deemed less offensive than non-alcoholic venues catering to teens.

A benefit for victims of the riots was held in February ’67, with The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and the Doors performing. Four months later, the organizers took on a far more significant endeavor by staging the Monterey Pop Festival. While the festival took place well outside L.A., the genesis and preparation all took place in the city. From the Association opening proceedings to the Mamas & Papas closing, L.A. bands were heard throughout the weekend.

The festival’s mandate to expose the best of the new music from around the world was a resounding success, with Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, Big Brother & the Holding Company (with Janis Joplin)and the Who – all gaining significant exposure.

Monterey has long been considered the ultimate gathering of the tribes. Hillman, who appeared with the Byrds, concurs: “The Monterey Pop Festival was the best rock festival. I don’t want to hear about Woodstock or the Isle Of Wight. Monterey was the best one. That’s when the companies realized ‘There is money to be made here.’”

Up until that point, the music industry was in the dark about just how popular the new music actually was. When the labels first got on board, they were happy to support the musicians, and simply make sure the records got to the stores. “It was really a little cottage industry, and it was run by music people. All these guys, from Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler at Atlantic to Mo Ostin at Warners, all these guys were music-oriented guys, and if you got signed – if you were lucky enough to be signed on a label deal back then – they’d keep you around for four or five albums.”

It was also a time when drug experimentation was considered a positive, hopefully mind-expanding experience. Tracks like ‘Take A Giant Step,’ ‘Pulsating Dreams,’ and ‘Tripmaker’ come across with an almost evangelistic glee.

The Leaves’ ‘Dr. Stone,’ from spring ’65 is described as “a bluesy ode to their favorite chemist.” Despite the connotations – and the fact LSD was still legal in California at the time – Pons says it wasn’t about acid at all: “The doctor I had in mind did not dispense LSD, only uppers and downers for us to take on the road. Most of our drug experimentation was mild by today’s standards… pot… uppers and downers [pep pills and sleeping pills]. Cocaine began creeping into the picture in the early to mid ‘70s, but by then I was on my way out of the music business.”

On first glance, there are a few inclusions that might appear out of place; Rick Nelson, Jan & Dean, Lee Hazlewood and Del Shannon were all from an earlier era, but it’s a testament to the spirit of the times; older acts were attempting to reinvent themselves, often with spectacular results.

Moving on from singing about cars and surfing, Brian Wilson was exploring the studio with what he referred to as ‘pocket symphonies.’ ‘Good Vibrations’ and ‘Heroes and Villains’ (an outtake is included here) were a world away from his trusty 409.

Wilson’s ornate orchestration was an obvious influence on the Full Treatment, the Yellow Balloon, and especially Curt Boettcher, who shows up twice, on ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’ (credited to the Ballroom) and the even more obscure ‘Don’t Say No’ by The Oracle. As Sagittarius, former Wilson co-writer Gary Usher tackled the metaphysical with ‘The Truth Is Not Real.’

The set’s one ostensible throwback; ‘Back Seat ’38 Dodge’ by Opus 1, turns out to be nothing of the sort. Inspired by the notorious Ed Kienholz sculpture of the same name, the lyric ‘What goes on/I really want to know’ refers to a race that has little to do with cheater slicks or hemi power.

In stark contrast to the sophisticated studio-laden acts, The Standells, transplanted Texans the Bobby Fuller Four, the Music Machine and a myriad of other garage rockers kept things simple and direct. Thee Midnighters – described as ‘undisputed kings of Chicano rock’ – offer a gritty Tex-Mex punk, which would influence Los Lobos twenty years later.

There are excursions into areas never again explored, as on Randy Newman’s fuzz-guitar-laden version of ‘Last Night I Had a Dream,’ and Harry Nilsson’s sole foray into psychedelia, ‘Sister Marie.’

At times, the debt to other acts is transparent. The Doors – who show up with ‘Take It As It Comes’ from their debut LP – were an obvious influence on Pasternak Progress, whose ‘Flower Eyes’ sounds like an outtake from Strange Days, and the Merry Go Round’s ‘Listen, Listen’ sounds like a lost Beatles track sung by John Lennon.

Hearts And Flowers’ ‘Tin Angel (Will You Ever Come Down),’ is intriguing. The group – including future Eagle Bernie Leadon – were pioneers in bringing country music into the mix, yet this rare single comes across like the Moody Blues at their trippiest, or conversely, something the Jayhawks would attempt today.

Three previously unreleased tracks – Buffalo Springfield’s Stephen Stills and Richie Furay singing ‘Sit Down I Think I Love You,’ a Tim Buckley outtake, and Boyce & Hart’s demo for ‘Words,’ a 1967 hit for the Monkees – are genuine finds, and worthy additions to each artist’s catalogue.

Radio stations invariably supported local acts. The Top 40 format was birthed in the city during the period, and while chart placement hardly counts for inclusion – many tracks never made it to the bottom of the top 200, and a sizable percentage have been unavailable since their original 45 release – it’s telling just how much of an impact the scene had nationwide.

After producing exactly one Billboard chart topper apiece for 1963 and 1964, L.A. acts increased their presence more than tenfold in 1965. The Byrds hit twice, with ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and ‘Turn, Turn, Turn,’ and along with the Beach Boys, Gary Lewis & the Playboys, Sonny & Cher and Barry McGuire collectively accumulated a total of 12 weeks at the top.

1966 proved even more impressive, with the Association, Beach Boys (their third successive year), Johnny Rivers, Nancy Sinatra, and the Mamas & Papas totaling 17 weeks.

1967 was the peak, with the Turtles, Bobbie Gentry, the Association, the Doors, Nancy Sinatra (two times – one a duet with her dad), and the Monkees (twice again – at this point they were the biggest selling act in the world) sharing between them an all-time high of 22 weeks in the top spot.

Due to a variety of factors, 1968 brought the end of Top 40 chart domination. Buffalo Springfield, Love, and the Mamas & Papas all called it a day, and the Association, Monkees and Beach Boys had begun to fall out of favor with the record buying public.

The newly popular FM radio format meant bands no longer had to adhere to a 3 or 4 minute maximum, and local acts like Steppenwolf and Crosby, Stills & Nash thrived in the new environment. Iron Butterfly’s In-A-Gadd-Da-Vida – with it’s side long title track – became the first LP to go platinum.

L.A. continued to produce great music, but there’s no denying that 1965-1968 was a truly golden era for the city, and music fans everywhere. Where The Action Is! offers 101 reasons why.

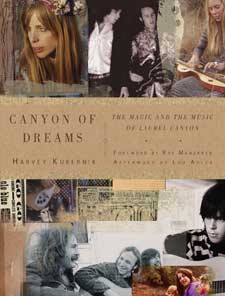

With it’s close proximity to the Sunset Strip, Laurel Canyon was, as Van Dyke Parks once put it; ‘the seat of the beat.’ There’s an ongoing fascination with the locale; Harvey Kubernik’s oral and visual history, Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon (Sterling) is the third – and best – book in as many years to tell the story.

With it’s close proximity to the Sunset Strip, Laurel Canyon was, as Van Dyke Parks once put it; ‘the seat of the beat.’ There’s an ongoing fascination with the locale; Harvey Kubernik’s oral and visual history, Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon (Sterling) is the third – and best – book in as many years to tell the story.

Kubernik traces the area’s history, going back to the 1930s when Singing Cowboys like Gene Autry and Tex Ritter rode the range, through the fifties, as the cool school of West Coast jazz players took to the hills, and on to more recent times, as acts like Guns & Roses took up residence.

The heart of the book lies solidly in the sixties and seventies, when the elite of the rock community were based in the Canyon.

The list is impressive: The Byrds, Canned Heat, Sonny & Cher, The Doors, The Turtles, Monkees, Buffalo Springfield, Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young; Eagles and Carole King are just the beginning of a veritable who’s who of Canyon dwellers.

Kubernik, a long-time resident and chronicler of all things L.A., has known many of the players for decades, and gets the stories others have missed. Former residents, including members of many of the aforementioned bands, reflect on what made the place and time so special.

Music was the glue that held everything together, and from the clubs, radio stations and record companies to band dynamics and who played with who, it’s all covered.

There’s a personal slant to many of the interviews, including Lou Adler and Michelle Phillips sharing stories from their experience on the Monterey Pop Festival’s planning committee, and the three surviving Doors discussing the ups and downs of their all-too-brief career.

Henry Diltz – who in addition to singing in the Modern Folk Quartet is arguably rock music’s greatest photographer – lived there during the glory years, and supplies numerous previously unseen photos. The book’s generous coffee table size allows Diltz’s shots to be seen at their best.

For anyone interested in the L.A. music scene, Canyon of Dreams is required reading.

© John Cody 2009