If you were to assemble a who’s who of jazz players from the last forty years, chances are good guitarist Larry Coryell has played or shared the stage with the majority of them. He’s certainly the only musician who can boast of playing with Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix, Dizzy Gillespie and Stéphane Grappelli.

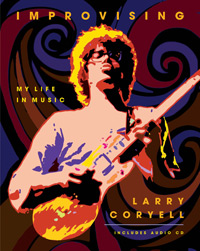

In Improvising: My Life in Music (Backbeat Books), Coryell documents forty years as a highly sought-after leader and sideman, with a discography that runs into the hundreds of albums. He also recounts his struggle and eventual victory over alcoholism and heroin, finds peace practicing Nichiren Buddhism, and survives a couple of nasty divorces.

In Improvising: My Life in Music (Backbeat Books), Coryell documents forty years as a highly sought-after leader and sideman, with a discography that runs into the hundreds of albums. He also recounts his struggle and eventual victory over alcoholism and heroin, finds peace practicing Nichiren Buddhism, and survives a couple of nasty divorces.

Speaking from his home in Florida, I found Larry to be sincere, forthright and most of all, passionate about his belief in the divine nature of all paths.

When he first began playing guitar in his teens, Coryell was equally enamored with rock ‘n’ roll and jazz; “I was very open-minded. The way I grew up – in a rural area of the state of Washington – just anything that was interesting music was appealing to me, and I didn’t compartmentalize at that time.” It was the sixties – perhaps the only era in which such widely divergent forms would be readily accepted.

He played standards in jazz combos and cover tunes with rock bands – even backing up stars like Roy Orbison and Bobby Vee – before dropping out of journalism school and moving to New York City in 1965.

The music scene was thriving. Jamming every chance he got in Greenwich Village nightclubs, Coryell became enamored with free jazz, an energized, radical sound that made everything before it – even bebop – sound antiquated.

The following year he recorded Out of Sight and Sound – the album was credited to the Free Spirits, but for all intent was a solo record – he composed, sang and played guitar throughout. Combining the rhythmic approach of rock with free jazz, titles like ‘Bad News Cat,’ ‘Cosmic Daddy Dancer,’ and ‘I’m Gonna Be Free’ – with Coryell on sitar – could only have originated during the era.

The following year he recorded Out of Sight and Sound – the album was credited to the Free Spirits, but for all intent was a solo record – he composed, sang and played guitar throughout. Combining the rhythmic approach of rock with free jazz, titles like ‘Bad News Cat,’ ‘Cosmic Daddy Dancer,’ and ‘I’m Gonna Be Free’ – with Coryell on sitar – could only have originated during the era.

Stuart Nicholson’s Jazz-Rock: A History lists Out of Sight along with Gary Burton’s 1967 release Duster – Coryell was the guitarist on that album as well – as “the first recordings that suggested an artistically and aesthetically satisfying synthesis of jazz and rock was possible.”

Almost overnight, he had become a force to be reckoned with. The New Yorker called him “the most inventive and original guitarist since Charlie Christian,” and the East Village Other labeled him “The most adventurous, daring and exciting guitarist playing rock or jazz…” His future looked assured as he worked alongside the very best in both worlds; jazz heavyweights, including Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, and Pharoah Sanders – and rock legends like Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix.

The sound he helped birth – “the pioneer” according to All Music Guide – achieved widespread recognition when Miles Davis released 1970’s Bitches Brew. It’s unarguably a brilliant, landmark album, but the fact it’s mistakenly credited as the first to incorporate both forms does a disservice to Coryell’s pioneering efforts.

The movement would explode commercially in the mid-seventies, with Weather Report, Return to Forever, Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters and the Mahavishnu Orchestra all drawing sizable audiences, including a significant contingent of rock fans. By then, Coryell was helming his own group; The Eleventh House.

Fusion was arguably the last substantial movement of note in jazz. For the most part, that willingness to try something knew – to take chances – is long gone. Nowadays, neo-traditionalism sells. Players attempt to emulate – or, as Larry puts it; “Plagiarize; albeit, plagiarize well” – the giants of yesteryear.

He’s not impressed with the new conservatism; “There should be more looking out. Younger people – the ones who are really serious about jazz – need to compartmentalize and focus on the music for at least a few years, because it’s almost a scientific art form, there’s so much involved in really getting the fundamentals right…but once you get that down, then an artist is free to break out into anything.

“Then you can branch out and be like Joe Zawinul; [do] what he did in the sixties, and start writing stuff that’s really soulful and funky, but still grounded in jazz.

“Or what Wayne Shorter did; very, very open, and very much embracing styles outside of the rather rigid format of bebop.”

Pianist Keith Jarrett shared that same enthusiasm for exploring new sounds, although in his case, the results were quite different from those of Zawinul and Shorter; “He learned all of that stuff in jazz, and then he ended up writing fantastic legitimate works for strings. He’s done great stuff – incredible piano concertos in his own style.”

Taking chances and ignoring previously established musical boundaries was expected. “[For] my generation;” he sums up, “it’s just simply like that.”

For a period in the sixties and seventies, jazz players were drawn to mystical explorations, and Larry jumped in with both feet. “It was the Age of Aquarius, my friend; we were embracing other life philosophies that we thought might be better than the ones that we had. Especially because musicians that we respected were doing things like that, we also were drawn to giving that a try.”

In 1969 he became a student of Sri Chinmoy, an Indian spiritual teacher popular at the time. The guru gave many of his followers new, spiritual names; guitarist John McLaughlin became Mahavishnu, and Carlos Santana – whom Coryell introduced to Chinmoy – became Devadip. McLaughlin and Santana became ardent disciples for a season (they both left in the eighties), but Larry’s appetite for sex and drugs kept him from fully committing; “I left or lost interest of something. At that point my most important goal was to drink beer and get high…”

In 1969 he became a student of Sri Chinmoy, an Indian spiritual teacher popular at the time. The guru gave many of his followers new, spiritual names; guitarist John McLaughlin became Mahavishnu, and Carlos Santana – whom Coryell introduced to Chinmoy – became Devadip. McLaughlin and Santana became ardent disciples for a season (they both left in the eighties), but Larry’s appetite for sex and drugs kept him from fully committing; “I left or lost interest of something. At that point my most important goal was to drink beer and get high…”

There were no hard feelings when he left, and they continued to see each another when occasion allowed up until Chinmoy’s death last year.

One of the more contentious groups he managed to avoid was the Church of Scientology. It’s most well-known practitioners in the jazz community were Chick Corea and Stanley Clarke, who together led Return To Forever, one of the most popular of the fusion groups.

“I never got into that. I saw what it did for Chick. It really helped Chick’s life a lot; [he] became a different person. But something told me that I just shouldn’t. I never was drawn to it. Initially because I was told by some people who shall remain nameless, that they really asked for a lot of money.”

Money is just one of the issues detractors have focused on. Stanley Clarke became one of the few celebrities to speak out publicly against the religion after he left. Cautious of appearing to take sides, Coryell chooses his words carefully; “I don’t even want to get into it; it really did work for Chick, and of course I love Stanley, and these guys are my life-long friends. And [Return To Forever guitarist] Al Di Meola as well. But Al was just a kid when the Scientologists were proselytizing him, and he was rather uncomfortable.”

Astrology is an area that has fascinated him for years. In Improvising he cites one Astrologer in particular who has managed to predict – either directly or by inference – many of the important events in his life.

Having sampled from a wide range of philosophies over the years, his overriding conviction is that all paths lead to the divine; “You know; there are many, many Masters out there; you just have to grab onto some life philosophy in your life, and get it and believe in it – almost no matter what it is – because it’s just a necessary thing to cope with the modern world.”

Despite his reputation as a player, for a variety of reasons, Coryell’s initial success was never capitalized on. His numerous solo albums – over seventy at last count – all had their moments of brilliance, but were rarely consistent stylistically. He had the respect of his peers and the press, but personal issues were another matter. He loved to party, and by the seventies, drinking had become a problem. When a therapist sent him to a twelve-step program, it didn’t take; he agreed to stop drinking, but continued getting high.

Life become an endless round of disasters; “I was a hurtin’ buckaroo. I mean, I had all kinds of opportunities; my career was rising and rising, and I kept shooting it down by my own hand.”

The slide continued until 1981, when the options had come down to a “decision between life and death.” He entered rehab, and this time, stayed straight. He hasn’t had a drink or drug since.

Many jazz players used heroin as a means of tapping into what made Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and John Coltrane – all junkies at various times – reach such musical heights. Larry was one of them; “Well, yeah. But I used that as an excuse.” For an addict, a very convenient excuse; “For me it was. I mean; I was very immature. I had talent, I could play. I could see that very early on. But I had not evolved. The rest of the areas of my personality were really kind of in the dark.”

Once he sobered up, he began to understand the impact drugs and alcohol can have on a family dynamic. His father was an alcoholic musician who had abandoned the family when Larry was still a child. Today, he believes he was predestined to live life as a musician with an addictive personality; “Absolutely; in my opinion – based on my experience – a lot of it is congenital.”

That concept – that his problems weren’t simply the result of personal weakness – came as a revelation; “Once you understand that it’s kind of like a disease – when you understand the treatment for taking drugs and drinking is simply not taking drugs and not drinking – then you’re able to approach it in a rational way, even though it’s not easy. One can deal with it rather than living with the shame and the stigma of negativity that is so often associated with all of that.”

The philosophy that finally stuck for Larry was Nichiren Buddhism. He had worked with a number of musicians who practiced the religion, a relatively new branch of Buddhism based on the teachings of Nichiren, a thirteenth century monk. A core doctrine is the practice of chanting.

“I was extremely impressed with the way Wayne Shorter and Buster Williams and Herbie Hancock had changed as a result of their starting to chant. I liked the way they had changed. They kept saying ‘You gotta do this; you gotta try it.’ One thing led to another, and I found myself in the middle of an empty field in France, chanting. Chanting just for the willingness to stop taking all mood-changing substances.”

The motivation to chant was intrinsically linked to his new-found sobriety. “When I walked out of rehab, I was determined that no matter what would happen in my life, I would no longer go back to that poisonous and destructive lifestyle. I felt good about getting actively involved in chanting and joining the organization.”

His passion is unmistakable, and he’s eager to explain just what sets Nichiren Buddhism apart from other branches of Buddhism.

“Nichiren Daisho¯nin lived in the 13th century, in Japan, and after he died he passed on his legacy to some priests, who were his disciples. During the course of the several hundred years that passed – up until the last century – it remained a viable school of Buddhism. But in the last century some Japanese educators got together and formed a value creation society based on the principles embodied in the Gohonzon, which were basically that Buddhism is life itself, and people – especially students – needed to be treated like people. And they started a whole pedagogy of education based on that.”

He didn’t expect an instant cure-all when he started; “I knew that chanting wasn’t like a magic lamp; sometimes it takes time to have your prayers answered.”

Today, his life is centered around the practice.

“We have a beautiful Gohonzon; [a scroll adherents are given] it’s enshrined in our home…what’s written on the scroll, is Nichiren Daisho¯nin’s enlightenment to the law of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo. [Pronounced Naam Nee-oh-hey Rengay-kyo].

“When we chant to the Gohonzon, we are taught that all the other Buddhists in all the directions of the Universe line up behind us and support us and chant with us. And you magnetize your life.

“You’re in a state of Buddha-hood when you chant to the Gohonzon. And you go back to the other states of life – the lower states – when you stop. But as you do it over a period of time, you raise [your consciousness] – you have a tendency to be more like a Bodhisattva [an individual dedicated to attaining enlightenment for himself and others], or at least someone who is interested in truly understanding the nature of things the way they are, and less of being in the animalistic state of life. Or a depressed state of life. Or angry; it works for everyone in all conditions.”

Time prior to his morning ceremony is rarely focused; “I’m always a little befuddled – a little negative and distracted. But when I chant, I think about what I want to accomplish that day, I also open up my life through the chanting; I stop thinking so much about myself, and I start thinking about other people.”

Part of his routine includes chanting for friends who have passed away. When saxophonist Steve Marcus – who recorded a number of early fusion works with Larry – learned he was dying in 2005, Larry convinced him they should chant together, even though Marcus had never tried before. “When you chant, that’s the highest, most compassionate act you can do to another person. Even though it was brief, I’m glad that we chanted together. Because I feel that where he is, he’s happy now. He’s in a state of non-substantiality. He had a great sense of humor, and when I’m really chanting a lot, I’ll recall one of his jokes, and I’ll break out laughing.”

Marcus received a traditional Jewish service when he died, which didn’t phase Larry in the least; “Oh, that was beautiful. That still was beautiful.”

Eric Fuchsman was another friend. As director of sales at Cort guitars, he worked closely with Larry, and when he was diagnosed with a brain tumor, Coryell sent him daimoku [the repeated chanting of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo] for hours on end. “I still feel him – feel his life is still important. I even wrote a song called ‘We Miss You, Eric,’ that I recorded. It’s going to be put out by the guitar company. Danny Gottlieb played drums on it.”

He believes they will all return to earth to continue working on their music, and chants “not just for their lives, but for the music…I chant in great appreciation for their contributions.” It’s a term he doesn’t take lightly. “Appreciation; in the Western word, it seems that it’s a lost art. It’s considered kind of corny and hokey.

“Billy Higgins, for example; nobody could ride their cymbal – no one could ride that ride cymbal like Billy Higgins. And Billy was a very beautiful human being, as well as an amazing drummer. But the quality of his humanness came out in his drumming. And whenever I think about him, I chant to appreciate what he has done. And I also chant for him to come back real soon. And do it again.”

He believes chanting is effective for people of all faiths. “You can come from any religion. I come from the Protestant religion. And now that I chant full time, I don’t need to go to the Protestant Church. But we don’t reject it; we embrace it. The Buddhist practice covers everything.”

He believes chanting is effective for people of all faiths. “You can come from any religion. I come from the Protestant religion. And now that I chant full time, I don’t need to go to the Protestant Church. But we don’t reject it; we embrace it. The Buddhist practice covers everything.”

For instance, prayer? “Absolutely; it’s praying. When I’ve had real problems in relationships, I chanted a lot. Sometimes we chant for hours. I’m doing it right now,” he laughs; “one’s karma is always right in front of you. It’s always there. And through this practice you can change your karma. Through this practice you can change negativity into positivity.”

He’s thankful for his life today, and claims he can never fully repay the Universe – or God; “It’s roughly the same thing” – for his gift; “I truly believe that.”

Not that it’s been smooth sailing ever since he got straight. A year after he began chanting, his first marriage fell apart. He married again, but that relationship ended a few years back as well, after, he says, he began to grow emotionally, “evolving toward another type of relationship.”

He married again last year; “My third one – third and last one.” Both divorces took a toll, but he’s philosophical. “As things go in life, all those minuses – all that negativity – if I hadn’t gone through that, I wouldn’t appreciate looking out my window here in Florida, and appreciating the sunset, and being grateful for my life, and my wife – my new wife.”

“Buddhism is very, very deep.” He sums up. “I’ve been doing it now 23 years. It’s extremely deep.”

While he’s been influenced by many of the players who came before him, there are a few who have had an especially profound impact. John Coltrane stands at the top. Coltrane influenced an entire generation, both in his playing, and when he forsook drugs to follow a rigorous spiritual path.

“I was very much inspired by A Love Supreme. When I first encountered Coltrane’s music, I didn’t think I would ever be able to understand it, much less play any of his stuff, but over the years, by being around it, and working and re-working and studying and re-studying, I’ve been able to receive Coltrane’s gift.”

He holds another master – typically, from a totally unrelated musical genre – in equally high esteem; “I’m the same way with [classical composer Igor] Stravinsky. I’m just now relearning The Rite of Spring [Coryell recorded an acoustic guitar treatment of the piece in eighties, as well as Petrouchka and the Firebird Suite] and getting all kinds of ideas. I’m totally on the same page as Coltrane, when he said ‘Stravinsky is my universal musician.’ I have to go with that myself.”

I mention Warren Zevon, who was briefly mentored by Stravinsky. Larry was unaware of the connection, and impressed; “Unbelievable. Unbelievable. And so he became an Excitable Boy [Title track of Zevon’s breakthrough 1978 album]…I loved him. You know, I never knew much about him, but I just saw a review of one of his books, [I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead a recent biography of the late singer]. He and I would have gotten along.”

I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead is a vivid account of Zevon’s struggles with alcoholism, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and drug addiction, but the story doesn’t end there – it’s as much about redemption – in the end he has years of sobriety under his belt, made amends and reunited with family and friends. “Yeah, but his life is [still] a tragedy. I’m sorry, that’s my opinion, you know.

“After practicing Buddhism for twenty three years, this is one thing I’m sure of; life is eternal, and we do come back. And the people who love Warren can pray for his return, and that he can receive the kind of benefits in the next existence where he’s able to deal with his alcoholism, and overcome it.”

For addicts, those benefits are relatively recent; “For me, the great thing about living in the 20th Century is that there were ways to get sober that I don’t believe were available in earlier centuries.” He’s referring to the twelve-step program first modeled by Alcoholics Anonymous in 1935.

Coryell credits chanting as a positive factor in staying straight, but feels there needs to be more when battling addiction issues; “Well, I believe in support groups, too.”

Respecting the long-held principal of never speaking for or representing A.A., he won’t go on the record as to whether he’s a member; “People who are in twelve-step programs – one of the rules is never break you anonymity. So you have to stay anonymous.” That said, he will offer his heartiest endorsement; “I certainly recommend it…and the gift of sobriety – to be drug-free and alcohol-free – it gives you a new lease on life. And we don’t always appreciate it. We’re human beings; we can get down into the world of anger, self-pity and resentment – it’s normal – but there are ways to use all of that and become a better person.”

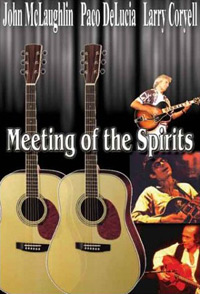

In 1979 he toured Europe as part of a trio of guitarists with John McLaughlin and Paco de Lucia. The tour was well received, but his drinking was out of control. “Alcoholics can’t stand success, and at that time I was doing everything I could to sabotage things with my drinking.”

When he wrote Improvising, he still couldn’t bring himself to watch the video from the tour. Recently, he found the courage; “It took me 30 years before I ever watched the concert [McLaughlin, DeLucia & Coryell: Meeting of the Spirits]. “I finally saw it; it was unbelievable.” He’s hopeful he can do it again, this time in a healthier state of mind; “I want us to play again, and I’m seeking out John and Paco as we speak. I feel like I was in one of the best groups ever. I just couldn’t handle it at the time. But those of us who are fortunate enough to survive this self-destructive thing, we do get a second chance, and in order to really take advantage of that second chance you have to work a little – a lot – harder. Because now I’m 64, I’ve got to take care of myself: doctor’s orders. I’ve got to loose weight, and eat different stuff; no sugar, no salt, that kind of thing.”

When he wrote Improvising, he still couldn’t bring himself to watch the video from the tour. Recently, he found the courage; “It took me 30 years before I ever watched the concert [McLaughlin, DeLucia & Coryell: Meeting of the Spirits]. “I finally saw it; it was unbelievable.” He’s hopeful he can do it again, this time in a healthier state of mind; “I want us to play again, and I’m seeking out John and Paco as we speak. I feel like I was in one of the best groups ever. I just couldn’t handle it at the time. But those of us who are fortunate enough to survive this self-destructive thing, we do get a second chance, and in order to really take advantage of that second chance you have to work a little – a lot – harder. Because now I’m 64, I’ve got to take care of myself: doctor’s orders. I’ve got to loose weight, and eat different stuff; no sugar, no salt, that kind of thing.”

Dieting issues aside, at least he’s no longer trying to destroy himself. “Yeah. That devilish function that gets inside everyone – the potential of the devilish function is in everyone’s life. It’s just how you deal with it.

“You know, the United States went through a revolution to become a country, and in a similar way, we have to go through our human revolution to become a Buddha. And a Buddha is not an extraordinary thing. It’s simply the effect that you receive from making the cause to become a Buddha by chanting. But look; I’m not Bishop Sheen. I’m no paragon of virtue; nothing like that. I have all kinds of faults and warts. I’m always fighting the negativity – you know – like, devils want to get inside my life and take over. But when my life condition is strong; I recognize them for what they are.”

© John Cody 2008