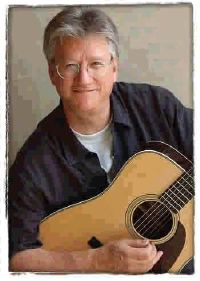

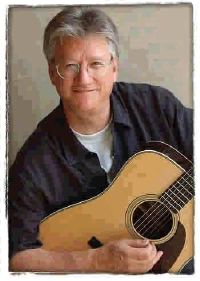

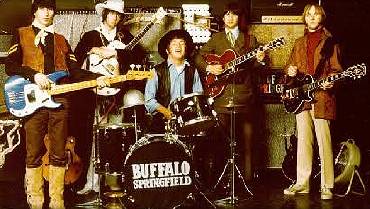

As vocalist and rhythm guitarist for the Buffalo Springfield, Richie Furay played an integral part in one of most important bands of the 1960s, singing his own songs as well as many written by fellow members Neil Young and Stephen Stills.

After Springfield folded, he formed Poco, and helped kick-start the country/rock scene that continues today.

His next band, Souther-Hillman-Furay, included Al Perkins, a legendary steel player who has been described as a ‘Christian Johnny Appleseed.’ Focused completely on his career, Furay was hesitant to the idea of working with a believer, who could only slow things down. He relented, on the condition that Perkins refrain from talking to him about Jesus.

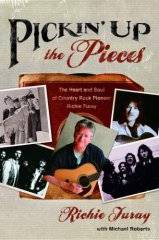

Thirty years later, as Pastor of a Calvary Chapel in Colorado, Furay has a decidedly different outlook. He recently released his autobiography, along with two new CDs.

He spoke at length about his life and career.

BEGINNINGS

When teen idol Ricky Nelson sang ‘Be Bop Baby’ on a 1957 episode of The Ozzie and Harriet Show, the impact was particularly evident in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where Richie Furay’s life was changed forever. Still in the seventh grade, Furay was taken with the sound, and immediately started his first band.

A few years later, along with the rest of the country, he was bitten by the folk bug.

The most popular act – the one that kick-started the whole folk era – was the Kingston Trio. Furay cites them as one of his biggest influences; “They sure were…they really took off and struck a chord with me when John Stewart joined the band [in 1961]. John had a passion for a lot of different things and he wrote about them, and of course folk music is a type of protest music – social causes. And back then I was way over there – I’m a lot more conservative now than I was back before I became born again, but at the time, I really loved that band, [they] had a tremendous influence on my life.”

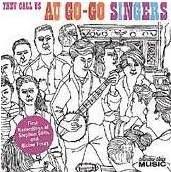

Attending Otterbein College in Westerville, Ohio, Furay formed his own trio – the Monks – during his junior year. After a trip to New York City in 1963 with the school’s choir, all three dropped out and moved to Greenwich Village, where they ended up joining the newly formed Au-Go-Go singers, a nine-piece folk revue. Furay was particularly impressed with one member of the group; Stephen Stills. The two struck up a friendship and were soon sharing an apartment. The group recorded one album, They Call Us Au Go-Go Singers which is more notable as being Stills and Furay’s recording debut than for the music.

Attending Otterbein College in Westerville, Ohio, Furay formed his own trio – the Monks – during his junior year. After a trip to New York City in 1963 with the school’s choir, all three dropped out and moved to Greenwich Village, where they ended up joining the newly formed Au-Go-Go singers, a nine-piece folk revue. Furay was particularly impressed with one member of the group; Stephen Stills. The two struck up a friendship and were soon sharing an apartment. The group recorded one album, They Call Us Au Go-Go Singers which is more notable as being Stills and Furay’s recording debut than for the music.

Even if it had been anything special, radical changes were just around the corner.

The Beatles had arrived, players were plugging in, and the folk scene died almost overnight. “Very, very quickly. John Sebastian and those guys were starting to play electric music down in the Village, which just a year before had been Bob Dylan and Patrick Sky and Tim Hardin and those guys, but the next thing you know, the Lovin’ Spoonful are playing electric guitars, and it’s a whole different scene. And it changed almost overnight.”

Disillusioned, Furay left New York and took a job at Pratt & Whitney, an aircraft manufacturer based in Connecticut.

He stayed loyal to folk music, returning to audition for the Chad Mitchell Trio, a gig that John Denver ended up getting. “I auditioned…because it was still folk music, and I thought that was it. I thought that was where it was all at – until I heard the Byrds record.”

The change in heart came by way of a visit from former Village cohort – and future Byrd – Gram Parsons. Parsons had his own folk trio, the Shilos, and was tight with Furay and Stills. He brought along a copy of the Byrd’s debut album, Mr. Tambourine Man.

While the rest of the world was caught up in Beatlemania, for Furay, it was the Byrds.

“To me their sound was certainly as distinct and unique as the Beatles. And when Gram brought me that album it was like; ‘I’ve gotta get out of here right now.’ Because I really hadn’t heard anything like it. It was a brand-new thing. We were all wooden guitars, and it was strictly acoustic for us – and with the electric sound, and particularly Jim or Roger’s [McGuinn] twelve string – it was just an incredible, different, fresh sound. And I thought ‘This is new; this is something I want to do…I could identify a little more with them [than the Beatles], from the folk standpoint. But boy, I’ll tell you what; when I heard it, it was like ‘I gotta get out of Pratt & Whitney!’

BUFFALO SPRINGFIELD

Inspired, he called his old roommate, who was now living in Los Angeles. “When I called Stephen from Connecticut, I said ‘hey man, what’re you doing out there? You making of any music?’ He said ‘come on out – I got a band together, we just need another singer and we’re ready to go.’”

Furay headed out west, where he discovered things were not exactly as Stills had described – the band only existed in Stills’ mind at that point – in reality, it was just the two of them.

Neil Young topped their list of potential recruits. Stills had met him while on tour in Canada, and the two hit it off immediately, agreeing they would work together at some point in the future. Young showed up at Furay and Stills’ apartment in New York soon after. Stills had moved to California by then, but Young hung out with Furay and took the opportunity to teach him one of his earliest compositions; ‘Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing.’

They both knew Young was right for the band. The only problem was tracking him down. Unbeknownst to either of them, Young and his bassist Bruce Palmer were already in L.A., having driven Young’s 1953 Pontiac hearse – affectionately dubbed ‘Mort’- from Canada attempting to locate Stills and Furay. In a moment that’s gone on to become rock ‘n’ roll legend, while stuck in a traffic jam on Sunset Boulevard they spotted Young’s vehicle traveling in the opposite direction. Realizing the odds of a hearse with Ontario license plates not being Young, they gave chase.

Within a few days Dewey Martin, a drummer who had played behind the Everly Brothers and country legend Patsy Cline, came on board, and the band was complete.

Within a few days Dewey Martin, a drummer who had played behind the Everly Brothers and country legend Patsy Cline, came on board, and the band was complete.

One week later, on April 11, 1966, they played their first-ever show, a warm-up date at the Troubadour in Hollywood, before heading out on a six date tour with the Byrds.

Furay played rhythm guitar while Stills and Young battled it out with dual leads. All three sang.

Richie had the best voice. A strong tenor, he sang lead on seven of the twelve songs on their self-titled debut, including Young’s ‘Flying On The Ground is Wrong,’ which the Guess Who covered in Canada, and Stills’ ‘Sit Down, I Think I Love You,’ which was a hit by the Mojo Men.

He didn’t write anything on the debut disc, but by the second album, 1967’s Buffalo Springfield Again three of his songs were featured, including ‘A Child’s Claim To Fame’ one of the earliest fusions of country and rock.

He didn’t write anything on the debut disc, but by the second album, 1967’s Buffalo Springfield Again three of his songs were featured, including ‘A Child’s Claim To Fame’ one of the earliest fusions of country and rock.

Last Time Around was the band’s third and final album. Put together as they were falling apart, it was left to Furay and new bassist Jim Messina to assemble a cohesive package. Furay had four songs on the disc, included one of his most endearing compositions, ‘Kind Woman,’ a love song to his new wife, Nancy. He also sang lead on the band’s final single, Young’s ‘On The Way Home.’

Last Time Around was the band’s third and final album. Put together as they were falling apart, it was left to Furay and new bassist Jim Messina to assemble a cohesive package. Furay had four songs on the disc, included one of his most endearing compositions, ‘Kind Woman,’ a love song to his new wife, Nancy. He also sang lead on the band’s final single, Young’s ‘On The Way Home.’

As a writer Furay’s role in the band was similar to that of George Harrison in the Beatles, where the other two songwriters were so good that his work was often overlooked.

There’s no resentment on his part.

“I look at my relationship with Stephen, and Neil in particular, and I think I let those guys who were – as far as I’m concerned – a little more advanced in what they were doing, and I tried to take lessons from them and learn from them and just observe. It wasn’t that I wasn’t writing, because by the time our second Springfield album came out I was definitely making some contributions. But I appreciated what those guys were doing, [and] it was kind of fun just to stand back and watch ‘em try to up the other one.”

With two legendarily volatile personalities, tempers often erupted. Furay downplays the more dramatic episodes, believing the pressure was actually a positive characteristic. “I think it was. I think people have made a lot of malarkey over the fact that these guys were always bickering and fighting. That’s not really true…I don’t know where that figment [comes from]… I mean, let’s face it, Stephen and Neil did have a competition going. There’s no doubt about it. And I think that it probably led to some of why Neil was in and out and gone as much as he was. But as far as them fighting or bickering, I really don’t know where all of that stuff [comes from].”

The group’s management team – Charles Greene and Brian Stone – could be problematic. The duo had made their reputation as managers with Sonny and Cher. “They came on the scene and obviously their big claim to fame that sold us was Sonny and Cher.”

Their hands-on approach frustrated the entire group; “You know, I think it was a problem. I don’t know if it was to the degree that it’s been blown up to, but I wish that Charlie and Brian had maybe left us alone in the studio. They had their egos, and they were gonna be the producers of our records, and I wish that they had left us alone. And then it got to be where they just really did not know how to mediate between the members in the band. I think if there was anyone that was actually instrumental in any kind of wedge or whatever that went in between Stephen and Neil, it came from the management, because they would play one guy off the other; ‘You’re the guy, man, you know if the band doesn’t have you, then there’s no band at all.’ You know? It’s like; ‘You’re the guy that really makes it work.’ And so they were feeding those guys that line, and you start to believe the press after awhile, and then you start going off and doing other things.”

In just over two years, it was all over.

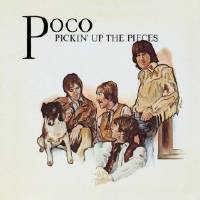

POCO

Out of the ashes of Springfield, Furay formed Poco in the summer of 1968. He brought along Jim Messina and pedal steel player Rusty Young, who they had used on a Springfield recording session. Drummer George Grantham and bassist Randy Meisner rounded out the band.

Their debut album was released a year later. With the charts full of heavy acts like Iron Butterfly, Blue Cheer and Vanilla Fudge, the upbeat harmony-laden songs and distinct country flavor was a breath of fresh air. Outside of one instrumental number, Furay wrote or co-wrote every song on the album. It received a rare 5-star review in the Rolling Stone Record Guide.

Critical acclaim and a solid reputation for their tight, energetic live shows didn’t translate into sales. Too country for pop radio, and too pop for country radio, they were ignored across the dial.

Meisner was gone by the time the album was released, first to work with Furay’s old hero, Rick Nelson, then as a founding member of the Eagles. Messina lasted a few more albums before joining Kenny Loggins for Loggins and Messina, one of the most popular duos of the seventies.

Meisner was gone by the time the album was released, first to work with Furay’s old hero, Rick Nelson, then as a founding member of the Eagles. Messina lasted a few more albums before joining Kenny Loggins for Loggins and Messina, one of the most popular duos of the seventies.

Glenn Frey was a fixture at the band’s early rehearsals, soaking up ideas he would use when he formed the Eagles a few years later. Poco blazed the trail, but the Eagles hit the mother lode with a more commercial version of Furay’s vision. When they replaced Meisner in 1977, they brought in Timothy Schmidt, who had been Meisner’s replacement in Poco.

Furay was long ago resigned to the fact that The Eagles sell millions and Poco is still a cult band; “What really frustrates me most is the recognition. I don’t think that the bank account makes any difference, but the recognition, the influence – I think the world is so caught up in ‘who I heard on the radio yesterday.‘

“You know – when I had Glenn Frey sitting in my living room listening to me put it together – I know the influence that I had. And yet, when I went to a concert of theirs once it was [announced] ‘And Richie’s in the audience from Buffalo Springfield.’ Well, doggone it, man. You know what? I remember you sitting in my living room when I was putting Poco together. So let’s call it what it is. It’s hip to mention Buffalo Springfield – and let’s not take anything away from the Springfield. I mean, Stephen and Neil went on to have tremendous careers. I don’t know where or what my career would have been had I kept plugging away and sticking it out, but at the same time, those guys had tremendous careers and tremendous influence on American music. But I think Poco had an enormous influence. And yet, they’re just overlooked because we never had the radio success.”

Another reason Poco were overlooked was the lack of drama. There was little to write about, except the music. “That’s right,” he laughs; “there wasn’t enough garbage to turn up.” Chris Hillman has said he gets frustrated that articles on the Flying Burrito Brothers invariably focus on Gram Parsons – who died of a drug overdose in 1973 – even though he was just as responsible for the band’s sound. “Chris has a very definite point there. Let’s face it, Gram was a talented guy. He was the one that brought the Byrds record up to me at Pratt & Whitney – it was Gram. So our relationship goes back a long ways.”

Another reason Poco were overlooked was the lack of drama. There was little to write about, except the music. “That’s right,” he laughs; “there wasn’t enough garbage to turn up.” Chris Hillman has said he gets frustrated that articles on the Flying Burrito Brothers invariably focus on Gram Parsons – who died of a drug overdose in 1973 – even though he was just as responsible for the band’s sound. “Chris has a very definite point there. Let’s face it, Gram was a talented guy. He was the one that brought the Byrds record up to me at Pratt & Whitney – it was Gram. So our relationship goes back a long ways.”

Ironically, while Parsons’ visit brought about Furay’s return to music, Parsons himself was on his way to Harvard, where he would study theology for a semester.

In 1968 they tried to put a band together.

“When we put Poco together, and he was putting the Burrito Brothers together, we couldn’t come up with a group where I wanted to give up this guy, and he wanted to give up that guy. And so we had two bands.

“Again – I see the Lord’s hand at work in my life before I ever had a clue, or even knew what was going on, because Gram was just a little too far off…he was over the edge. Though I liked him, appreciated him, [and] thought he was a talented guy, I knew it wouldn’t work in a band situation.”

The title track to Furay’s sixth and final album with Poco, Crazy Eyes – which he had written four years earlier – was about Gram, and released less than a month before Parson’s death.

It was a sad ending to a brilliant talent.

Hillman has commented that it wasn’t just Parsons – everyone over-indulged at the time – and he counts it a miracle that he didn’t succumb himself. Furay readily agrees. “I know from my past experience, I can say the same thing.” As far as why Parsons died and he was spared, he’s at a loss, although he believes Gram might still be with us today had he listened to his heart instead of his demons; “Finally got him. Finally got him, man. What a shame.”

Some of the players who survived the scene and came to faith are not the ones he would have expected. “Oh boy. Sometimes it does surprise me – like with Mark Volman.” A legendary figure in the L.A. music scene, Volman sang with the Turtles, Frank Zappa, and Flo and Eddie. He’s currently an Adjunct Professor at Belmont University in Nashville. “It really does surprise me that he is a born again believer. Mark’s a born again believer! And at one point in time I was thinking this will never happen, and of course it did. So with situations like that, it just blows my mind.”

When I spoke with Volman for an upcoming article he was surprised to learn of Furay’s feelings, and suggested that if anything, Furay might be amazed by the fact he had managed to survive years of drug abuse and live long enough to become a believer. On hearing Volman’s comments, Furay readily agreed; “I guess I’m amazed that anyone would come to faith – knowing what the Lord had to do to get a hold of my heart. God’s grace is an amazing thing, and I’m just truly thankful for Mark’s coming to saving faith. His comment just underscores what I was probably thinking – that he lived long enough to become a believer.”

“But it just breaks my heart with others that I’ve had an opportunity to really verbalize my faith – as well as live it – for the last 30 years, and it just doesn’t mean a thing to them.”

SOUTHER-HILLMAN-FURAY

In 1973 Furay was enticed away from Poco by industry mogul David Geffen, who had helped shape the careers of the Eagles and Crosby, Stills and Nash. Geffen wanted to replicate the success with a ready-made supergroup, and paired Furay with L.A. singer/songwriter J.D. Souther and former Byrds and Flying Burrito member Chris Hillman. On paper it looked like a surefire hit, and Furay was ready to finally grab the brass ring.

In addition to the considerable talent upfront, they got the finest players for their backing band, including drumming legend Jim Gordon, Al Perkins on steel, and Paul Harris on piano. But it wasn’t enough to make it click. “Lots of times it’s not. I mean, look at the Eagles; they’re not technicians, but they make good records, because it all just happened to flow together. With us, we had the best musicians going. And then Chris was playing bass, and J.D. and I are adding our parts. But what looks good on paper doesn’t always work out.”

Hillman had played with him in the Burrito Brothers and Stephen Stills’ Manassas, and insisted he was right for the band. But Furay didn’t like the idea of working with a Christian. “I thought he was going to be a roadblock because there was a little sticker on his guitar – a fish on his guitar that says ‘Jesus is Lord.’ So I did not want Al in our band at all. And what can I say – six months later, he led me the Lord. So God was at work there.”

Hillman had played with him in the Burrito Brothers and Stephen Stills’ Manassas, and insisted he was right for the band. But Furay didn’t like the idea of working with a Christian. “I thought he was going to be a roadblock because there was a little sticker on his guitar – a fish on his guitar that says ‘Jesus is Lord.’ So I did not want Al in our band at all. And what can I say – six months later, he led me the Lord. So God was at work there.”

The prevailing attitude during the era was that anything was possible; that love would conquer all. “Well, that was definitely the love, peace, dove [era].” Furay laughs. “I mean, look at John Lennon; ‘All You Need Is Love.’”

And would following that sentiment necessarily lead one to God?

“I think one needs to determine who – not ‘what’ – but who love is, and as the Bible says ‘God is love.’ Then it gets down to the defining of ‘who is God.’ So it runs a whole gamut of questions that one has to ask. I mean

“I think one needs to determine who – not ‘what’ – but who love is, and as the Bible says ‘God is love.’ Then it gets down to the defining of ‘who is God.’ So it runs a whole gamut of questions that one has to ask. I mean

– yeah – it should lead right to the God of the Bible, but I’m not sure that it does, because so many people have a misconception of the God of the Bible as this heavy ogre.”

In many cases, what they’re rejecting isn’t even the God of the Bible. That was certainly Furay’s experience; “Being in the scene, it took me I don’t know how many more years for Al to really reach me, and even then, I was saying ‘don’t even mess with me man, I don’t even want to hear from you.’”

Furay became a Christian in the summer of 1974.

The night before, two fans approached him at a Souther-Hillman-Furay concert and told him they had just accepted Christ after talking with Perkins. His response was to say that was great for them, but he had many other things in his life he needed to accomplish “before I could do anything like that.”

He may have appeared together on the outside, but things were hardly rosy – his marriage was falling apart, and with a brand new daughter, he was terrified it was over. As he relates in his book, things did turn around for the couple, but it took awhile.

One habit that changed in an instant was drugs. “Once I accepted the Lord, I never looked back or ever even had a desire really for the drugs that we were doing.”

FIRST SOLO ALBUM

Anxious to share his newfound faith, when Souther-Hillman-Furay broke up, Furay decided to go solo. “My whole desire was to put together THE rock ‘n roll band for God. That’s what I wanted to do. I was so naïve to think that at that point in time – in 1976 – that I could just pick up where I left off and people were going to accept what I was doing, no matter what, because the music was good. I even had that conversation with David Geffen – ‘You’re not going to give me any of that Jesus music are you?’ I said: ‘David, I’ve got a good album here, I’ve got great guys working with me, and the songs are good.’ And so he let it go…”

Anxious to share his newfound faith, when Souther-Hillman-Furay broke up, Furay decided to go solo. “My whole desire was to put together THE rock ‘n roll band for God. That’s what I wanted to do. I was so naïve to think that at that point in time – in 1976 – that I could just pick up where I left off and people were going to accept what I was doing, no matter what, because the music was good. I even had that conversation with David Geffen – ‘You’re not going to give me any of that Jesus music are you?’ I said: ‘David, I’ve got a good album here, I’ve got great guys working with me, and the songs are good.’ And so he let it go…”

I’ve Got A Reason came out on Geffen’s Asylum label. The title track made it clear things had changed; “Music was my life, finally took everything/Ain’t it funny how you got it all and not a thing…”

“[Before] I wrote that song, I was so impassioned on being a rock ‘n roll star to the same degree that Stephen and Neil and Jimmy Messina and Timothy B. and Randy Meisner and all of those guys had become, that that was the only thing that was driving me. I was so driven, I couldn’t even see reality…And when Al led me to the Lord, it was like God opened up my eyes and showed me; ‘You think this is all that there is to life – your name written on lights at Carnegie Hall or at Madison Square Garden? Let me show you what’s real.’

“[Before] I wrote that song, I was so impassioned on being a rock ‘n roll star to the same degree that Stephen and Neil and Jimmy Messina and Timothy B. and Randy Meisner and all of those guys had become, that that was the only thing that was driving me. I was so driven, I couldn’t even see reality…And when Al led me to the Lord, it was like God opened up my eyes and showed me; ‘You think this is all that there is to life – your name written on lights at Carnegie Hall or at Madison Square Garden? Let me show you what’s real.’

“And all He had to do was to touch me in my family – with my wife – and man, it put everything in perspective. God knew where to touch me. Nothing mattered anymore, [except] ‘I want my wife and I want my family.’ And that really set me on a whole different course.”

“And all He had to do was to touch me in my family – with my wife – and man, it put everything in perspective. God knew where to touch me. Nothing mattered anymore, [except] ‘I want my wife and I want my family.’ And that really set me on a whole different course.”

The album was lambasted by critics – the very same Rolling Stone Record Guide that afforded Poco five stars gave I’ve Got A Reason a one star rating.

Two more albums for Asylum, Dance A Little Light in 1978 and I Still Have Dreams the following year toned down the message somewhat, and the latter even scored a hit, with the title track edging into the top 40 pop charts. But sales were slow, and he was eventually dropped from the label.

ORDAINED

In 1982 Furay released Seasons of Change, his first for a Christian label.

That same year he was ordained as a minister at a Calvary Chapel in Colorado.

That same year he was ordained as a minister at a Calvary Chapel in Colorado.

“I had no idea that this was where the Lord was going to lead me. I had no idea when I got saved that I was going to end up pastoring a church.”

After so many years defining himself as a musician, he’s aware of the dangers of getting too attached to any job, even running a church. “I don’t care if it’s rock ‘n roll or it’s the ministry – things can get in the way of your life. And as Paul said; if you can’t keep your family together, how in the world are you gonna take care of the Church of God? You’ve got to maintain. And that’s one of the things that I think the church has finally got and understands – at least here in Colorado with me – is that, though I am a pastor, and I do care about them as part of God’s family and flock, they know that my life goes beyond these walls, and sometimes I’m going to be here and sometimes they’re gonna have to adjust to the fact that someone else is going to be here for a day or two.”

POCO REUNION

Furay and the church went through considerable trials before coming to an understanding about his life beyond it’s walls.

In 1989 the original members of Poco reunited for Legacy. In a misguided attempt to sound up-to-date, outside writers and session players were brought in, destroying what made the band great. Ironically, the album garnered strong sales

They played shows promoting the album, and while on tour Furay learned that some members of his church had turned on him, insisting he quit the band. It was a tough time, and today he claims that “God’s grace” helped get him through: “Which is easier said than done. At first I was offended. I was a lot younger – a lot younger in the Ministry – and it was offensive that people did not understand. I had kept the congregation abreast of everything that was going on, and when I finally did confront the church I found out that it was only two or three people that were upset, and the other part of the church was in support. But our church is a small church, and anybody knows you throw a rock in a pond – a little pond – and the ripples are going to go out. So that’s basically what happened.

“It’s really interesting; two of the people have come and gone, and come back again over the years. They know there’s stability here. They know we’re stable, and they know we’re gonna be here. One of the guys was on my board, and you know, it was really ugly. And today – ten years later – he’s coming back; his life is pretty topsy-turvy right now. He’s gone through two marriages, and back then he wasn’t even married. But he’s just beginning to see that there were some things that we were saying way back then that he just didn’t get, he didn’t grasp, about total Ministry. Another guy came in to the church after being away for six years, and caught me on the way out one day and he just started crying and he said ‘You know Richie I was really wrong about what we did years ago.”

HALL OF FAME

In 1997 the Buffalo Springfield were inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame, and Furay saw his old cohorts in a different light. Especially Stills and Young.

In the years since the group broke up, Stills and Young had become legends.

“Their careers define them, there’s no doubt about it. I know when we tried to get a reunion together back in the 80s, we had to really come to grips with who each other was at the time.

“And I felt that getting together with Stephen and Neil, that these guys were so secure in who they were as musicians and the success that they had, that it would not affect them one way or the other; it didn’t matter to them.”

Instead, petty jealousy and insecurity – reminiscent of what had occurred during the band’s heyday – insured that a full-scale reunion would never happen.

“Now, my heart goes out to both of them – because they defined who they were by their careers. Again, I’m not gonna sit back here and judge or pre-judge somebody, but it would seem pretty obvious right now that there’s not much of a …walk with the Lord, as far as I can tell.”

When [Neil] had the brain aneurysm, from what I’ve read he had to go in and record a lot of that music on Prairie Wind – because he was actually afraid that he might not be here. Now what that meant to him, I don’t know. I don’t know if he believes in heaven and hell…The Bible tells us that there is a place like that.

“But with Neil, everybody was coming to me after that last album came out. He has a song [called] ‘When God Made Me,’ and they were asking ‘Has Neil become a Christian?’

“I’ve listened to this song and I don’t really hear anything in it at all that remotely suggests that that was the case of what happened. But you know, we continue to pray for him, I continue to…try to be a beacon. If anybody wants to talk to me, hey, I’m here.”

“When we got together and tried to do the reunion project, of course we had to go through the whole routine again of Neil making an entrance and coming in late and all, so were sitting around waiting on him and I hadn’t even see Stephen in probably five or six years.

“And as I’m standing there in the kitchen, he comes around down the hallway and [says] ‘Hey Richie, how are you? Good to see you man, ba da da da – I hear what you’re doing and it sounds like it’s really good; but you don’t believe in that rapture stuff, do you?’

“So what that did for me was open up an opportunity to share my faith straight up for the next 30 or 40 minutes waiting for Neil to come. And I had a captive audience, which was really pretty cool.

“After that Stephen came up to me the next day, and he said, ‘I want you to talk to my boy. I think you’d really do good, if you’d talk to my boy.’ And I said ‘Well Steve, what you mean?’ And he said ‘Well, just talk to him.’

“And as it turned out – I’m trying to remember which son it was – but he was a born again believer – and it was like, man, this is really too cool. And his mom came up to me and I think she got it.”

Al Perkins tells of the time he tried to share his faith with Stills – who told him he had spoken to his priest, and the priest had said he was okay.

Furay laughs. “Yeah – ‘I talked my priest and he told me I’m okay.’ Well, let me tell you what; there’s one mediator between man and God, and that’s the person of Jesus Christ.”

“I think Steve – as far as spiritually goes – I think he’s a ‘born in America’ Christian, if you know what I mean. I don’t know if his Catholicism really took ahold.

“Basically, I think he is one of those guys who maybe feels ‘Well, I’m living a good life, I don’t hurt anybody. I’m born in America. I grew up in the church.’ You know, some people look at [it like], if you grow up in a certain denominational church, you’re in.”

Twenty years ago, the band’s original rhythm section of Dewey Martin and Bruce Palmer toured together as Buffalo Springfield Revisited. I met Dewey, who made a point of identifying himself as a believer. “Dewey has made at least a profession of faith. I’m not around him, so I don’t really know how his walk is, but Dewey has told me the same thing, that he has accepted Christ, and Scripture says that the Lord knows those who are his, so I can only go at face value on what he says. Jesus said you’ll know them by their fruit. And again, I’m not around Dewey, so I don’t know exactly what kind of seeds he’s sowing, but I have to believe it, and if you had a conversation with him, then certainly something is going on there.“

And then there’s Bruce. In May ’67 he was deported back to Canada for drug possession, and while he returned intermittently, it was never the same. Alcohol and drug dependency brought his life to an end when he died of a heart attack in 2004. “At the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame induction I couldn’t hardly talk to Bruce.”

Palmer spoke directly before Furay, and was clearly upset that Neil had decided to boycott the event at the last minute, leaving the rest of the band in the somewhat familiar role of being one man short. Palmer gave a somewhat incoherent speech that managed to confuse the entire audience. “And as I look at it now, it wasn’t nearly as rambling as I thought when I was sitting there listening to it. But as we were sitting at dinner that night, he’d been drinking a little bit, and it was like, you know, ‘I can’t even talk to you.’ He wanted to engage in a serious conversation, and I couldn’t even talk to him. It was going nowhere. And I felt really sad, because I felt like I just left him hanging, and that was really my last conversation before he passed away a couple of years ago.”

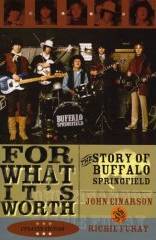

In conjunction with the Hall of Fame ceremonies, Furay and music historian John Einarson wrote For What It’s Worth: the Story of the Buffalo Springfield. An excellent chronicle of the band’s ups and downs, a revised edition is currently available.

In conjunction with the Hall of Fame ceremonies, Furay and music historian John Einarson wrote For What It’s Worth: the Story of the Buffalo Springfield. An excellent chronicle of the band’s ups and downs, a revised edition is currently available.

1997 was a busy year for Furay. In addition to the book and the Hall of Fame ceremony, he returned to the studio for the first time in years, releasing In My Father’s House, a first-rate collection of songs dealing with his faith. The disc was all but ignored, prompting the Encyclopedia of Contemporary Christian Music to describe Furay as going from ‘one of the most underappreciated performers in mainstream rock, to one of the most underappreciated performers in contemporary Christian music.’

1997 was a busy year for Furay. In addition to the book and the Hall of Fame ceremony, he returned to the studio for the first time in years, releasing In My Father’s House, a first-rate collection of songs dealing with his faith. The disc was all but ignored, prompting the Encyclopedia of Contemporary Christian Music to describe Furay as going from ‘one of the most underappreciated performers in mainstream rock, to one of the most underappreciated performers in contemporary Christian music.’

His outlook has changed considerably over the years.

“I think I’ve mellowed, and I’ve kind of scoped out the territory a little bit differently now. After making those first three albums, and getting less and less support from the record company, it was just kind of like ‘Okay, Lord, what would you have me do?’ and I set music aside for probably 10 years, 15 years, of just not really doing much at all. And it didn’t matter. It didn’t matter.

“When I started again, it took on a whole different perspective. It was no longer a career. And no longer was the ego so driven that I had to be recognized, or whatever. It just didn’t matter.”

“It was kind of humbling – I was right back to folk music. I went back to an acoustic guitar and just me. And then my worship leader and I started going out. He became my band for about ten years. Over the last year we’ve added a bass player and a drummer, and my daughter Jessie is singing with us, too. [We] evolved over ten years without really trying…it’s just an opportunity to go out and play music, music that I feel is good.”

NEW ALBUMS

After almost a decade between releases, Furay has two new CDs; Heartbeat of Love, which consists of mainstream-oriented material, and the faith-based I Am Sure.

After almost a decade between releases, Furay has two new CDs; Heartbeat of Love, which consists of mainstream-oriented material, and the faith-based I Am Sure.

Each features an impressive list of guests. Poco alumni Rusty Young and Timothy B.Schmit, Mark Volman, Al Perkins, Kenny Loggins and Stephen Stills all show up on Heartbeat of Love, his first secular release in over 25 years. Even Neil Young makes an appearance, singing and playing guitar on a remake of ‘Kind Woman,’ Furay’s voice has weathered the years extremely well, and forty years on, hearing him alongside Stills and Young it’s clear he’s still the best singer.

The packaging is exceptional. “Wait until you see it; Oh, my gosh. I guarantee, from an independent guy, you haven’t seen a package like this.” It’s not an idle boast; the disc is housed in a bound booklet with die-cut and embossed lettering more common on expensive limited edition titles.

I Am Sure boasts an equally noteworthy guest list, including three Poco vets; Jim Messina, Paul Cotton, and Rusty Young, three members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and Chris Hillman,

I Am Sure boasts an equally noteworthy guest list, including three Poco vets; Jim Messina, Paul Cotton, and Rusty Young, three members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and Chris Hillman,

Along with the new discs, Furay has begun to take on more high-profile shows.

“Last summer we went out and did a series of concerts – ten shows in 14 days. We did one show with America, four with Linda Ronstadt, and five churches. It was kind of neat for us, because when we were out there playing with Linda, it was a whole different set – obviously – with a lot of my history.”

He was surprised to get the call for the Ronstadt shows. “Because Linda…has publicly [stated] that it makes her uncomfortable to even know there’s born-again Christians or conservatives in her audience. So I was very surprised that I even got the opportunity to go out there and do the shows. But we did.”

Ronstadt’s management made it clear they wanted his more mainstream-friendly material.

“I hadn’t seen Linda [since] the seventies. When we finally did have our one encounter, it became a monologue from her – a filibuster. I didn’t even have a chance to say anything. It was ‘Oh Richie, how are you, it’s nice to see you, and oh boy, you and J.D. and this and that and the other, and ‘Oh, isn’t this country we live in just awful?’ And then she just went off for the next six or seven minutes before I could even get a chance to say anything; ’This is what I do, this is my show, and I’m in charge here.’ And then she said, ‘I have to go – I have to go on stage now.’ That was it. And I never really had another opportunity. Nor did I even want another opportunity. We just did our thing.”

He’s well aware of the one-dimensional reactionary Christian so often portrayed in the media; “I know, it’s kind of” – he starts to laugh – ‘Hmm – I don’t know that guy.’”

“It’s very frustrating. I want to think of myself as more of an independent thinker, but at the same time, I will probably embrace the more conservative issues.”

Other performers are far less concerned about the fact their opening act is a Pastor. “It’s real interesting. Like with America; it was totally different with them than it was with Linda. Gerry [Beckley] stood in the sidelines for our whole sound check and for our whole set, and he was just enamored by what we were doing. And we sang with them – they came here and played a couple of months ago and we went up and sang a song with them. But it didn’t seem to be an issue with them.

“What was really cool was that we did a show with America, and then we did two churches, and then we did two shows with Linda, and then another with a church. They were intermingled, where we could go and really get refreshed and built up ourselves, because my group has a whole two-hour show we can do in churches as well as out in the mainstream.

He’s very happy with his current position.

“I believe that the Lord has given me a unique opportunity. I’ve learned over the years that there is a balance to this – that you don’t go out and proselytize on a secular stage. Earlier on I really probably didn’t grasp that as well as I could have. But over the years I learned that it’s more about the love that you can show – there we are back word ‘love’ again – it’s the love that you can show that’s going to attract people to you.

“The church today, my particular fellowship, has become so supportive. They know what I’m doing out there, and they know that the ministry goes beyond the four walls of this church. I get an opportunity to play my old music and I’ll tell you what – lots of times I have more of an opportunity to share my faith when I’m singing songs about my wife than when I’m singing ‘In My Father’s House.’ it’s just amazing how it works. But you know what? It just doesn’t even bother me. It’s not even an issue with me anymore – it’s just not an issue. I’m as comfortable playing at Humphries in San Diego, as I am playing at Harvest Christian Fellowship in Riverside, California. It doesn’t make any difference.”

“The church today, my particular fellowship, has become so supportive. They know what I’m doing out there, and they know that the ministry goes beyond the four walls of this church. I get an opportunity to play my old music and I’ll tell you what – lots of times I have more of an opportunity to share my faith when I’m singing songs about my wife than when I’m singing ‘In My Father’s House.’ it’s just amazing how it works. But you know what? It just doesn’t even bother me. It’s not even an issue with me anymore – it’s just not an issue. I’m as comfortable playing at Humphries in San Diego, as I am playing at Harvest Christian Fellowship in Riverside, California. It doesn’t make any difference.”

As Furay looks back, there’s much to celebrate. Next month he and Nancy will celebrate their 40th wedding anniversary. In addition to their four daughters, they recently celebrated the birth of their fifth grandchild.

And he’s busier than ever.

“It’s kind of neat, you know, the Lord has given me two books; a secular book [For What It’s Worth] and a testimony book [Pickin’ Up the Pieces], He’s given me basically four CDs right now; one mainstream [The Heartbeat of Love] – which I haven’t done in 25 years – then I’ve got In My Father’s House, Seasons Of Change [reissued in 2004] and I Am Sure as far as worship. So I’m a little package here that’s just ready to go. And the only thing I do…” He begins to laugh… “is say ‘Lord, why at sixty-two?’

© John Cody 2007