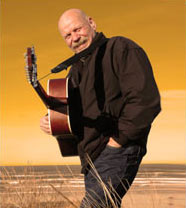

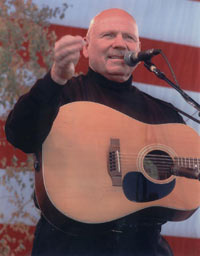

Barry McGuire has gone through some serious career changes over the last half century.

He first gained fame in the early 1960s, as the star of the New Christy Minstrels, a squeaky-clean folk group wholesome enough to perform at the Kennedy White House.

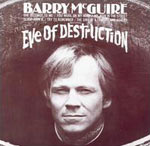

By the middle of the decade, he was an angry, folk/rocking protest singer, warning that we were on the ‘Eve of Destruction.’ Movie roles followed, along with a stint on Broadway singing and shedding his clothes in the boundary-shattering musical Hair.

Jump forward to the 1970s, and – after a few years lost in a drug haze – McGuire was singing a new tune; songs of faith, and once again safe enough to return to the White House.

Jump forward to the 1970s, and – after a few years lost in a drug haze – McGuire was singing a new tune; songs of faith, and once again safe enough to return to the White House.

At 72, he hasn’t slowed down a bit; an amalgamation of all that came before, he’s passionate, opinionated, and willing to challenge the status quo no matter what the cost. We spoke as he was preparing to embark on a world tour.

It’s an almost forgotten chapter of music history. In the years between Elvis joining the Army and the Beatles’ arrival in America – roughly 1958-1964 – folk music swept the nation. Acts like the Kingston Trio, the Brothers Four and the Chad Mitchell Trio scored hit after hit.

The New Christy Minstrels were right up there with the best of them. Their squeaky-clean image and lighthearted fare like ‘Silly Ol’ Summertime’ and ‘Chim Chim Cheree’ was perfect for the post-McCarthy era. Regular TV appearances and constant touring assured the act an extraordinary level of popularity.

With a revolving cast of ten singers, the Los Angeles-based troupe boasted a wealth of talent; Gene Clark, Kenny Rogers, Kim Carnes, Larry Ramos [The Association] and Jerry Yester [Lovin’ Spoonful] all came through the ranks. McGuire, who co-wrote their biggest hit, 1963’s ‘Green, Green,’ was by far the most popular member.

With a revolving cast of ten singers, the Los Angeles-based troupe boasted a wealth of talent; Gene Clark, Kenny Rogers, Kim Carnes, Larry Ramos [The Association] and Jerry Yester [Lovin’ Spoonful] all came through the ranks. McGuire, who co-wrote their biggest hit, 1963’s ‘Green, Green,’ was by far the most popular member.

During his time with the Minstrels, McGuire discovered psychedelic drugs. Along with fellow Christy Paul Potash, the two became enthusiastic converts.

“We’d smoke marijuana, and we’d say ‘What are we? Where do we come from?’ The hallucinogenic drugs were kind of like a sacrament to open the door to a greater awareness of reality. It would break down barriers; all of a sudden everything became equal. A fly, a planet, a person, a tree, a rock, a star – everything was connected.”

He believes it was an era in which God used drugs to bring people closer to Him. “I think it was, and I think it still is. But we didn’t have any foundation for what we were discovering.”

In addition to drugs, there were other, equally potent changes taking place. The British Invasion had decimated the folk scene almost overnight – the Minstrels’ final top 40 showing was released in April 1964, just as the Beatles were taking over – yet not all the folkies were concerned. “I loved the music; I just loved it,” McGuire recalls.

In addition to drugs, there were other, equally potent changes taking place. The British Invasion had decimated the folk scene almost overnight – the Minstrels’ final top 40 showing was released in April 1964, just as the Beatles were taking over – yet not all the folkies were concerned. “I loved the music; I just loved it,” McGuire recalls.

Roger McGuinn – who had worked as an accompanist with the Limeliters and the Chad Mitchell Trio – shared his enthusiasm; “Roger was way ahead of the curve. He loved their music. They influenced him when he put the Byrds together.” McGuinn combined folk and rock and hit number one first time out with ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’

McGuire knew or would eventually work with all five of the original Byrds. “I knew Roger when he worked with the Chad Mitchell Trio, and we brought Gene Clark out from Kansas City in the Minstrels. And David Crosby;” he laughs, “he couldn’t get in the Minstrels. I think [leader] Randy [Sparks] didn’t really – they didn’t get along that well together.” The Byrd’s rhythm section, Chris Hillman and Michael Clark would both appear on his 1970 LP, Barry McGuire and the Doctor.

In addition to the West Coast contingent, McGuire was close with many in the East Coast folk community, including John Sebastian and Zal Yanovsky [Lovin’ Spoonful], Denny Doherty and Cass Elliot [The Mamas & The Papas], and Tim Hardin. “I met John when he was in the Even Dozen Jug Band. We were doing a show at a University in New York, and they were on the bill with us. In fact, Cass was there with The Big Three, and Tim Hardin was there, too. I met them all at the same time.”

They bonded immediately. “We started getting together and hanging down in the Village. It’s a wonder we didn’t all get thrown in jail. One time I was at Denny’s apartment at the Hotel Earl, and we had probably a half a kilo of marijuana broken open on the table. In fact, we turned the table upside down, because we didn’t want it to fall off onto the floor. So we were all rolling joints and smoking, and Sebastian shows up, and he has a Rickenbacker 12-String. Zally said ‘Oh! Let me see it!’ and started playing it, and he was blastin.’ It’s like 3 or 4’oclock in the morning, and there’s a half a kilo of grass on the floor, and I’m thinking ‘We’re all going to jail, man.’

“It was summer, and it was hot, so the window’s open – it was the first floor. I just threw my legs over the window sill and dropped off on the sidewalk and; [whistles] ‘Taxi!’ I just left them there, man. But,” he still marvels, “they didn’t get busted.”

Inspired by changes internal and external, McGuire quit the Minstrels in January, 1965. The group’s management were not happy, and even threatened him with the old ‘You’ll never work in this business again.’ For a while, that seemed to be the case; he was informally blacklisted, and in spite of his recent success, couldn’t find work.

That didn’t stop him from hanging out. When the Byrds debuted at Ciro’s in early ‘65, he showed up to cheer his old cohorts on. McGuire didn’t sing a note that night, but he still managed to score a record deal.

By dancing.

Bear in mind, nobody danced quite like Barry. His presence on or off stage could light up a room, and that’s exactly what happened that night.

Lou Adler, a major player via his work with Jan & Dean and Sam Cooke, was in the audience, sitting with Bob Dylan. Mesmerized by Barry’s charisma, he decided he wanted him for Dunhill Records, his brand new label.

Things moved fast. A week earlier, Adler had given one of his staff songwriters, P.F. Sloan, a copy of Dylan’s brand new album Bringing It All Back Home for inspiration. Sloan – a brilliant, prolific writer still in his teens – had already delivered an album’s worth of tunes, including ‘Eve Of Destruction.’

The song’s doomsday scenario was perfect for the times; “You’re old enough to kill, but not for votin’/you don’t believe in war, but what’s that gun you’re totin’/and even the Jordan River has bodies floatin’/but you tell me over and over and over again, my friend/You don’t believe we’re on the Eve of Destruction.”

It was simply a matter for finding the right artist.

The Turtles had already been approached, as the band’s vocalist, Mark Volman recalls; “Phil Sloan had been sent over to present us a song to follow-up [Turtles’ debut hit] ‘It Ain’t Me, Babe.’

“Phil brought us ‘Eve of Destruction.’ He played it that afternoon at a rehearsal, and we said ‘No’ to it. It was much too strong lyrically for what we felt we could sing and actually pull off. I mean, we were just kids out of high school. We had just had a really nice kind of love song with ‘It Ain’t Me, Babe,’ and – even though we liked the song, and would record it for our first album – we felt ‘Eve…’ was not something we wanted to represent us as a single.

“When we told him that, he said ‘I have another song that might work better,’ and he played us ‘Let Me Be’ at the same sit-down. We chose that as our single, because we liked the message in ‘Let Me Be’ for us better that we liked the message of ‘Eve of Destruction.’”

McGuire had the world experience to sell the song, yet it wasn’t his first choice, either. Instead, it was a last minute addition to a three-hour recording session. With two songs completed and just a few minutes left, there was only time for one take. He read from a crumpled piece of paper containing the lyric, flubbing a line at one point. But it had the magic.

It quickly rose to #1, ousting the Beatles’ ‘Help!’ out of the peak position, and keeping Dylan’s ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ from achieving the same.

It quickly rose to #1, ousting the Beatles’ ‘Help!’ out of the peak position, and keeping Dylan’s ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ from achieving the same.

Both acts took note; in D.A. Pennebaker’s Dylan documentary Eat The Document, John Lennon and Bob are seen discussing McGuire. “I saw a video they did years ago in the back of a limousine. They were talking about Mama Cass, and my name came up.” At one point, Dylan attempts to get Lennon to sing about McGuire.

Dylan – the ultimate folk/rocker – was a passing acquaintance. “I didn’t know him really well. I probably met him maybe half a dozen times at the most. We didn’t talk that much about material. He thought I should sing a song in Spanish,” McGuire laughs, “he thought that would be cool.”

The song has never gone away. In addition to numerous reissues, it’s been covered by a wide variety of acts, including Jan & Dean, Hot Tuna, The Pogues, Cher, D.O.A., Glen Campbell, Pretty Things, Johnny Thunders, Paul Revere & the Raiders and Tiny Tim.

It certainly polarized listeners; some stations went so far as to ban the song, instead, playing ‘The Dawn of Correction’ a right-wing retort by The Spokesmen that became a top 40 hit itself.

Despite frequently topping ‘greatest protest song’ lists, McGuire disagrees with the label. “It wasn’t a protest song, it was just a diagnostic. If you go to a doctor and he says ‘You have a melanoma here, it looks like it’s malignant,’ you don’t call him a protest doctor. He’s just diagnosing your condition.”

Volman says the Turtles saw the potential downside in releasing the song – a guaranteed hit – as a single; “Even though ‘Eve of Destruction’ would go on and become a bigger hit, given the choice I would still take ‘Let Me Be.’” There was something about the song – sincere or contrived, it was easily lampooned; “It was a novelty record, basically. Anytime you get stuck with a record like that, you are never going to really compete with it again.”

Volman says the Turtles saw the potential downside in releasing the song – a guaranteed hit – as a single; “Even though ‘Eve of Destruction’ would go on and become a bigger hit, given the choice I would still take ‘Let Me Be.’” There was something about the song – sincere or contrived, it was easily lampooned; “It was a novelty record, basically. Anytime you get stuck with a record like that, you are never going to really compete with it again.”

McGuire’s follow-up single and album barely charted. Coming off such a huge hit, success should have been assured. It’s been suggested that the subsequent failure was down to retaliation – payback for what the powers that be felt was simply too radical a lyric for the teen audience.

Old pals The Mamas & The Papas sang background on a number of the album’s tracks, including their own ‘California Dreamin.’ Their version of the song – the group’s first hit – is the very same recording, with Barry’s vocal replaced by Denny, and a flute solo added.

Old pals The Mamas & The Papas sang background on a number of the album’s tracks, including their own ‘California Dreamin.’ Their version of the song – the group’s first hit – is the very same recording, with Barry’s vocal replaced by Denny, and a flute solo added.

A third and final Dunhill album, 1968’s The World’s Last Private Citizen, was released without much fanfare – or preparation; “It was just a bunch of outtakes. I was out of town and they just took a lot of takes that never got out – old takes – and put it together.”

Ironically, the disc showed far more variety than earlier efforts, and is the stronger album for it. There are a number of strong performances, including a pair of McGuire/Paul Potash originals; ‘Inner Manipulations,’ featured in The President’s Analyst, his feature film acting debut from the year before, and ‘Secret Saucer Man’ a close cousin to the Byrds’ ‘Mr. Spaceman.’

Ironically, the disc showed far more variety than earlier efforts, and is the stronger album for it. There are a number of strong performances, including a pair of McGuire/Paul Potash originals; ‘Inner Manipulations,’ featured in The President’s Analyst, his feature film acting debut from the year before, and ‘Secret Saucer Man’ a close cousin to the Byrds’ ‘Mr. Spaceman.’

McGuire relocated to New York City in 1969 for a featured role in Hair. Billed as ‘The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical,’ the production rewrote the rules for Broadway musicals, tackling until-then hidden subjects, and included a notorious finale in which the entire cast shed their clothing.

It was the perfect environment for his ongoing spiritual exploration. Often – especially during that particular era – the musical and spiritual were closely connected. “Well that’s where it all comes from, for me. If a song doesn’t have spiritual content – not blatantly scriptural like scripture and verse – but the reality of life,” then he’s not interested. “I mean, Hair – to me – was a spiritual statement.

“When I was doing Hair, I had a little poster that somebody had given me that said ‘God Bless God’ on my mirror. I thought a lot about the source – not about Christ – but about the source of all things, the creator. And for me, it was spiritual.

“When I was doing Hair, I had a little poster that somebody had given me that said ‘God Bless God’ on my mirror. I thought a lot about the source – not about Christ – but about the source of all things, the creator. And for me, it was spiritual.

“I remember talking with Jerry Ragni, one of the co-writers of Hair at the time. We were talking about how Hair was just a statement for us; a statement that we were all spiritual beings inhabiting these biological wetsuits. And the only reason we were here was to experience linear reality, because the only way non-linear beings can experience linear reality, is to hitch-hike a ride inside a linear host. That was the journey that I was on; I was looking.”

He returned to the coast in 1970. “I came back to California, and I was living with Denny Doherty. He had a house up on Appian Way, and I just went by his house one afternoon, and I stayed a year and a half.”

It was a dark period for both men. The Mamas & The Papas had broken up (their final top 10 hit, ‘Creeque Alley,’ [“McGuinn and McGuire just a getting’ higher/in L.A. you know where that’s at”] playfully name-checked Roger and Barry as the first of the folkies to hit gold), and Doherty had begun a solo career. Despite a classic radio-friendly voice that sold million for the group, his own records failed to catch on.

Drugs were no longer providing the inspiration and insight they once had, but that didn’t mean he was going to stop. “We were drinking and doing a lot of drugs. We weren’t doing any music at all. It was just drugs and conversations. People would come by.”

People like Jimi Hendrix. “He walked in one day, opened his guitar case, sat down and played the same lick for three days, in every position on the fret board. Denny was sharpening a knife, I was watching TV, and we were all smoking marijuana and drinking Crown Royal.

“After three days, Hendrix says; ‘Well, I got that lick,’ and put his guitar away and left.” The Age of Aquarius may have dawned, but what Hendrix left behind more closely resembled a Cheech and Chong skit. “Denny’s knife looked like a little fish knife; you could shave with it. He was slathered in black whetstone, his hands and his pants were covered. And so we went to bed for a couple of days and slept. That was a typical weekend. But that went on for a year and a half. Day after day after day.”

“After three days, Hendrix says; ‘Well, I got that lick,’ and put his guitar away and left.” The Age of Aquarius may have dawned, but what Hendrix left behind more closely resembled a Cheech and Chong skit. “Denny’s knife looked like a little fish knife; you could shave with it. He was slathered in black whetstone, his hands and his pants were covered. And so we went to bed for a couple of days and slept. That was a typical weekend. But that went on for a year and a half. Day after day after day.”

The search for truth had been abandoned. “I’d reached a point where I’d really given up. I didn’t think there was anything to be found. I thought that we were just naked apes; that we came up out of the ooze and the mud. That there was nothing to be found.”

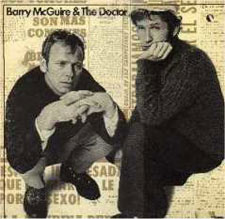

He signed with Ode/A&M Records, Adler’s latest venture. The resulting album, Barry McGuire & the Doctor was nothing like his earlier efforts. This time, there was more of a country/rock flavor, and a couple of tracks included the Flying Burrito Brothers; “They just came by” he recalls. “It was more of a jam session than anything else.”

It was loose – relaxed enough that today, Burritos bassist Chris Hillman can’t even remember the sessions. Guitarist Bernie Leadon, on the other hand, has vivid recollections. As Leadon recalled in John Einarson’s upcoming Hot Burritos: The True Story of The Flying Burrito Brothers; “We were on A&M Records, and Barry was signed by them also. Eric Hord was ‘the Doctor’ – a reference to his playing ability. Eric did one track using my only acoustic guitar [Leadon played electric], a 1966 Martin D-35, Brazilian rosewood. He had a cigarette hanging from his mouth during the take, and I was sitting across from him, watching the ash get longer and longer, and then fall on the side of my guitar. We finished the take, and he brushed off the ash. It had burned small holes in the white plastic binding material, which was the first real damage the guitar had endured.”

It was loose – relaxed enough that today, Burritos bassist Chris Hillman can’t even remember the sessions. Guitarist Bernie Leadon, on the other hand, has vivid recollections. As Leadon recalled in John Einarson’s upcoming Hot Burritos: The True Story of The Flying Burrito Brothers; “We were on A&M Records, and Barry was signed by them also. Eric Hord was ‘the Doctor’ – a reference to his playing ability. Eric did one track using my only acoustic guitar [Leadon played electric], a 1966 Martin D-35, Brazilian rosewood. He had a cigarette hanging from his mouth during the take, and I was sitting across from him, watching the ash get longer and longer, and then fall on the side of my guitar. We finished the take, and he brushed off the ash. It had burned small holes in the white plastic binding material, which was the first real damage the guitar had endured.”

Hord apologized, but the damage was done. Leadon kept the instrument. “Still have the guitar, still has the dings. Same guitar I used on all early Eagles records. Haven’t seen McGuire in 30 years – heard he became a born again preacher – probably good at it.”

The road to what Leadon describes as born again preacher came soon after they recorded together. During a show at the Whiskey a Go Go in October 1970, McGuire had an encounter that would prove portentous.

“I was working with Eric, and one night I walked out of the front door of the Whiskey and there’s this guy sitting there on a cross that’s about 8’- 10’ long and 7’ wide. He’s dressed in a kind of sackcloth material, hippy kind of homemade clothes, and he’s changing padlocks to this cross. Everybody’s embarrassed – they’re walking by left and right, and nobody’s looking. Except me,” McGuire laughs.

“I come walking out of the door, and he’s looking right into my eyes. I didn’t want to blow my cool, so I said ‘Hey, what’s happening?’ And the only thing he said to me was ‘Jesus.’ That’s all he said. And for the first time in my life, I saw a pure, non-judgmental, compassionate, caring love coming out of this man’s eyes. There was no judgment; no condemnation, no self-righteousness, no disgust. Just pure caring coming from him. I could sense his concern for my well-being. And that totally disarmed me.”

The brief meeting set in motion changes that would result in McGuire adopting a Christian world-view soon after.

Years later, the two would meet again. “The man with the cross was Arthur Blessitt, an evangelist who has traveled the world carrying his 12 foot cross. I talked to him, and he said the only time he did that was one night in October. He’d been arrested the night before for disturbing the peace, so he chained himself to it – figured if they’re gonna arrest him that night they’re gonna have a hard time getting that cross in their squad car.”

As life-changing as it was for Barry, Blessitt couldn’t even recall their encounter. “He didn’t remember. He said, ‘I heard about this, but I don’t remember talking to you.’ And I said ‘You didn’t talk to me, man. You said one word; you just said ‘Jesus’ with your mouth.’”

It was enough, and made for a lesson he’s never forgot. “I tell people this now; if people don’t see Christ flowing out of our eyes, it doesn’t matter what comes out of our mouth. If they don’t see love – non-judgmental love – flowing out of our eyes, we can just stand there and spout scriptures all day long, and it’s just like tinkling cymbals and clanging brass.”

As the seventies dawned, the Jesus Movement – young people out of the Hippie subculture who had accepted Christianity – was growing rapidly, especially in southern California.

Eager converts were looking for cultural evidence of the change, and it seemed any sign would do; songs like James Taylor’s ‘Fire and Rain,’ ‘Spirit in the Sky’ and ‘One Toke Over the Line’ all alluded to Christ on at least a superficial level.

As far as star power – credible, well-known performers identifying themselves as believers – the movement was sadly lacking. Then came McGuire. Granted, it had been a few years since the hits, but he did have credentials, including a #1 record. His early Christian recordings were some of the genre’s most popular sellers, and important stepping stones towards becoming the multi-billion dollar industry it is today.

As far as star power – credible, well-known performers identifying themselves as believers – the movement was sadly lacking. Then came McGuire. Granted, it had been a few years since the hits, but he did have credentials, including a #1 record. His early Christian recordings were some of the genre’s most popular sellers, and important stepping stones towards becoming the multi-billion dollar industry it is today.

McGuire has mixed feelings about the time. He believes the scene was started with the best intentions, but business-wise was disheartening for many of the participants, especially those who had experienced successful careers outside the church.

Dion, Chris Hillman (Byrds) Buddy Miller and Mark Farner (Grand Funk Railroad) were just a few of the performers who eventually left, put off by what they perceived to be a industry even more corrupt than mainstream labels. “Oh,” McGuire readily agrees, “it is. It was for me.”

Going in, he was convinced this ‘Christian’ version of the music industry would be different – no more broken promises and rip-offs.

“Well, we didn’t think it was,” he laughs, “but it turned out to be, didn’t it? We went in very naïve, thinking it was all for the Lord, and now we can all trust each other.”

Somebody was certainly making money; McGuire’s Christian catalogue includes ‘Cosmic Cowboy,’ which held the #1 position for an astounding 35 weeks in 1978-1979. [A little perspective; the longest-ever charting pop single equivalent was 16 weeks].

Outside of one album (1989’s Pilgrim), he signed away the rights to his recordings. “All my old stuff – all my Christian stuff – was on Word Records and Sparrow Records, and then they sold everything to other companies. It took me four years and $10,000 to get [1975’s] To The Bride back in print.

“I lost Bullfrogs and Butterflies [a 1980 children’s album] because I gave it to a ministry, and the CEO of the ministry stepped down, started his own profit-making business – and then he bought the masters for his own company. So he wound up with all the masters that all these different people had given the ministry; he personally owns them all.” That album alone sold over three million copies.

He recalls the hard lesson learned; “We’re all one in Christ, and then they steal your money.” There were rare times when he did witness real Christian ethics; “Occasionally. But not from the business people; only from the artists. My fellow ripees,” he laughs.

Of the many relationships from the era that have endured, his marriage is particularly impressive. Next month McGuire and his wife Mari will celebrate their 35th wedding anniversary. It’s his forth marriage. The difference, he claims, is simple; “Christ. The other three were before, and there was no foundation for a relationship. It was just built on ‘Hey – let’s get married! Let’s hang out together.’ In fact, then I gave up on marriage.”

But not on relationships, per se. “I have two children with two different ladies I wasn’t married to. My son was born between my second and third marriage, and then, after my third marriage, I just gave up. I thought; ‘That’s stupid.’”

In McGuire’s case, the fourth time was the charm; “35 years in November – and still good friends! We’re having a lot of fun hanging curtains; Mari’s been sewing, putting in the pleats, and I’ve been putting up the rods,” McGuire chuckles, “and, you know, we just work together all the time.” The couple travel together on all of Barry’s tours.

In McGuire’s case, the fourth time was the charm; “35 years in November – and still good friends! We’re having a lot of fun hanging curtains; Mari’s been sewing, putting in the pleats, and I’ve been putting up the rods,” McGuire chuckles, “and, you know, we just work together all the time.” The couple travel together on all of Barry’s tours.

Economics aside, he was happy to accept the status quo within the Christian community for the first two decades. Then things began to change.

“I tried to pound a round peg into a square hole for years, and it just didn’t fit. There were too many loose ends; too many loose ends. I just couldn’t handle the [contradictions] so I wouldn’t think about it. Because I couldn’t get a straight answer.”

He’s long been frustrated by a church that proclaims the gospel, but rarely lives it. “You see it all the time on TV. I still see it. I mean, that’s all I see of Christianity.

“I believe what Christ had to say, but I get the feeling the church has taken the words of Jesus and manipulated them – and used Christ – to build their own little empire. And if you don’t do what they say to do, and you don’t come to Christ the way they say you’re going to, you’re going to burn in Hell.

“This is tragic, but it’s like people who call themselves by the name of Christ are filled with fear. I can’t understand how people who are forgiven – why there’s so much fear in their lives. They fear everything.

“They fear the economy, they fear the price of gas, they fear what kind of food they’re eating. They fear dying. They fear other spiritual doctrines. If you’re sure of your doctrine, then where’s the fear?

“We’ve never been taught how to get the beams out of our own eyes. I’ve had to go to other sources to find the tools to de-beam myself. To recognize, where scripture says; ‘Search me, O God…to see if there be any wicked way inside me.’ [Psalm 139:23-24] What does that mean? Well, when I judge anybody as being a homosexual, or I judge somebody as being of another race, or a lower caste, well, that’s a beam. That’s a beam in my eye, so I’m not seeing them as a human being, as a child of God. How dare I judge anyone that Christ died to forgive?

“See, this is my thing; we were slaves to sin, right? So Christ came along and bought us from our slave master. Paid for us with his own life and blood. So we don’t belong to that guy anymore. We have a new slave master who loves us. Now, when a slave is bought and sold, does the slave have any say in it?

“Even if he doesn’t know he’s free, he’s free. I mean, he can go on and live in hell and live a perverted, miserable horrible life, and he will suffer the consequences of those decisions that he makes. But spiritually, he’s been bought and paid for.”

He references one of the most renowned Bible stories; “Just like Saul on the way to Damascus; he was on his way to murder some more Christians. And Christ stopped him on the road and says ‘Why are you persecuting me?’ He’d heard the sermons. He’d heard the gospel. He knew the gospel of Christ – he’d rejected it. But Christ revealed himself personally to Saul. And Saul said ‘Who are you?’ And then Jesus revealed who he was and then Saul’s heart was transformed from a heart of stone to a heart of repentant flesh.”

“How can people be held accountable for rejecting a Christ that is a false Christ? It’s like the church has kidnapped Jesus, and locked him up in the back room. He doesn’t belong to the world anymore; now he belongs to the church. And the only way the world can get to Jesus is to come through the door of the church and jump through all the hoops. Step the steps, walk the walk and talk the talk. And then they can have Christ. And I just don’t see that. I think Christ died for everybody.”

He’s confident in his stance, although unwilling – and uninterested – in arguing the finer theological points.

“I don’t know how it’s gonna work, but I know that God is going to reveal himself to every person. And when they wake up on their road to Damascus, and see the real Christ – maybe it’s the point where our spirit leaves our body – every knee will bow, every tongue will confess; ‘Oh Lord God, oh my God.’”

Some groups, he maintains, model the biblical idea of community far more effectively than today’s church. Like Alcoholics Anonymous. “I used to go to A.A. meetings with a friend of mine in Hollywood, and one night we were standing there – this is many years ago, when I first started waking up to [realizing] something’s wrong. And I’m standing there, we’re saying The Lord’s Prayer at the end of the meeting, and I’ve got two gay guys on my left side, and two lesbians on my right side. We’re all holding hands along the row, and we’re all saying; ‘Our Father which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name…’ And I started to cry.

“At A.A. meetings nobody’s paid, they don’t own any buildings, there’s no permanent leader. It’s a support group. And they support each other; ‘Here’s my number; don’t drink. If you feel like you want to drink, call me. I don’t care, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, I’m available to you.’ We don’t do that in church.”

His frustration is readily apparent. “All this has just come about in the last 10 years. For 20 years I tried – like I say – to pound a round peg into a square hole. And finally I just said ‘This doesn’t make sense. I’m sorry, I can’t; I just don’t believe this. I’m sorry.”

McGuire’s current philosophy makes room for a variety of seemingly disparate views. To illustrate, he shares a popular analogy. “Take 1,000 people, and put them holding hands in a big circle. In the middle of them you put an elephant. And ask each person ‘What does the elephant look like?’ Every person is going to give you a different description. Even your left eye sees the elephant a little bit different than your right eye. It’s a different perspective. That’s why we have two eyes. And two people – that gives you a better description. Eight people gives you a better description of what you’re looking at. So instead of rejecting what the left eye sees, what if we opened both eyes? What if we opened all 2,000 eyes, and accept what everybody sees as exactly what they see?

McGuire’s current philosophy makes room for a variety of seemingly disparate views. To illustrate, he shares a popular analogy. “Take 1,000 people, and put them holding hands in a big circle. In the middle of them you put an elephant. And ask each person ‘What does the elephant look like?’ Every person is going to give you a different description. Even your left eye sees the elephant a little bit different than your right eye. It’s a different perspective. That’s why we have two eyes. And two people – that gives you a better description. Eight people gives you a better description of what you’re looking at. So instead of rejecting what the left eye sees, what if we opened both eyes? What if we opened all 2,000 eyes, and accept what everybody sees as exactly what they see?

“I don’t see it that way, but they do. And God’s a pretty big elephant. Some people look at the elephant and think its Buddha. Other people look and think its Krishna. Other people think its Mohammed.

“But we’re all looking at God here. It doesn’t matter what language you speak or what country you were born in; there’s only one God, and we’re all looking at him from a different angle, so let’s all lighten up on each other. Maybe, if we all accept what everybody’s seeing is what they see – how they perceive reality is their reality – then maybe we could all get a little bit better understanding of what God looks like.”

In part, McGuire attributes his change in outlook to a handful of books that lie well

outside the traditional Christian canon. The most important, by far, is The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle.

“Everything he said gave me tools to become more like Christ. To take no thought for tomorrow, living in the moment. My only access to God is through this present moment. Everything that’s alive, is alive right now. It’s not alive yesterday and it’s not alive three minutes from now. So this present moment is all we have. Everything else is a virtual reality in our mind. It’s mind-created. Time is mind-created. There is no such thing as time; there’s only now. Everything else is virtual projections of fantasies or remembrances of past victories or failures or whatever.

“You know the scripture that says ‘I am the way, the truth and the life?’[John 14:6] Well, that word, ‘truth,’ if you look it up in the original Greek – and I did – if you look that word up in the original Greek, it should have been more accurately translated as ‘reality.’ ‘I am the way, the reality, and the life.’”

The difference being? “Well, truth is kind of philosophical. Truth to you may not be truth to me. Or truth to the both of us may not be truth to an Eskimo, or somebody living in Africa, or somebody living in the desert. Truth is philosophical, but reality is the same for everybody. Reality is what’s real.”

It’s a concept McGuire returns to repeatedly during our conversations. “It’s a 200% reality all of the time; it’s 100% linear, 100% non-linear all of the time. It’s 100% temporal and 100% spiritual all at the same time. 100% joy and 100% sorrow. 100% work, 100% rest. 100% war, 100% peace.”

He offers with a personal anecdote; “I just spent a day with my Grandchildren. Our son-in-law graduated, he got his University Degree, and what an afternoon; it was wonderful. We had lunch, we laughed and talked, and I was trading punches with my granddaughters. But, at the same time, children are starving to death.”

Each situation is genuine. “They’re both real. You can’t just cut off one world and say that doesn’t exist. It’s got to be a total acceptance of both sides; the ying and the yang of it. Because it’s all happening at the same time.”

“And Christianity has a tendency to take one position to the exclusion of all others. Like, they can’t deal with predestination and freedom of choice. So they have to get rid of one, and hang on to the other. So you either become a Calvinist or an Arminianist. Because a Calvinist has to get rid of all the predestination scriptures. And the Arminianists have to get rid of the opposite scriptures. But they’re all there! So you gotta accept both sides of the story all at the same time.”

The irony, McGuire argues, is that scripture teaches exactly that concept: “Christ was a 200% person; he was 100% God, and 100% man. And we are too; we just don’t know it yet.”

While admiring Tolle’s ideas, he did take issue with one aspect of his writing; “I was telling Mari, ‘There doesn’t seem to be too much blood of Christ in this book,’ in The Power of Now.”

Then he discovered The Sacrament of the Present Moment, by Jean-Pierre de Caussade. “It was written 300 years ago, and translated by Kitty Muggeridge, Malcolm Muggeridge’s wife. And man, he’s saying exactly the same thing that Eckhart is saying, only he’s using Christian words.

It’s the unfolding of reality, but he calls it ‘divine action.’ It’s the same thing that Eckhart is saying, but in Christian-ese.

“He was a Catholic Priest, and it so flew in the face of Catholic doctrine, that they wouldn’t translate it properly until Kitty came along and said ‘Wait a minute, this has got to be translated properly.’

“They didn’t want to have it translated,” McGuire chuckles, “because he said ‘We don’t need a Priest. We don’t need a church.’”

He was thrilled by the book. “I bought a whole case of them. I’ve been giving them away to everybody. Mari almost fainted; I had a Visa bill of almost $800! Oh, man. You know, when you get a hold of something, you want to share it with people.”

Don Miguel Ruiz provided more concepts; “He has this book called The Four Agreements. Here’s the thing; tools – how to become like Jesus. First of all, you tell the truth. Your words are impeccably to reveal what you truly think.

“Now, what I think is true today, with additional information, I may not think is true tomorrow. As we grow in our awareness, our understanding of truth is changing. Creation is still in flow.

“See, when God said ‘Let there be light’ [Genesis 1:3] he spoke the Universe into existence. Now, creation is still going on, and I know this to be true, because I just planted some grapevines in my backyard, and they grow a half an inch a day. So the tip of that grapevine is new. It’s never been before. So creation is still going on.

“Creation itself is God’s language, and we need to learn his language. We live in his language. The one who knows everything lives within us, and is revealing around us as reality unfolds. Sometimes, he talks real slow. It may take him maybe 2,000 or 2,000,000 years to say one word.”

Other times, the exact opposite is true. “In a car, somebody pulls out in front of us, and BANG! Well, reality just changed again. So what’s gonna come up out of us then? Are we gonna get angry, start raging? Or are we gonna look at that guy as a brother, as an extension of myself? If I look at him as me, how can I get mad at me? It’s not even my business to forgive anybody. They’ve already been forgiven. It’s my business just to love people.”

Insight can come from the most unlikely sources. “We heard a thing the other night on NCSI, the guy said ‘Until we know everything, we don’t know anything.’ And man, that was our day’s revelation, right there; ‘until we know everything, we don’t know anything.’

McGuire has little regard for fitting in politically or theologically. He continues to perform in churches, but refuses to temper his show. “I don’t know what goes on in people’s minds. I can only share where I’m coming from.”

Reactions have been mixed, with an occasional cancellation, including his old stomping ground, Calvary Chapel. “But then about two months later another Calvary Chapel asked me to come and be the keynote speaker for the National Day of Prayer. So,” he laughs, “I don’t even think about it anymore. It’s just whatever is, is. I can’t control what other people think or do.

“Somebody told me that a Pastor said ‘Well, I hear McGuire’s gone off the deep end.’ And I thought, ‘Praise God, Amen.’ It’s deep unto deep. I am tired of the shallow water. I want to sink deep, deep into God. Just take no thought for tomorrow, no thought of yesterday. Just live Christ…”

McGuire’s new website Trippin’ The Sixties allows him unprecedented personal contact with his audience, with blogs, photos and plans for much more. “It’s awesome. We’re getting about 800 hits a day. We do 50 emails a day. It’s everyone from old Vietnam Veterans to kids that were in college when ‘Eve’ came out. Its Christy Minstrel fans from back in ’63, to teenagers and young people. I mean, ten years old, that love the songs, heard the songs their parents play, and wanna know who I am and what’s going on. They say the baby boomers is your market; well, I don’t have a market. It’s wide open.”

The site offers downloads of his earlier albums, as well as ‘Eve 2.1,’ a 21st Century update of his biggest hit, with old compatriots Roger McGuinn and Mick Fleetwood joining in.

The site offers downloads of his earlier albums, as well as ‘Eve 2.1,’ a 21st Century update of his biggest hit, with old compatriots Roger McGuinn and Mick Fleetwood joining in.

After being on the receiving end of countless shady deals, he takes satisfaction knowing the days of major label strongholds are coming to an end. “Now the money goes in my pocket. I don’t rejoice over anybody’s demise, but I rejoice over that. Artists are finally waking up to fact that we don’t need recording companies. I tell a lot of young artists to do it themselves. It’s better to see 100 records on your own website, than 10,000 in record stores.”

After being on the receiving end of countless shady deals, he takes satisfaction knowing the days of major label strongholds are coming to an end. “Now the money goes in my pocket. I don’t rejoice over anybody’s demise, but I rejoice over that. Artists are finally waking up to fact that we don’t need recording companies. I tell a lot of young artists to do it themselves. It’s better to see 100 records on your own website, than 10,000 in record stores.”

Trippin’ the Sixties is also the name of the live show. Despite his relatively advanced age, he hasn’t slowed down a bit – there are bookings well into the future. He just completed tours of Europe and Asia, and will spend February in Australia. “When you do a show, that’s where you do it – on the road.”

John York, best known for playing bass with Sir Douglas Quintet, and the Byrds from ‘68-’69 accompanies McGuire onstage. The show is a trip down memory lane. “We’re just walking through those years of all those wonderful songs, and all my friends I worked with and performed with and partied with.”

To make the cut, there’s got to be a personal connection. “Every song. I do two Timmy Hardin songs, because he was a friend of mine, a couple of Hoyt Axton songs, John Sebastian, Crosby, Stills & Nash…” The list goes on; “Mamas and Papas, the Byrds, Bob Dylan, Arlo Guthrie…all people that I hung out with.”

To make the cut, there’s got to be a personal connection. “Every song. I do two Timmy Hardin songs, because he was a friend of mine, a couple of Hoyt Axton songs, John Sebastian, Crosby, Stills & Nash…” The list goes on; “Mamas and Papas, the Byrds, Bob Dylan, Arlo Guthrie…all people that I hung out with.”

What made the sixties special? McGuire believes the decade signaled the beginnings of a spiritual renaissance. “After World War II the United States went into a long period of growth. The American dream came true. Most of the people I knew, their parents had two cars in every garage, a swimming pool, and a pool table in the living room. But the moms were all on valium or were closet alcoholics, and the husbands were full-blown alcoholics. They were getting divorces, the husbands had mistresses, and the wives were cheating on their husbands. The kids were watching all this going on, and they’re saying ‘Why should we go to college to get a degree? To get what they’ve got? They’re miserable! I don’t want what they’ve got – this is not what life is all about.’

What made the sixties special? McGuire believes the decade signaled the beginnings of a spiritual renaissance. “After World War II the United States went into a long period of growth. The American dream came true. Most of the people I knew, their parents had two cars in every garage, a swimming pool, and a pool table in the living room. But the moms were all on valium or were closet alcoholics, and the husbands were full-blown alcoholics. They were getting divorces, the husbands had mistresses, and the wives were cheating on their husbands. The kids were watching all this going on, and they’re saying ‘Why should we go to college to get a degree? To get what they’ve got? They’re miserable! I don’t want what they’ve got – this is not what life is all about.’

“And so they left, and thousands of them hit the streets, looking for reality. It was like a volcano erupting – a longing for truth – for relationship with the source from which we came. It built and built and built, and then we had an eruption in the sixties.

“That was a spiritual search. And the music was an expression of the search. The music was an expression of the hypocrisy. That’s all ‘Eve Of Destruction’ was.”

Not that the music of the era was all serious. Much was infused with a sense of joy. McGuire laughs, summing up with a quote from a far distant time; “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

© John Cody 2008