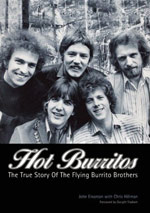

• Hot Burritos: The True Story of the Flying Burrito Brothers, by John Einarson with Chris Hillman

Music history is full of myths. Rock music sucked between the time Elvis went into the army and the Beatles’ arrival. Robert Johnson achieved his talent by selling his soul to the devil. Gram Parsons invented country-rock.

While most are laughable or harmless, the latter is – surprisingly – taken as fact in spite of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

As the original vocalist for The Flying Burrito Brothers, Parsons, who died in 1973, gained notoriety for all the wrong reasons. His drug overdose at 26 years old insured rock immortality; he lived fast and died young.

As the original vocalist for The Flying Burrito Brothers, Parsons, who died in 1973, gained notoriety for all the wrong reasons. His drug overdose at 26 years old insured rock immortality; he lived fast and died young.

The Burritos helped lay the foundation for a genre that would reach critical mass long after they had gone. A commercial non-starter, others, most notably the Eagles, tweaked the formula and made millions. These days, alt country acts regularly cite the Burritos as a primary influence, many crediting Parsons as single-handedly creating the genre.

The only problem – it was a band, not a solo venture. Parsons’ fellow players are continually given short shrift.

As Burritos guitarist Bernie Leadon explains; “How can you compete with a dead guy? You just can’t. It’s a martyr thing. Gram fell on his sword so he’s a dead hero. He’s mythic.”

In John Einarson’s Hot Burritos: The True Story of the Flying Burrito Brothers the balance is corrected.

In John Einarson’s Hot Burritos: The True Story of the Flying Burrito Brothers the balance is corrected.

Einarson dug deep to get to the truth, interviewing the requisite band members, but also record company personal, producers, and management, some going on record for the very first time.

“I wanted to make sure it wasn’t just the musicians that I interviewed,” he notes. “The people that were in and around A & M Records at the time add a whole other dimension to the story, and in many ways corroborate what some of the musicians are saying, but they also add a lot of color to the story as well.”

The collective voice speaks volumes, depicting a reality wildly at odds with commonly held conceptions.

Significantly, Einarson – who has a well-deserved reputation as one of the finest chroniclers of the West Coast music scene – was able to enlist Chris Hillman’s full cooperation. Despite being co-creator and undisputed leader of the group, Hillman is rarely given proper credit for his contributions. As a founding member of the Byrds, Hillman’s name alone guaranteed the Burritos would be signed sight unseen.

Until now, he has refrained from speaking at length about the band. “Coming into this project, he was a little frustrated at recent events in the whole Parsons mythology/legend kind of thing.”

For instance, the billing on a recent Burritos CD; Gram Parsons Archives Volume One: Gram Parsons with the Flying Burrito Bros Live at the Avalon Ballroom 1969. “Gram’s name is splashed all over the place, and Chris is like a footnote in it.”

Two recent books reinforced the idea of Parsons as sole creative force. “He’s a little stung by the reference to him being the ‘bitter lieutenant’ in David Meyer’s book (Twenty Thousand Roads: The Ballad of Gram Parsons and His Cosmic American Music. And he also didn’t like the book that [Gram’s daughter] Polly Parsons authorized by Jessica Hundley (Grievous Angel: An Intimate Biography of Gram Parsons).

“All of this stuff just kind of built up with him, and he said ‘You know, it’s time; it’s time to really focus on telling the real, true story of the Burritos. They weren’t a foot note – they were a band. They were not just Gram Parsons’ backing band. We were a band of 4 or 5 guys, and we all contributed to this thing called the Flying Burrito Brothers. And we’re getting lost in the mists of time, as the legend of Parsons grows and grows and grows.’”

Parsons certainly did much that was right, and for a season, he was inspired.

It was his idea, for instance, to bring an R & B edge to the band, with covers of ‘Dark End Of the Street’ and ‘Do Right Woman’ fitting perfectly with the southern gothic style.

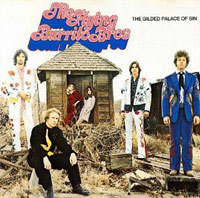

Parsons’ description of the Burritos; “…a Southern soul group playing country and gospel-oriented music with a steel guitar,” was right on the money. Gospel informed everything from album titles (Gilded Palace of Sin), to Hillman/Parsons originals like ‘Sin City’ and ‘Down in the Churchyard,’ covers of ‘Farther Along’ and ‘I Shall Be Released’ and Parsons’ flamboyant stage outfit, featuring a large cross embroidered across the back of his jacket.

Parsons’ description of the Burritos; “…a Southern soul group playing country and gospel-oriented music with a steel guitar,” was right on the money. Gospel informed everything from album titles (Gilded Palace of Sin), to Hillman/Parsons originals like ‘Sin City’ and ‘Down in the Churchyard,’ covers of ‘Farther Along’ and ‘I Shall Be Released’ and Parsons’ flamboyant stage outfit, featuring a large cross embroidered across the back of his jacket.

Steel guitarist Al Perkins – who joined the Burritos in 1971 – produced many early Contemporary Christian recordings. Hillman – today a member of the Greek Orthodox Church – credits Perkins’ influence as integral to his own eventual acceptance of Christianity.

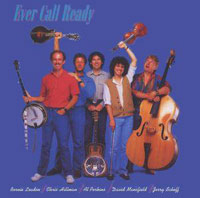

In the 80s, Perkins, Hillman and Leadon recorded a pair of bluegrass gospel efforts, Ever Call Ready and Down Home Praise that made their intentions clear; “fellow Christian musicians having a desire to express their love and appreciation for Christ’s work in their lives.”

In the 80s, Perkins, Hillman and Leadon recorded a pair of bluegrass gospel efforts, Ever Call Ready and Down Home Praise that made their intentions clear; “fellow Christian musicians having a desire to express their love and appreciation for Christ’s work in their lives.”

The Burritos – as Hillman maintains – were first and foremost a band. Surprisingly, the focal point onstage was neither Hillman nor Parsons. “When you went to see the Burritos, [steel guitarist] Sneaky Pete was the star of the band,” claims Einarson. “He didn’t look like a star – he didn’t stand up front or anything – but musically, he was the star. His playing on that first album is just astounding. The sole lead instrument and the things he does with it are just amazing.”

Like his playing, the instrument itself was decidedly unorthodox. “He approached the thing from such a unique and individual perspective – the tuning, the gadgets – everything about it. It was an old, old steel, and it didn’t have the same kind of pedals as other steels, yet he was able to make magic with it.”

Like his playing, the instrument itself was decidedly unorthodox. “He approached the thing from such a unique and individual perspective – the tuning, the gadgets – everything about it. It was an old, old steel, and it didn’t have the same kind of pedals as other steels, yet he was able to make magic with it.”

Kleinow, a dedicated family man, had little interest in socializing. In spite of the era, he abstained from drugs (Perkins, his replacement, was like-minded; a teetotaller who never so much as sampled a drink or drug).

Living in Hollywood, Kleinow was able to keep his day job as an animator, working on children’s classics like Gumby and Davey & Goliath, a series produced by the Lutheran Church.

“Everybody deferred to Pete. They had such a deep and abiding respect for him; they wouldn’t argue, they wouldn’t fight with Pete.”

Former Byrds drummer Michael Clark – whom Einarson considers the ‘forgotten Burrito’ – came in shortly after the debut album was recorded. “It’s amazing, all that Michael did, when you consider he didn’t really have a lot of talent as a drummer. Musically, he was always the weakest link in the band. But on the other hand, in terms of audience appeal, back in ’65, in ’66, Michael was the guy. He had an attractive appeal – certainly, to the girls – to the teenyboppers.

“He was a kind of guy that everybody liked having around. And you put up with his musical deficiencies, because you liked having him around, until the point that his drinking became too much for most people to bear.”

That happened on quite a few occasions, “It happened in the Burritos, too. Hillman told me that they actually considered hiring Don Henley at one point, after Shiloh [Henley’s band with Al Perkins] folded. Al was in the Burritos, and Michael’s drinking was becoming such a problem, that they actually considered asking Henley. You can sort of extrapolate how the musical landscape of rock would have changed, perhaps, had Henley gone into the Burritos, and not met Glen Frey; all sorts of things might have happened.”

In spite of his technical deficiencies, Clark, who would eventually succumb to cirrhosis of the liver in 1993, remained with the Burritos until the end, subsequently forming Firefall with Parsons’ replacement, Rick Roberts.

“If you look at all the books on Gram, he’s barely mentioned. In 20,000 Roads, you’re hard-pressed to find his name in there anywhere. When I would bring him up, for a lot of people, it was the same kind of thing; ‘He was just the drummer. He was a good-time guy. He was a party guy.’ And that’s really it; he’s the forgotten Burrito. And yet, next to Chris, he was in there the longest.”

As important as the rest of the players were, it’s the dynamic between Hillman and Parsons that forms the heart of the story. “It’s a fascinating relationship,” Einarson agrees, “and I tried to look beyond just the musical attraction between them. There was something deeper, something more intrinsic that brought them both together.

“The books that feed the Parsons mythology to death never really look at that. They give short shrift to Hillman and the relationship, without realizing what drew those two together, and what forces then eventually blew them apart.”

Parsons grew up in a wealthy Florida family, his life impacted by suicide and alcoholism. It was a legacy he chose to keep private. “I don’t think a lot of people at the time were aware of his background as much as they are now. Even Chris – he got bits and pieces of it over the years.

“There are people who say that given what Gram came through, he should be excused for what he did. But Hillman disagrees with that. As he says, he went through a horrible situation in his family, too. [Hillman’s own father committed suicide, triggering an emotional and financial catastrophe for the family], and he didn’t use that as his excuse to be abusive and irresponsible. He moved on; he got over it. He didn’t dwell on it. And as Hillman says, maybe if Gram had been able to do that, things might have turned out differently.”

For the most part, Einarson sticks to the Burritos era. “I purposely didn’t go deep into the really early years, because Meyers did that really well in 20,000 Roads. I actually thought the strength of that book was in the really early years and the family, and the dysfunctional family part of the book.”

Like Meyers, he believes Parsons’ upbringing impacted much of what came later. “The thing you’ve got to consider is that Gram came from tremendous wealth – he had everything on a silver spoon. The whole notion that his parents bought him a nightclub to perform in as a teenager – I mean, that’s just unbelievable. That’s not what everybody else went through. So, on the one hand you could say, certainly he came from a terrible situation, a terrible family; a dysfunctional family. But on the other hand, he came from such incredible indulgence and wealth, having everything you could possibly want.”

Like Meyers, he believes Parsons’ upbringing impacted much of what came later. “The thing you’ve got to consider is that Gram came from tremendous wealth – he had everything on a silver spoon. The whole notion that his parents bought him a nightclub to perform in as a teenager – I mean, that’s just unbelievable. That’s not what everybody else went through. So, on the one hand you could say, certainly he came from a terrible situation, a terrible family; a dysfunctional family. But on the other hand, he came from such incredible indulgence and wealth, having everything you could possibly want.”

Leaving was a habit. He quit the International Submarine Band before their debut album was even released, and was with the Byrds barely five months – Hillman had brought him in for 1968’s Sweetheart of the Rodeo – before exiting without notice on the day they were to depart for a tour of South African.

He managed to stay with the Burritos slightly longer, but by the end his role was severely diminished. From co-creating the band with Hillman to his firing took just over a year.

“They were only a creative force for about six months. Even though Gram was in the band longer, he kind of had shot his wad at that point, and they weren’t getting along. It’s that first six months when they were together – that music still defines the two of them. When you think of Gram Parsons, you think of the songs on Gilded Palace of Sin, or even on Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which was with Hillman. And Hillman too; some of the best stuff he’s ever written was on that first Burritos album.”

For Parsons, the notion of being a team player just wasn’t in the cards. He turned what could have been an historic bridging between two distinct cultures – a Byrds appearance at Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry – into a disaster by manipulating the program to feature his own material.

For Parsons, the notion of being a team player just wasn’t in the cards. He turned what could have been an historic bridging between two distinct cultures – a Byrds appearance at Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry – into a disaster by manipulating the program to feature his own material.

Once the Burritos were up and running, he sabotaged an important showcase gig for A&M Records by arriving too stoned to perform properly. “Right out of the shoot; the band just got started, and already, they’re heading downhill.”

At the time, such irresponsible incidents may have seemed reckless, yet somehow true to the rock ‘n’ roll spirit. “Certainly,” Einarson notes, “with age comes a little more wisdom. At the time, you just looked at it as an incident; it just happened. In hindsight, I think Chris was able to see the bigger picture. To put it all into perspective, and understand what it was that motivated Gram to do those things. The unfortunate thing is he died so young, so you have only a limited number of years to put his life in perspective. But when you see the bigger picture, you’re able to connect the dots, and put it all together.

For Hillman, working on the book meant revisiting memories positive and painful. “He said it was very cathartic. We spent three very intense days reliving all of this stuff, and every night he would be up late, or he’d wake up, and be having a lot of these thoughts churning around that he hadn’t thought of. We’d meet the next day, and hash it out.

“You get that sense; that he’s trying to really open up and bare his soul on a lot of this stuff, to get a lot off of his chest that he’s held inside for a very long time. It’s not like this festered with him, or in any way coloured or influenced his career, but he put it aside for a long time, and now, as he said in the book, when you’re forced to relive it and rethink it, you get more of a perspective on it.”

Despite the forthright, at times brusque, manner, Hillman didn’t request any changes in the final manuscript. “He said he was very proud of it, and had no problem with the tone. He felt it was very honest, it was very forthright, and it was, as he said, the true story of the band.”

The Burritos held enormous promise, which was to a large extent squandered. Hillman pulls no punches; but, as Einarson notes, the anger is directed as much at himself, realizing, had he been more assertive, “things would have been different. Gram might have been sitting down talking to us today.

“Certainly, he feels frustrated; he feels a sense of helplessness as to what happened. Even though he realizes no one could help, no one could have saved Parsons, he’s looking back on a lot of events in the Burritos, saying; “If only I had been a stronger leader. If only I had stepped up to the plate. If only this and that. But he wasn’t ready yet. He wasn’t mature enough to really take the reins. If there’s any bitterness, it’s his own frustration.”

Hot Burritos is Einarson’s third consecutive book exploring the Southern California music scene of the 60s and 70s. Desperados: The Roots Of Country Rock (2001) and Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of The Byrds’ Gene Clark (2005) are well worth seeking out for anyone interested in learning more about the vibrant music of the era.

He’s currently working on two biographies; Arthur Lee and Love continues the L.A. connection, while the first-ever biography on Canadian folk legends Ian & Sylvia promises a fresh perspective on the transition from folk to country rock.

Legend: The Story of Poco, by Jerry Fuentes, Groundhog Press

Legend: The Story of Poco, by Jerry Fuentes, Groundhog Press

The Flying Burrito Brothers were hardly alone when it came to mixing country and rock music.

For industry insiders – and those who witnessed their early concerts – the act predicted to finally take the sound nationwide was Poco.

Starting from the ashes of Buffalo Springfield, Richie Furay and Jim Messina put together a quintet far tighter and professional than the competition, of which there was plenty; individually and collectively, the Byrds attempted various ventures to generally less-than enthusiastic audience response, while Hearts and Flowers, the Dillards, The Stone Poneys – even established stars like former Kingston Trio front man John Stewart and Rick Nelson were performing their own country-rock hybrids.

But Poco were the band picked to click. For a variety of reasons, they never broke through on any substantial scale.

Poco expert Jerry Fuentes covers every period of the band, who are still on the road more than 40 years after their debut. It’s a well told, albeit frustrating tale of revolving personnel, missed opportunities and ill-advised artistic decisions. Ironically, about the only thing they were spared was a drug problem.

Essential reading for Poconuts.

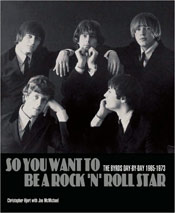

So You Want To Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star: the Byrds Day By Day 1965-1973, by Christopher Hjort, Jawbone

So You Want To Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star: the Byrds Day By Day 1965-1973, by Christopher Hjort, Jawbone

It’s not the kind of book one would sit down and read cover to cover, but for Byrds aficionados, So You Want To Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star is a treasure trove of reference material.

Assembled from newspapers, eye witness reports, fan magazines and more, the information and detail contained is absolutely unique, concentrating on areas generally glossed over in traditional biographies.

Period reviews and just-the-facts reporting present incidents as they occurred – or were perceived at that time – rather than reinterpreted and placed in historical perspective. For instance, the underwhelming response to Sweetheart Of The Rodeo shows just how far country rock had to come – the New York Times described it as “probably the most insulting album of the year.”

Hjort has used this format before, with the equally enjoyable Strange Brew: Eric Clapton and the British Blues Boom 1965-1970. Relying on a multitude of sources pretty much guarantees there will be errors, usually dates and venues, but that goes with the territory.

A welcome addition to the Byrds’ bookshelf.

© John Cody 2009