If you ever wanted to make a case for how cruel and unfair the music industry can be – granted, not a tough task – Arthur Alexander would make a great exhibit ‘A.’

He was the only writer in history to have his songs sung by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan. Add Elvis Presley, who covered a number first recorded by Alexander, and you’ve got the four most important acts of the latter half of the 20th century.

He was the only writer in history to have his songs sung by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan. Add Elvis Presley, who covered a number first recorded by Alexander, and you’ve got the four most important acts of the latter half of the 20th century.

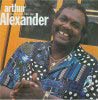

While best known as a writer, his own way with a song – understated, with a melancholic delivery – was exceptional, rivaling the great voices of the sixties. With such a wealth of talent, he should have been a household name.

Instead, owing to the nefarious dealings of a number of individuals, Alexander was unable to sustain a living, and abandoned music in the 70s to work as a bus driver.

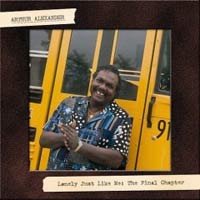

After more than two decades away, he returned with 1993’s exceptional Lonely Just Like Me; but what should have been a triumphant comeback was unexpectedly cut short by his death in June of that year.

After more than two decades away, he returned with 1993’s exceptional Lonely Just Like Me; but what should have been a triumphant comeback was unexpectedly cut short by his death in June of that year.

The disc has now been reissued in expanded form, as Lonely Just Like Me: The Final Chapter (Hacktone) and gives listeners another chance to discover this forgotten gem.

Alexander was born in Florence, Alabama in 1940. His father, a reformed bluesman, spent years toiling in juke joints for little or no money – but quit when his son expressed an interest in playing music himself. “He gave up something he loved to steer me right,” Arthur noted years later.

From then on, his father confined his own singing to the local church. Only gospel music was allowed in the family home, and – in a misguided attempt to thwart any possible interest in music – he forbade his son from learning to play an instrument.

Meanwhile, Arthur was listening to country music on the radio, soaking up classic songs and singers like Hank Williams and Lefty Frizell as well as pop hits of the day.

He joined a gospel group when he was thirteen, which morphed into a cover band a few years later. He began to compose his own songs, overcoming the lack of instrumental skill by singing melodies over and over, until he could hear the whole piece in his head.

His first published song, ‘She Wanna Rock,’ was covered by Arnie Derksen, a Canadian rockabilly singer in 1959. The record didn’t make a dent on the sales charts, but it hardly mattered to Arthur – he was now a bona-fide songwriter.

His own recording career began in 1961 with ‘Sally Sue Brown.’ Later that same year, he recorded ‘You Better Move On’ at Fame studio, a renovated tobacco warehouse in nearby Muscle Shoals, Alabama. It was the studio’s very first recording, and Arthur’s first hit. Fame (for Florence Alabama Music Enterprises) was a rare example of southern whites and blacks working together during the civil rights era. Racism was rampant in the south, but music crossed all boundaries.

Dubbed ‘country soul,’ Alexander’s sound took from his two primary influences, black gospel and white country music. His songs were often mini-morality tales, delivered in a knowing, sorrowful manner. The warmth and purity inherent in his voice was rare even then, and stylistically all-but-forgotten by today’s more over-the-top recording artists.

With a hit record under his belt, life became a blur of constant touring and recording. He charted two more times in 1962, with ‘Where Have You Been (All My Life)’ and ‘Anna (Go To Him).’

With a hit record under his belt, life became a blur of constant touring and recording. He charted two more times in 1962, with ‘Where Have You Been (All My Life)’ and ‘Anna (Go To Him).’

When the British invasion came to America in 1964, the two biggest acts – The Beatles and Rolling Stones – covered his songs.

In 1987 Keith Richards confirmed Alexander’s influence; “When the Beatles and the Rolling Stones got their first chance to record, one did ‘Anna’ and the other did ‘You Better Move On.’ That should tell you enough.”

The Stones included ‘You Better Move On’ on their first EP, and later on the 1965 US only release December’s Children), and the Beatles covered ‘Anna (Go To Him)’ on their debut LP).

Paul McCartney claimed; “That’s what we used to listen to, what we used to like and what we wanted to be like. Black, that was basically it. Arthur Alexander.”

John Lennon was influenced to an even greater degree than the others. His vocal delivery was clearly modeled after Alexander, and Alexander’s frequent use of the word ‘girl’ (‘a good way to personalize the song”) was employed by Lennon on such songs as ‘Thank You Girl,’ You’re Gonna Lose That Girl,’ ‘Another Girl’ and, most obviously, ‘Girl.’ Shortly before his death, Lennon was interviewed by writer Robert Palmer, who noted the contents of Lennon’s jukebox; “…around half of the 45s were early-sixties soul discs by Arthur Alexander.”

Otis Redding, the Bee Gees, Rick Nelson, Dusty Springfield, The Who, Dean Martin and the Moody Blues are just a fraction of the other acts that included Alexander’s songs in their repertoire.

The ensuing royalties should have set him up for life, but a lack of business savvy had resulted in his signing away all his publishing rights at the start of his career. Every cover version was another reminder of the money he would never see.

The ensuing royalties should have set him up for life, but a lack of business savvy had resulted in his signing away all his publishing rights at the start of his career. Every cover version was another reminder of the money he would never see.

Over the next few years he grew bitter. The hits stopped, what money he had made was squandered, and his marriage ended. A 1966 trip to England was a welcome respite, and a career highlight. Audiences treated him like rock royalty, a radical change from his diminished star power at home.

By the late sixties he was recording sporadically and performing less and less. He had developed serious problems with alcohol and pills – mainly amphetamines – and on a number of occasions began to exhibit schizophrenic-like behavior.

After a few drug-related arrests, Alexander was confined to state mental hospital in 1967. There were further breakdowns and return visits – at one point electro shock treatment was administered. In 1971 he was committed for his third and final time after being found naked, stopping cars while high on LSD.

As Bob Beckham, a publisher close to him at the time noted; “Part of Arthur was religious and part of him was a riot. I think his upbringing clashed with what he ran into in the music scene. He was always fighting himself. But he was a good ole boy and I liked him.”

Throughout this period, his singing and songwriting remained strong. He signed with Warner Brothers and released his second LP, 1972’s Arthur Alexander.

Throughout this period, his singing and songwriting remained strong. He signed with Warner Brothers and released his second LP, 1972’s Arthur Alexander.

‘Thank God He Came’ was a highlight. Many of his songs had implied a Christian worldview, but for the first time, he dealt with faith directly; “Hey all you sinners, I’m talking to you/I want you to listen, for I am one too/There was a man from Galilee/He died for you, and he died for me.”

‘Rainbow Road’ and Dennis Linde’s ‘Burning Love’ (covered later that year by Elvis Presley) were equally memorable, but in spite of the quality, the album was met with indifference.

A 1975 recording of his own ‘Every Day I Have To Cry’ (originally a hit for Steve Alaimo) got him back on the charts, but by then he was no longer interested in chasing after success; “I really didn’t like that life anymore, ‘cause by that point I had found religion and gotten myself completely straight.”

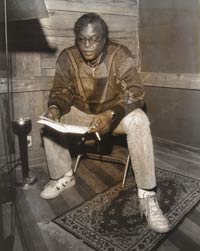

Like his father, he had come back to the church later in life. In 1977 he moved to Cleveland, settling with his second wife into a quiet life far from the spotlight. “When he came here, he changed totally…” she commented, "he matured and settled down completely. He didn’t do nothing but sit around and read the Bible. He read the Bible for years.” He took a job driving bus, moping floors and counseling at-risk youth for a family centre.

He rarely performed, and invariably turned down offers to record again. None of his new friends were even aware of his past as a musician. But he wasn’t forgotten. Others continued to record his songs, most notably Bob Dylan, who covered ‘Sally Sue Brown’ on 1988’s Down In the Groove.

In 1991 he was invited to appear at the Bottom Line in New York City as part of an ongoing series showcasing songwriters singing and discussing their work. The appearance was a phenomenal success. By all accounts he was in better voice than ever.

Danny Kahn from Elektra Records was in the audience that night, and became determined to get him back in the studio. Producer Ben Vaughn was dispatched to Cleveland to meet with Alexander.

As Vaughn recalls, “At dinner, I told him I didn’t blame him if he didn’t want to get back in the business. His life seemed like a good one. He was born again, without feeling the need to convert everyone in sight, and enjoying driving a bus and working at a center for disadvantaged kids. Why would he want to give that up?”

Alexander agreed to record, provided there would be no follow-up tour. “I’m glad to make another album,” he commented at the time, “but I don’t want to stray too far from home, or my grandchildren, or the kids in my community who I’m trying to keep on a good path.”

He was sure this would be different from his previous experiences. “I believe in this record, and I believe in the company that’s handling it. Because I believe in God, and I don’t believe he would have led me back into the same thing that would’ve destroyed me in the beginning.”

Vaughn assembled a first-rate backing group for the sessions, bringing in many of the original Muscle Shoals players, including Dan Penn, Spooner Oldham and Donnie Fritts. Along with revisiting a few of his earlier songs, there was a wealth of new material.

Right from the opener, ‘If It’s Really Got to Be This Way’ – which neatly encapsulates the typical Alexander approach with the refrain; “I’ll cry, but I’ll get by” – it was clear his gift had never left.

The disc closed with a song he claimed had called him out of retirement. ‘I Believe in Miracles.’ The song, he commented, “is about my real life experience with God….God was right there in my head singing that song, and hearing Him sing like that has really helped me carry on. It’s a big reason why I’m singing again today.”

The lyric was crystal clear as to where he stood; “I believe our Lord is a miracle/the light of the world for all to see/who believeth on him/the truth shall make you free.”

Alexander insisted the sessions begin with the song, and when the label later suggested leaving it off the album, he was adamant that it remain. “I believe the song was… [given] to me to exploit. I think I’m a tool, like Moses. He used Moses to take the word to the people, and me, in a far less way. I’m just saying what’s real.”

The disc met with rave reviews, many critics claiming it as one of the highlights of the year. Offers for live appearances came flooding in. Alexander accepted a limited number of engagements, and on June 6, 1993 – the same week the album was officially released – played his first full-length show in Nashville.

The disc met with rave reviews, many critics claiming it as one of the highlights of the year. Offers for live appearances came flooding in. Alexander accepted a limited number of engagements, and on June 6, 1993 – the same week the album was officially released – played his first full-length show in Nashville.

The next day he signed papers that would ensure – for the first time ever – that he would be paid for his songs, righting a 30-year wrong. Within minutes of completing the paperwork, he collapsed and was rushed to the hospital, where he died three days later.

The next day he signed papers that would ensure – for the first time ever – that he would be paid for his songs, righting a 30-year wrong. Within minutes of completing the paperwork, he collapsed and was rushed to the hospital, where he died three days later.

Vaughn was at his bedside; “We were all torn up, but he seemed oddly OK with the whole thing. There was a faint smile on his face in that hospital bed – the look of a man finally at peace. It was a beautiful thing to witness.”

The reissue is given a deluxe treatment. The producers have gone all out with the packaging, a heavy cardboard gatefold sleeve including press releases, photos, session notes, original and updated liner notes, and – sadly – a facsimile of his funeral program.

In addition to the original album, a live session originally broadcast for NPR’s Fresh Air is included, along with the demos Alexander sang for Vaughn in his hotel room the night they met. The disc ends with the very performance that led to the album, a live recording of ‘Anna’ from the Bottom Line in 1991.

Lonely Just Like Me was one of the highlights of 1993. Fittingly, this deluxe, expanded edition is one of the finest reissues of 2007.

(Quotes come from Get A Shot of Rhythm and Blues: The Arthur Alexander Story, by Richard Younger (University of Alabama Press) and liner notes for Lonely Just Like Me: The Final Chapter)

© John Cody 2007