Imagine David Bowie fronting the Violent Femmes, or the Carter Family songbook as interpreted by Captain Beefheart.

For over a decade, Daniel Smith has been labeled a Christian eccentric. I recently mentioned Smith to a friend, who prides himself of being receptive to all manner of music, and his comment was, ‘you mean that weird guy?’ I spoke with Daniel last month, and found him to be anything but. He’s thoughtful, intelligent and – like his music – authentic and genuine. He’s well aware of the stereotypes and misconceptions.

“The terms that have been haunting me forever are ‘oddball’ and ‘Christian music.’ Two things that I’ve always said – I’m not trying to be weird, and I don’t make Christian music. I make music for everybody. I am a Christian – that’s different. Those are the tags that have been stuck on us – I believe – to neutralize what it is we’re doing.”

From Justin to Paris to the Pussycat Dolls – even Nelly Furtato – the most popular albums these days are completely concerned with booty-shaking and celebrating our more carnal instincts. In a climate where you can’t be too obvious, praising one’s Creator and singing about the joys of family is relegated to the ranks of outsider music.

Smith had just returned home after completing the group’s most extensive – and successful – tour to date, and I asked him about the make up of the audience. “It’s been a pretty split mix between [older] fans and a lot of people who just heard the new record and came to figure out what we’re doing. I’ve enjoyed having new fans there…it’s been this process [for] the first couple of songs, just kind of introducing what we do. More often than not there’s this transition halfway through the set – because we do this clapping along, and singing along, and trying to get the audience involved. The old fans, they were already on it from the first song, but a lot of folks aren’t sure if it’s cool or not.” He laughs. “Which it’s not. It’s not cool at all. But it’s fun.”

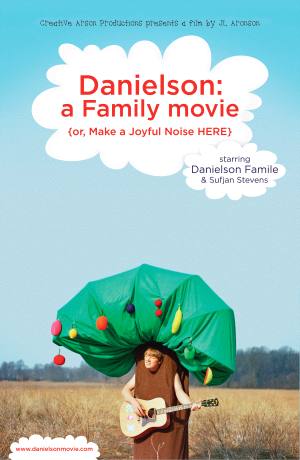

As the leader of Danielson, Danielson Famile, Brother Danielson and Danielsonship, Smith has produced a fascinating body of work over the past twelve years. With the release of Ships, the Danielson moniker has reached a whole new level of popularity. The album has already tripled the sales of previous efforts, and an upcoming documentary Danielson: A Family Movie or, Make A Joyful Noise HERE assures even more interest.

He can’t pinpoint a specific reason for the recent surge in popularity. “I don’t know. For me, I just made the next record.” There was one significant change; this time the supporting cast was larger than ever before: “With this record I made a very deliberate decision to include everybody who’s around me, and then some…in the past it’s just been some family members are around, some friends are around; ‘Okay, you guys wanna be on the record?’ This time I went to the West Coast, I went to New York City. I had people around the country recording…all different places.

“But in terms of why the audience is different. I don’t know… the music climate is always changing. Some of the people who are involved in this record have had success lately, so I’m sure some people will say ‘Oh, Deerhoof is on this record. I like those guys, let me check these guys out.’ So there’s some of that going on. Certainly with Sufjian [Stevens]. And some other people too.”

Smith has said his music is "too weird for the Christians and too Christian for the weirdoes," but anyone willing to give his music a chance will discover a rich catalogue of distinctive gems.

His earnest but at times strained falsetto voice might catch the first time listener off guard, but like Talking Heads’ David Byrne, or early David Bowie, it’s a character quirk that grows on you.

Strings, horns, assorted percussion, banjos, toy pianos, and an all-ages choir produce a delightful blend that sits somewhere between cacophony and melodious. Incorporating new jazz, new wave, art rock and Appalachian mountain music, the Danielson sound is avant-garde yet accessible.

The visual element is just as distinctive. They’ve performed dressed as hospital orderlies and nurses, with hearts pasted on sleeves, symbolizing the healing power of the gospel. For the Ships tour the group are sporting faux Boy Scout uniforms.

The visual element is just as distinctive. They’ve performed dressed as hospital orderlies and nurses, with hearts pasted on sleeves, symbolizing the healing power of the gospel. For the Ships tour the group are sporting faux Boy Scout uniforms.

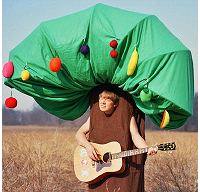

On solo shows he’s performed from inside a paper mache tree that displays nine different types of fruit – “for the nine fruits of the spirit.”

On solo shows he’s performed from inside a paper mache tree that displays nine different types of fruit – “for the nine fruits of the spirit.”

Scripture says we must be like a little child to enter the kingdom of God, and Smith takes that seriously. Many titles – ‘We Don’t Say Shut Up,’ ‘Big Baby’ ‘Cutest Lil’ Dragon,’ ‘Let Us ABC,’ ‘Farmers Serve The Waiter,’ ‘Kids Pushing Kids’ – sound like children’s songs. Some are fairly straightforward, but Smith’s lyrical approach is similar to Captain Beefheart, with wordplay and serious messages hidden under seemingly playful couplets. Like Beefheart, Smith has devised his own musical vocabulary. Songs are sometimes allegorical, sometimes literal. He’s thrilled with the Beefheart comparison; “Oh, I love Captain Beefheart. The chances [he takes]…there is joy there. There is joy in that music.”

There’s no proselytizing or evangelizing. Instead, Smith prefers to point to Jesus, “and let Him do all the hard work. We show and share what little we know.” The songs are not written with a Christian audience in mind. Or any specific audience, for that matter. The words ‘Jesus’ or ‘Christ’ almost never appear in the lyrics, yet everything is faith infused.

Smith went through what he describes as “the usual prodigal son story” in late high school and college. “The weirdest thing is I never doubted that God was real because I had had a spiritual life from as far back as I can remember, of praying and hearing from God, and finding comfort in that. But being a teenager and doing my own thing, it was more that I just wanted to do what I wanted to do. Don’t we all… So going down that road of thinking that I know better, trying to create my own plans, and my own life. And with some questioning of ‘okay, is this just my parent’s thing?’ And never doubting. I remember being pretty out of my mind and wasted and hearing with a very clear voice God whispering ‘I’m still here.’ And instead of my response being ‘Oh wow! You’re real!’ it was more ‘could you just leave me alone for a little while?’” He laughs; “I just wanted to do what I wanted to do. Like any selfish kid.”

Smith went through what he describes as “the usual prodigal son story” in late high school and college. “The weirdest thing is I never doubted that God was real because I had had a spiritual life from as far back as I can remember, of praying and hearing from God, and finding comfort in that. But being a teenager and doing my own thing, it was more that I just wanted to do what I wanted to do. Don’t we all… So going down that road of thinking that I know better, trying to create my own plans, and my own life. And with some questioning of ‘okay, is this just my parent’s thing?’ And never doubting. I remember being pretty out of my mind and wasted and hearing with a very clear voice God whispering ‘I’m still here.’ And instead of my response being ‘Oh wow! You’re real!’ it was more ‘could you just leave me alone for a little while?’” He laughs; “I just wanted to do what I wanted to do. Like any selfish kid.”

Smith grew up in rural New Jersey, and earned a degree in print making at the Mason Gross School Of The Arts – part of Rutgers University.

Higher education opened his eyes to a whole new reality, but didn’t always enjoy the experience; “[I was] going to art school, every once in a while liking some of the things I’m seeing in art history, and being turned off by a lot of it, being forced to read all kinds of things that I didn’t necessarily agree with. But once I discovered what is now considered Outsider Art – Howard Finster and a lot of those guys – that’s the stuff I started getting really excited about, except the professors thought it was not important work at all.” Outsider Art is primarily self-taught artists who work outside of the mainstream. One of the more renowned figures is Howard Finster, a southern pastor who claimed God told him to spread the gospel through his art. In addition to Paradise Gardens, a four acre plot dedicated to displaying ‘all the wonderful things o’ God’s Creation, kinda like the Garden of Eden,’ Finster produced over 10,000 works before his death in 2001). “So there was that dynamic between Howard Finster in Georgia, having God tell him to put all of his tools in the ground and build a giant block radius of artwork versus scholars in Soho writing about artwork. Instead of making stuff, people were just writing about making stuff. I just couldn’t relate to that. So I took a field trip down to Paradise Gardens in Georgia…I think this was ’93. We drove down to Georgia, and just kept driving around trying to find this small town. We stayed in some state park, and asked the Ranger where [Finster’s] place was, and he said, ‘you may call it art, but I call it junk.’ And I knew it was going to be amazing. That was instrumental in shaking me out of my lazy spiritual self, my selfish self, and inspiring me. I would say that moment was one of the key moments for waking me up.”

Higher education opened his eyes to a whole new reality, but didn’t always enjoy the experience; “[I was] going to art school, every once in a while liking some of the things I’m seeing in art history, and being turned off by a lot of it, being forced to read all kinds of things that I didn’t necessarily agree with. But once I discovered what is now considered Outsider Art – Howard Finster and a lot of those guys – that’s the stuff I started getting really excited about, except the professors thought it was not important work at all.” Outsider Art is primarily self-taught artists who work outside of the mainstream. One of the more renowned figures is Howard Finster, a southern pastor who claimed God told him to spread the gospel through his art. In addition to Paradise Gardens, a four acre plot dedicated to displaying ‘all the wonderful things o’ God’s Creation, kinda like the Garden of Eden,’ Finster produced over 10,000 works before his death in 2001). “So there was that dynamic between Howard Finster in Georgia, having God tell him to put all of his tools in the ground and build a giant block radius of artwork versus scholars in Soho writing about artwork. Instead of making stuff, people were just writing about making stuff. I just couldn’t relate to that. So I took a field trip down to Paradise Gardens in Georgia…I think this was ’93. We drove down to Georgia, and just kept driving around trying to find this small town. We stayed in some state park, and asked the Ranger where [Finster’s] place was, and he said, ‘you may call it art, but I call it junk.’ And I knew it was going to be amazing. That was instrumental in shaking me out of my lazy spiritual self, my selfish self, and inspiring me. I would say that moment was one of the key moments for waking me up.”

Returning to school, he decided to combine music with the visual arts. “I had written four or five songs to perform at the art opening for my final thesis show. I had a bunch of sculptures, and I had also written some songs. My brothers and sisters performed them with me live at the opening. And then some of those demos and practice tapes ended up on the first album. Through the songs and through sculpture I was celebrating this kind of spiritual homecoming, which included my reconnecting with my family again and having them perform with me live.”

It’s one thing to sing about your family, quite another to enlist them as fellow artists. His sisters and brothers – the youngest was eleven years old at the time – offered something absolutely unique. The performance – which earned him an ‘A‘ – was recorded, and video of two songs are included on the first album’s bonus disc. It’s clear Smith’s vision was in place right from the start.

Prior to the album’s release, Smith lived at Jesus People USA (JPUSA), a Christian community that works with the inner city population of Chicago. “I’d finished up art school and put together the first album, a cassette of A Prayer For Every Hour. Then I moved to JPUSA, to just kind of take a break from music and take a break from all those dreams that I had. Just go and work and serve, clean toilets and feed the homeless. Wait on God, really.” Part of the motivation was to ensure he was doing music for the right reasons. “Kind of hang up the dreams, and if it’s something the Lord wants, it’ll happen…I was there for six months.”

JPUSA takes the arts – especially contemporary art – seriously. “That’s one of the reasons I went there…I was in this really strange place. I was excited about spiritual things, about these wonderful experiences that I had had recently, and at the same time just super excited about being an artist and a musician and frustrated with the fact that there didn’t seem to be any place that I could have conversations about art and Christ. I just knew I needed to get away and do something. I just finished school…and that was fantastic, but it was still all about puffing up our ego and all about ourselves and our careers. And I wanted to get away from all of that. So I wrote Jesus People, I wrote them this long letter about my frustration with Christianity and art and all this stuff, and they wrote back…I went out there and visited, and went back and lived there for awhile.”

The experience impacted more than his art. “That’s what got me there. They were open to me doing whatever I wanted…turns out I don’t think it was supposed to be about that [art]. I think what it was really about was community, and other lessons. Much more about humility than about refining my craft and sitting around talking about artwork. I think it was much more about when I started cleaning toilets. That’s what it was about.

“Art school had it’s purpose. It was right on time. And then I needed this, too. I think a big part of going there was when I pretended to give up on my dreams; ‘all right Lord, if you don’t want me to do these things that I’ve been dreaming about since I was a kid, then show me what I am supposed to do. Because I want to move forward.’ I think that was the key. Giving up on that dream. I had those cassettes finished, all put together, all hand made, probably fifteen of them. I had the first album ready to send out to all my favorite labels, but I just felt like I wasn’t supposed to send them out, and a couple of months into it I felt like the Lord said ‘Okay, now send them.’ And I was in a different place, you know. And then I got a response.”

After signing with Tooth & Nail, he called up his childhood friend Chris Palladino, who was attending seminary school. Smith said he thought Palladino should play bass with the group. Palladino agreed, even though he’d never played bass before. He later moved to keyboard, another instrument he’d had no experience with.

A Prayer For Every Hour was released on Tooth & Nail in 1995. “I sent that cassette out to all my favorite indie hipster labels that I’d been listening to for years. And none of them responded except for Tooth & Nail, who were kind of a new young fresh independent, but Christian label. And I was pretty nervous about that. I didn’t know much about them. They had a couple of artists that seemed pretty interesting. But the fact that they responded, and said ‘Who are you? What’s your deal? This is really weird, wonderful stuff.’ I respected that. And the fact they were willing to just put it out as is and not make me go into a big studio and try to clean it up…they were just willing to put it out, because it was crazy and weird, and I went with it. I definitely have to respect that. The fact that they had independent distribution back in the day, I was really impressed with that. They would get into all the indie-rock stores.”

Did Tooth & Nail understand what he was doing? He laughs; “I don’t think I understand what I’m doing. I still don’t understand what I’m doing. I think they understood enough that they thought it was really good stuff. The other part of being on a label like that is it also got into the Christian book stores. Which was very controversial, it turns out…”

The reaction from many in the Christian music scene bordered on outright hostility. “There were a lot of people who were really furious with the music, and that Tooth & Nail would sign Danielson – and a lot of really mean Christian press, which was pretty fascinating to me. I kind of enjoyed it, to be honest. Because it wasn’t the lyrics that they had a problem with. It was the music, and to me that spoke volumes. There’s no lyric in there that isn’t biblical. Why are people getting so angry about the music? The kids loved it, but the press was angry. I mean, really mean.

“So we’re getting all kinds of praise from the mainstream and indie press …” – including Spin, the Village Voice, Rolling Stone and The New York Times – “…and the Christian press was just tearing it up.”

(It’s worth noting that on the three previous occasions Canadian Christianity covered the band, the group was highly praised for it’s efforts).

If the lyrics were straight ahead in presenting a distinctly Christian worldview, what was the problem?

“It didn’t sound like Christian music,” said Smith “And what does that mean? It doesn’t mean anything! So I really enjoyed that, I have to say.”

Around that time Smith had a notable encounter at a festival known for alternative-leaning Christian artists, most of which don’t fit the CCM formula.

“I played Cornerstone for the first time – just by myself with two friends on stage. After I finished my show, this guy came up to me with his girlfriend, and wanted to beat me up. And this is a Christian festival. It’s really amazing what was going on.”

For the first few years, audiences didn’t know what to make of Danielson in concert. Having attended a few early shows myself, it was fascinating to watch listeners trying to make sense of what they were witnessing. Was it parody? Were they really a family? Smith touched a nerve, and that confused people. It could be argued that provoking such a passionate reaction simply confirmed he was on the right track. “I though so. They didn’t think so, but I thought so… Clearly we really didn’t belong in that scene. I feel like we just belong in neutral environments, [such as] a club or a bar where Christians can come out.”

Danielson would return to Cornerstone repeatedly over the next few years, but for the most part church-related performances were rare. “We used to get invited into churches more, and now we really don’t get invited to too many. Our policy is we’ll play wherever we’re invited. I’m not against that. I just think what we’re doing belongs in these [other] environments – and there’s plenty of people who understand where we’re coming from. We don’t do alter calls or anything. We pray before every show. All of us pray together that God bring the people He wants to bring, and that the Holy Spirit come and fill us and fill everyone there, and change people’s lives. But that’s on the spiritual level. I’ve had people come up to me and say ‘I was suicidal, and I got your record and it changed my life.’ That’s pretty incredible stuff, but that had nothing to do with me. The Lord used the album. And it’s great, because it takes all the pressure off me.”

He’s happy to see believers attending shows in clubs: “It’s good for Christians to come out, and see that Satan doesn’t rule the bar. This is where people go when they want to hear music, or they’re lonely. It’s where people go. It’s a place where there’s a stage and there’s microphones, and people are used to going to see shows there…It’s just where there’s music everyday. So if you’re not bringing the goods, you’re not going to be playing there.”

As far as the temptations inherent in hanging out in such establishments, it’s no worse than anywhere else. Even the church?

“Absolutely. In fact, I would argue – sometimes we play Christian events, and it’s pretty crazy, because there’s so much money backing these things. There’s hotel rooms and buffets, and all kinds of crazy stuff. Where in the real mainstream life of touring that’s not the way it is. You’re not getting pampered like that. You just show up, and you eat your pizza. It’s not that that’s better necessarily, but there’s a non-reality, too. I remember feeling like, ‘Wow, we’re being treated like rock stars at this church, and I feel very uncomfortable with this. We’re just here to play some music.’

“I’m sure there are a lot of good intentions there, [but] what’s the solution? How do we create this subculture that we want to create? And I actually think, the best thing that they could do would be to start a bar. And I don’t mean that as some kind of controversial statement. I literally mean, start a club that serves some wine and some beer, with a really nice PA, and people will come. And there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s a social place.”

Meanwhile, they were picking up more and more fans. In addition to the positive press, Rick Moody – author of The Ice Storm and Garden State – wrote about the band in a collection of short stories and essays. Jeff Buckley had raved about the band shortly before his untimely passing in 1997, and they appeared at All Tomorrow’s Parties in 2002, a prestigious concert series held annually in England. They even had a John Fluevog shoe (Familevog) named after them.

A Prayer For Every Hour was followed by Tell Another Joke At the Ol Choppin’ Block in 1997. They worked with producer Kramer, a legendary New York City figure who made his name with Bongwater and Galaxie 500. While the debut was decidedly lo-fi – it was all four track recordings – the sound quality took a huge leap forward this time around. A highlight was ‘Ye Olde Battleaxe,’ a tribute to motherhood; “Mother’s be bein’ the bravest ones/the real ones/the smart ones…my dad says when heaven comes/my mom she’ll be in that front row/waving back to my dad.”

From 1998, (Alpha) included ‘A Meeting With Your Maker;’ “been to the halo house/let me tell ya/it’s all pretty there/there’s a fellowship of love/happening in this town/foreign exchange at high noon/all that matters will be there.”

A companion disc, (Omega) was released the following year. Both were credited to Tri-Danielson!!! and introduced “the three branches of Danielson;” Family, Brother, and Ship, a concept that has continued through to the newest release.

Meanwhile, Tooth & Nail was becoming more and more successful, which didn’t bode well for Smith; “They turned into a much bigger label…what I would consider more of a major label. And that’s where I think we all agreed it’s best for Danielson to stay on an independent.” He signed with Secretly Canadian – an uber hip label whose roster includes critical faves Antony & the Johnsons. The label showed genuine support, reissuing all of the band’s previous albums. A Prayer For Every Hour was given a deluxe two-disc treatment.

Steve Albini (producer of the Pixies, Nirvana and Chevelle) was on board for 2001’s Fetch The Compass Kids, their first album for the new label. Albini brought out the best in the band in songs like ‘Hammers Sitting Still,’ which dealt with Daniel’s job as a carpenter; “…held back and frustrated/insecure and I’m annoyed/All my bubbles have been bursted and I’m left with shoulders bruised/Work is robbing me of living/they were right about my dreams/My debts building while I stand here/should this even be a song?”

Brother Is The Son, from 2004, was a solo album in name only. Credited to Brother Danielson, all the usual players were on board, but the focus was on individual identity as much as community. ‘Physician Heal Yourself’ was a study in frustration; “I can’t understand the ways of my Lord/When I try and try with my mind as a mere man.”

Smith mentored Sufjan Stevens, a fellow believer whose Illinois topped many critic’s annual best of lists last year. In addition to performing with Danielson on stage and in the studio (including Ships), Stevens brought in Smith to produce his 2004 release Seven Swans. Not surprisingly, Stevens’ methodology is deeply indebted to the Danielson approach, from having his band perform in matching outfits to releasing multi-part ongoing concept albums. There’s a strong bond between the two, based on mutual respect and shared visions. It could be argued that Danielson paved the way for Stevens’ success. Sufjan Stevens – admittedly a more melodic version – was embraced by a mainstream audience almost immediately.

Stevens no longer talks on record about his faith. I asked Smith if was a case of being burned too many times. “Yeah, I think so. And I understand where he’s coming from. I mean, you say the word Christian, and that means a hundred things to a hundred people. It could be a political statement. It could mean all kinds of terrible things. I think he just doesn’t want to deal with it. I’m not going to speak for him, but my guess is the music answers any of those questions.”

The official Danielson bio states ‘tuning into their frequency can be as deeply rewarding in a literary-visual-musical way as with canonical acts such as Sun Ra, Parliament and David Bowie.’ All were major influences, but Daniel claims his father as his biggest inspiration: “I remember listening to the Beatles when I was five. Listening to Revolver. And knowing. I have to thank my parents for not being afraid.” They instilled an outlook refreshingly free of fear; ”One of the biggest ways they’ve influenced us all is to not let fear run our faith. Fear is not the root of our faith. Fear is the opposite of love. If we truly believe these things, if we believe that God is in control, then we’re not running and hiding all the time. To me that’s a completely different world view. There’s a couple of world views in the church. One is to hide away, and wait for Christ to come back. Which is part of the ‘have them come to us’ mentality; you know, we’ll be happy to share the good news – just have them come to us. A world view which is not rooted in fear, but rooted in love, and confidence in that love, [is] where we can go out into the world – whatever that means – and share the good news. And when I read what Jesus did, that’s exactly what he did. But that takes faith. That takes serious faith. We look around, and if we’re not careful we get hung up with the news headlines, which could scare anybody. So I was allowed to listen to the Beatles when I was young. We were listening to Bob Dylan and the Beatles. And that’s a great foundation. That sets the bar right there.”

For a short while things were different in the Smith household: “There was a wave in the early mid 80s, preachers coming through the churches were talking about Satan loving rock ‘n’ roll, and backwards masking and all this stuff, and I remember being ten or twelve, just cringing, and not believing it at all. And my parents – my dad – he gave it a try. He tried the Christian music thing, and said ‘that’s all you’re allowed to listen to’ for awhile.” (Smith points out he did discover Larry Norman as a result, “which was incredible”). “But after a year of going to Christian concerts my dad was like, ‘you know, you don’t have to…’ and it’s not a put down to anybody, because I think everybody is doing the best they can. And again that’s the world view.”

He brings up an incident from his formative years that illustrates the fear-based mindset; “I’ve told this story a million times, but I think it still speaks volumes: I went to the local Christian book store looking to buy the U2 album War, and the owner just kept showing me other bands that sound like U2. I was saying, ‘no no, these guys are Christians, I wanna buy this album.’ And he just wouldn’t sell it to me, until I insisted. And he did have it. But he wanted me to buy something on a Christian label. I guess I was determined and rebellious at age twelve. I don’t know, but it just irritated me, because I knew this was a great album, and that’s what I wanted.” Two decades on, U2 continue to proclaim their faith in a manner that appeals to Smith. “Yeah, they’ve been pretty bold lately. Amazing.”

Early in their career U2 considered disbanding after being advised by concerned church members that the music industry was no place for believers. Thankfully, that world view is no longer as popular. “I think right now there’s a whole generation of younger people who are coming out of this place that we’re talking about, where for a couple of decades it was understood that you needed to hide away if you were a Christian. That’s the way it was. It just seems like God’s been saying ‘Stop! Stop!’ for a long time, but our religious ways take a long time to get broken down…I’m excited about seeing Christians working in the mainstream marketplace. And not as a propaganda tool. Not as ‘outreach,’ [or] any of that stuff. Just being artists, and being honest with who they are. Any artist should be honest with where they’re coming from. And I think the Christian has the advantage because we can go straight to the Creator and say ‘Hey, can you give me some good ideas, because I don’t have any…’

“Using music for propaganda, especially by the church, does a great disservice to the listener. And everybody sees through it. Because they should see through it. We should just do what we’re made to do. If we’re doing what we’re made to do, it’s not going to come off phony or suspicious.”

Smith is always open about his faith, yet rarely comes under criticism from the mainstream press. When it has occurred, he’s philosophical. “I’m not going to deny that there are still a lot of people who won’t give us a chance because they hear that we’re Christians…To me that’s almost some of the fallout of this cultural change. It’s not as extreme as it was ten years ago…People are more open [today]. Also, as people finally check us out, they don’t feel like we’re trying to convert anybody. I’m just trying to tell the truth. I believe only the spirit of God can convert people. Only the spirit of God can change people. I don’t want to talk anybody into anything. That’s not what it’s about. It’s not about convincing people… or manipulating or brainwashing. It’s gotta be a spiritual experience, or (else) it’s just a religious experience.”

Smith is very aware of the folk tradition, and is particularly fond of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, a legendary collection of early 20th century American rural blues, gospel and popular recordings that first appeared in the 1950s. He relates to the way the music was originally created. “Just the organic process. These people are writing songs. Why? Because they’re sitting around the campfire, or sitting in the cabin, and wanting to tell stories. And wanting to all sing together. And that’s certainly part of our background. Our Dad has been writing gospel folk songs since the early sixties. We grew up playing toy instruments singing with him in the living room, having our own little church services. Growing up with our mom making our clothes – handmade – and always encouraging drawing and artwork. That’s certainly a part of where we come from. And spiritual life plays right into that. To me there’s no division.”

The family patriarch is Lenny Smith, a worship leader best known for writing ‘Our God Reigns.’ First popularized in the mid-seventies, the song has gone on to become an enduring classic. It was even played from the Popemobile when Pope John Paul II visited North America in 1999.

Lenny was studying for the priesthood when he heard Bob Dylan, and it turned his life around. Meanwhile mother Marian was headed towards life as a nun – she had designed modern habits for the sisters – when things clicked with Lenny. They were married in 1970, and soon after, Daniel arrived. Rachel, Megan, David and Andrew followed. As Lenny explains, “We were happy and wanted more kids. More people in the party…”

And that same spirit infuses the band. Over the past few years wives and husbands have come on board; Daniel’s wife Elin and Chris’ wife Melissa play with the group, and when Megan married a seminary student, he was promptly drafted as bass player.

Daniel met Elin when he was living at JPUSA. She was from Norway, and when she returned home he sent her a violin. She came back, they were married and today they have two young daughters.

In addition to the musical endeavors, Elin, Rachel, Megan and Melissa have Mamma Made, a clothing line for toddlers, and Daniel and Lenny run a carpentry business together.

But there’s more; “I have a record label called Sounds Familyre, which is kind of just the way to put out records by all our friends.” The eclectic range of acts includes Lenny – whose album was recorded over 7-8 years, and features most of the family performing songs from throughout his career – Half-Handed Cloud, Woven Hand, and the Singing Mechanic, among others.

He has no time for the rock lifestyle. “Rock ‘n’ roll culture. I can’t stand that idea, that cliché of you’re only relevant when you’re young…That rock ‘n’ roll mentality of live fast and die young. All my favorite visual artists or jazz musicians, their goal is to get better as they get older, whereas the tradition of rock ‘n’ roll is to do it before you get wrinkles. I can’t stand that mentality. I want to keep making stuff until I’m eighty.” He’s puzzled as to why “so many amazing musicians become bland and boring as they get older. [There’s] very few exceptions in rock and pop history.”

At the head of Smith’s short list of pop musicians who haven’t burned out is Bob Dylan; “He’s my favorite, by far. I believe Dylan is the most important person in rock history so far. Because he won’t go away. His last couple of records are amazing.

I’m just so fascinated by him. At first I wasn’t into any of the 70s or 80s stuff, or any of that, and I only wanted to listen to the early acoustic stuff. No doubt there’s some clunkers in the 80s, but it’s hard to know if it’s just bad production or bad songwriting. Look how many records he’s made, and it’s always interesting. I’m fascinated by him, and I think he’s a genius.”

Smith is a self-described “jazz hack,” with a fondness for “that crazy free jazz stuff…stuff that’s experimental in some way.” Favorites include Thelonious Monk – particularly his solo piano work, Ornette Coleman, and John Zorn.

Historically, musicians fueled by ardent spiritual beliefs – like Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, U2 and John McLaughlin – produce music that goes well beyond their chosen genre. Danielson shares that transcendent quality.

I wondered if other performers are shocked when they realize he’s on the level about his faith. “Yeah. For years people have been wondering if we’re a joke. In every interview we’ve ever done I’ve said we’re not a Christian band, and we’re totally serious. So after awhile people hear that, and give the music a chance. And when people come out to the shows they can see that we’re completely serious. People confuse joking and joy. Just because we’re smiling and having fun and there’s joy, that doesn’t mean we’re joking. There’s plenty of humor and jokes, of course, but it’s not a joke. I love that gray area. That fine line.”

Ships’ title conveys multiple meanings, all rooted in relationship. “It came out of sonship, daughtership…our identify with each other, brothers and sisters, our heavenly father and our maker, and us as all children. Relationship has been at the core of Danielson from the beginning. When I wrote Tri-Danielson, the idea was to talk about the three and the one, the concept of three and one, using Danielson band as an illustration for it. Danielson Famile was one band, Brother Danielson was kind of a solo, singular identity, and then Danielsonship was this idea of community, and creative community and we’re all in the boat together idea. So following the Tri-Danielson I did a full length of each moniker. A Danielson Famile album (Fetch the Compass Kids), a Brother Danielson album (Brother Is to Son), and then the new Danielson record Ships is the fulfillment of all that in a lot of ways. Just talking about studying relationships, spiritual ones, and family, and then actually doing it. Including 38 – 40 people on the record. Making that part of the point.”

Ships’ title conveys multiple meanings, all rooted in relationship. “It came out of sonship, daughtership…our identify with each other, brothers and sisters, our heavenly father and our maker, and us as all children. Relationship has been at the core of Danielson from the beginning. When I wrote Tri-Danielson, the idea was to talk about the three and the one, the concept of three and one, using Danielson band as an illustration for it. Danielson Famile was one band, Brother Danielson was kind of a solo, singular identity, and then Danielsonship was this idea of community, and creative community and we’re all in the boat together idea. So following the Tri-Danielson I did a full length of each moniker. A Danielson Famile album (Fetch the Compass Kids), a Brother Danielson album (Brother Is to Son), and then the new Danielson record Ships is the fulfillment of all that in a lot of ways. Just talking about studying relationships, spiritual ones, and family, and then actually doing it. Including 38 – 40 people on the record. Making that part of the point.”

With such a considerable supporting cast, it’s testament to Smith’s ability that his singular vision comes across undiminished throughout the disc. Songs like ‘Did I Step On Your Trumpet’ are catchy as can be. In the very best sense, Ships is essentially a pop album. Melodies linger, and choruses that won’t quit attest to a latent pop sensibility that’s getting stronger every time out. Like Captain Beefheart’s Clear Spot, Smith has created a work that retains all that made his earlier efforts so special, yet is palatable to the novice listener.

‘My Lion Sleeps Tonight,’ resonates with the story of the prodigal son; “My stomach is filled with pig pods/No longer worthy to be called your son/But Pappa runs to me/And his arms/Around me does throw.” The sound is muscular, with distinctly British art rock leanings. ‘Time, the Bald Sexton’ brings to mind Peter Gabriel era Genesis.

Danielson: A Family Movie (Or, Make a Joyful Noise Here) offers a fascinating look at Smith’s personal and creative journeys. “I’m very pleased. It was something that I wasn’t interested in at all when the director approached me, because I didn’t know [him], and we try to stay fairly private – my family and friends – [so] I wasn’t interested in a movie at all.”

Danielson: A Family Movie (Or, Make a Joyful Noise Here) offers a fascinating look at Smith’s personal and creative journeys. “I’m very pleased. It was something that I wasn’t interested in at all when the director approached me, because I didn’t know [him], and we try to stay fairly private – my family and friends – [so] I wasn’t interested in a movie at all.”

The film’s director, JL Aronson, first came across Danielson while working as publicist for the Knitting Factory, a music club in New York City. In the film’s press materials, we’re told that Aronson was “drawn to and perplexed by this strange, beautiful music that seemed so foreign to his own weltenshuang” Filming commenced in the spring of 2002.

“JL assured me that he was a fan, so he followed us around for about five years, and it turned into a wonderful story, I have to say. It actually helped me, just watching it, to take a step back at what we’ve been doing for the past ten, eleven years, which as a policy I don’t ever want to step back and look at myself. So it’s kind of given me a little bit of a clearer idea of how to approach the new record and it’s interesting that the film kind of taught me some things about myself.”

After well-received festival showings this past summer, the film will have a limited theatrical release in December, with a DVD release slated for spring 2007.

Twelve years in, Smith is happy, but hardly ready to slow down. “I’m really pleased now. I feel like Danielson is in a place where I can do anything. I’ve got this wonderful arsenal of friends and family ready to do some more recording.

“Over the next year I’m going to continue this seven inch series that I started. I’d made a long list of people I wanted to be on Ships. The record got full fast. There was a bunch of other people I wanted to work with who didn’t make it on the record, so I think I’m just going to continue working with all these people going down the list, I’ve done three seven inchers so far, with some of these folks, and I’m going to keep going.”

Smith is equally excited about upcoming releases for Sounds Familyre: “We’ve got a bunch of unfinished records that I’m trying to mix and produce.” And finally, he plans on pursing another dream; “I miss working on the visual arts, so I’m hoping to get back into that. There’s a gallery in New York that’s really excited about my stuff – I’m working with them.”

Of all the terms used to describe Daniel Smith, ‘weird’ just doesn’t seem to apply. In light of the increasing work load, the term Smith himself used is straight ahead and to the point; “really busy.”

© John Cody 2006