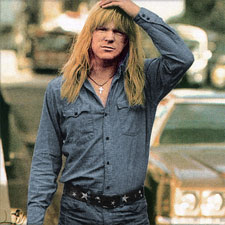

Larry Norman’s importance to the fledgling Christian rock music scene is hard to underestimate. In the late sixties and early seventies, as the Jesus People movement brought thousands of young people back to the church, Norman’s music reflected the radical changes taking place.

Larry Norman’s importance to the fledgling Christian rock music scene is hard to underestimate. In the late sixties and early seventies, as the Jesus People movement brought thousands of young people back to the church, Norman’s music reflected the radical changes taking place.

Pop music had the Beatles, Stones and Dylan; Norman seemed to represent a sanctified version of all three – a ‘righteous rocker,’ to use the title of one of his songs. 1972’s Only Visiting This Planet tops lists as the single best Christian album of all time, and songs like ‘I Wish We’d All Been Ready,’ ‘Why Should The Devil Have All the Good Music’ and ‘Why Don’t You Look Into Jesus’ captured perfectly the fervent, last-generation mindset that typified the times.

When Norman died in early 2008, the tributes were heartfelt. This paper called him “a solid rock in the history of Christian music.”

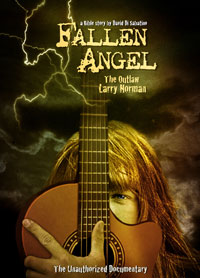

Fallen Angel: The Outlaw Larry Norman offers a radically different view of the man. It’s a tragic tale, told by dozens who were there – each offering their own take on a life lived at odds with what was preached. Key participants from every phase of Norman’s career offer a remarkably consistent story of questionable behavior – including fathering a child he barely acknowledged, and refused to support.

It is, at times, a scathing indictment of a church’s refusal to confront – and an equally powerful testament to the healing power of forgiveness.

If Norman hadn’t loudly proclaimed himself a Christian, there wouldn’t be a story. “It would be nothing. This is no big deal,” Angel director David Di Sabatino readily admits. Many entertainers live lives far removed from their public image. But the fact he held himself – and others – to a higher standard changes everything.

“We all know of people that are ten times worse than he was. That’s not the point. The interesting thing is the mystique that he spun about himself. He was desperately trying to create this mythology that suggests that he was living this superstar Christian life, that ‘I don’t do anything that’s wrong.’ And he just doesn’t admit to anything. When faced with the challenge that this is your son, he doesn’t admit it.”

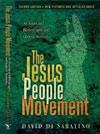

Di Sabatino was well qualified to take on this project. He holds degrees from both Eastern Pentecostal Bible College and McMaster Divinity College, and is the author of The Jesus People Movement: An Annotated Bibliography and General Resource (Jester Media); and director of Frisbee: The Life and Times of a Hippie Preacher.

Despite the moral failings, he believes Norman was an effective communicator of Christian story. “He understood the gospel message properly. That’s the thing; when he was lucid, and he was on – and he was having a good day, when the nice Larry was out – he was as good as anybody.

Di Sabatino likens Norman to the Old Testament figure Jacob, a broken man who nevertheless managed to move others towards God.

“Jacob is a good analogy because here’s a guy that’s jukin’ and jivin’ all over the place, and still is the father of Israel – just like Larry was the father of Contemporary Christian Music. But then [Jacob] turns up in his dying days, saying ‘My days are not as long as those of my ancestors, I have had a hard time of it because of my actions’ – something like that. And he realizes that these things that he’s done – jerking his mother around, jerking his father, jerking his brother around – aren’t exactly the way to go. I think that’s the story here.”

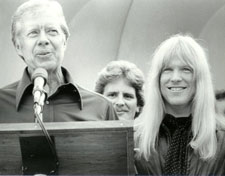

By the time Norman joined People – a San Jose sextet who hit the top 40 with a cover of the Zombies’ ‘I Love You’ in the summer of 1968 – his propensity for spinning stories was already in effect.

By the time Norman joined People – a San Jose sextet who hit the top 40 with a cover of the Zombies’ ‘I Love You’ in the summer of 1968 – his propensity for spinning stories was already in effect.

Band members maintain they were never even aware he was a Christian. They were, however, frustrated by a tendency towards secrecy and self-centeredness, and eventually fired him from the group. Norman turned the incident around, claiming he had quit, forgoing surefire commercial success in order to stand up for his faith.

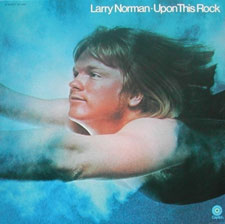

The following year, he recorded his debut solo release, Upon This Rock. Despite claims to the contrary, it was not the first album of Christian rock music. A number of bands were already playing the style, significantly, Agape, who Norman had seen performing in Hollywood the year before.

Around the same time, he took credit for inventing the One Way sign – a finger pointed toward heaven – and copyrighted the logo before being taken to task by church elders, well aware it was the creation of another member of the same congregation.

Around the same time, he took credit for inventing the One Way sign – a finger pointed toward heaven – and copyrighted the logo before being taken to task by church elders, well aware it was the creation of another member of the same congregation.

Some of Norman’s more fervent fans simply refuse to accept that their hero had feet of clay. “I think for them, truth on first gulp is very difficult.” The fact that those who knew him best – musicians, management, record company staff, ex-finances and wives – all tell the same story, hardly seems to matter.

“They can’t separate the fact that he touched their lives, and yet lied – or did things that were aslant. And we’re not just saying the normal kind of…everybody has crap in their lives. It’s things that make you wonder – the stuff that he’s doing to his best friends, and the fact that he has a child that he neglects.”

Instead, they blame Di Sabatino himself. Some have been particularly hostile. “That has been difficult,” he admits, “to hear total strangers jump in your email box, and they’re swinging from the get-go.”

At one point, he questioned whether it was worth the effort, and sought out Christian broadcaster Rich Buehler for advice.

“I said; “Am I crazy here? I know I’m going to get lambasted, and people aren’t going to like this. Should I even do this?’”

Buehler was unequivocal and to the point.

“He said: ‘David, anything that is going to breathe truth into the Christian church at this time, needs to be done. It doesn’t matter what the cost is. Stand up.’ And that was it, I turned the corner.

“Truth never needs to be defended. I know what my heart has done, and why I did this. I didn’t lie, and I didn’t make any of this stuff up. It’s the truth; deal with it. And if we are people of the truth, then we should be the first ones telling these stories, not covering them up.”

Fallen Angel is Di Sabatino’s second feature. Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher told the story of Lonnie Frisbee, a Jesus Freak evangelist who brought thousands to faith, all the while struggling with his own personal issues. Both films are powerful testimonies to the notion of God using unlikely characters to grow his kingdom.

Fallen Angel is Di Sabatino’s second feature. Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher told the story of Lonnie Frisbee, a Jesus Freak evangelist who brought thousands to faith, all the while struggling with his own personal issues. Both films are powerful testimonies to the notion of God using unlikely characters to grow his kingdom.

“I don’t get it,” Di Sabatino admits. “Some of the angriest responses, I was just dumbfounded. I was like; ‘You should be reveling in the fact that God used these guys, and you just can’t see it. You think I’m the enemy because I’m saying it. Yet this resonates with everything that we read in the Bible. How can you be so angry about this?’

“Now, I’m realizing that I’m doing something totally new here. Which is funny; we’re supposed to be truth tellers and all that? I find there’s more BS in the Christian market than anywhere else. I am so horrified that we are the biggest liars on the block. I haven’t spent a lot of time in other communities, but I can’t imagine – I can’t imagine – a more dishonest community. I just don’t get it.”

It’s an all-too familiar story; covering up questionable behavior inside the church to keep up appearances. “The Faustian deal that Christians make is a bad one. They say; ‘As long as people are hearing about the Lord, we don’t care what the guy does.’ And that’s a horrible deal. It’s going to reap havoc every time.

“We’re selling this malarkey to the world that says we’re different, and we’re putting ourselves in a Catch-22 situation, where we say ‘if you just come to Jesus, everything is okay, and your life changes.’”

It makes for a shallow, simplistic gospel. “It’s just nonsense, but it’s what the people want to hear. They want to hear: ‘It’s so wonderful, and if you just listen to this, it will change your life.’ But it’s just not true. It’s not true. Yes, it changes your life, but Welcome To the Jungle. That’s when we should play that song. It’s tough. This is a tough thing to do, and you’re going to fall. You’re going to go back like a dog to its vomit. And you’re going to struggle, and you’re going to do all those things. But we don’t say that. We say it’s all smooth sailing. So when somebody falls…”

Di Sabatino’s disdain for sound bite theology is clear and unabashed. “We don’t even have our own polemic straight. We don’t have a complexified understanding of the faith. We have these little crib notes. And it just doesn’t work. You cannot package it like that. It just won’t work.

“And that’s why I like telling these stories; because – in spite of that – God still works through this guy. Even if he only gave God 10% of his heart – the other 90% is a damn shame – but that 10% does some wonderful things.”

In many respects, Angel is surprisingly generous towards its subject. “At the Cinequest Film Festival [San Jose], some of the people that had surrounded Larry for the last 15, 20 years of his life came up to me, and apologized. After they saw the film, they said ‘We thought this was going to be an expose where you just lambasted him.’ And I didn’t do that. I could have easily done that – it would have been very, very easy. And there were a lot of voices in my ear that were asking me to do it. But I respected Larry Norman enough, that I believe that at some point he was sincere. And that he lost his way. Something happened, and he lost grip on his first principles, as Randy Stonehill says in the film.”

In many respects, Angel is surprisingly generous towards its subject. “At the Cinequest Film Festival [San Jose], some of the people that had surrounded Larry for the last 15, 20 years of his life came up to me, and apologized. After they saw the film, they said ‘We thought this was going to be an expose where you just lambasted him.’ And I didn’t do that. I could have easily done that – it would have been very, very easy. And there were a lot of voices in my ear that were asking me to do it. But I respected Larry Norman enough, that I believe that at some point he was sincere. And that he lost his way. Something happened, and he lost grip on his first principles, as Randy Stonehill says in the film.”

Norman’s promiscuity, for instance, was never part of the film’s mandate. “I don’t care if he wanted to nail everything that moved. That doesn’t matter to me. If that’s the way you want to live your life, go and live your life that way. Because he was never saying that you shouldn’t do that. I never heard Larry talk about being sexually monogamous, so I’ve got no problem with that. But when you have a kid that you never take care of, that’s way out of line. That’s a problem.

“But there was never any desire or thought on my part, that; ‘We’ve got to fix Larry’s wagon.’ His wagon was fixed by his own actions. I knew that from day one. You can’t live your life like that and not have repercussions. And you feel extremely sorry. I came away finally having my ‘Aha!’ moment, going ‘Okay, I get it; I get why he’s doing this,’ and how sad. Because it’s out of tremendous hurt and pain that he’s lashing out at other people. I can’t even imagine what happened to him, to make him like this. And it made me feel sorry for him. And ultimately, at the end of the day, it’s not this larger-than-life character. it’s this short little Gollum-like man who comes away. And you’re left thinking of what could have been, if he’d only have dealt with this stuff.”

At times, Norman’s self-mythologizing bordered on the incredulous. Ironically, one of the most outrageous claims – that he inspired Pete Townsend to write Tommy after the latter heard People perform ‘The Epic’ – may actually contain some truth. ‘There’s shards of that that are might be true. One of the guys in People, [bassist] Robbie Levin – who didn’t like Larry – says he operated a lodge, and Townsend came to stay once, and he asked him point blank, and Townsend corroborated that it was true.’ [Note: in the original version of this piece, ‘Epic’ co-composer Denny Fridkin was cited rather than Levin. Levin is the correct source. Fridkin – who remained friends with Larry – simply related Levin’s story to Di Sabatino].

“That’s the problem with Larry. It’s hard to figure out when he was actually telling the truth, and when he was spinning a story. He’s given you ample opportunity to not believe anything that came out of his mouth, but there were times when he did tell the truth. So on the occasion that he does, you’re sitting around going ‘Yeah, right.’ But some of it’s true. He did have moderate success. There was some talent there. The problem was he tried to magnify it all by himself, and blow it up all by himself.”

Viewing Angel can be a sobering experience for those that bought into Norman’s self-aggrandizing.

“There will be a handful that will always see a conspiracy behind this, and that’s fine. But I think that once people see the movie, they will let it resonate, as hard as it is. Somebody wrote me with a quote from one of the presidents; ‘The truth will set you free, but first it makes you miserable.’ And I think that’s true in this case.”

“There will be a handful that will always see a conspiracy behind this, and that’s fine. But I think that once people see the movie, they will let it resonate, as hard as it is. Somebody wrote me with a quote from one of the presidents; ‘The truth will set you free, but first it makes you miserable.’ And I think that’s true in this case.”

“I had a guy who was a huge Larry Norman fan, who wrote me and said ‘I hope the movie isn’t about just you bashing Larry…’ After watching the film, he wrote again; “And he just couldn’t get it. He wasn’t necessarily mad at me, he was like, ‘How could Larry have done these things?’ And then I got a letter from his wife, who watched the movie with him, and she said ‘Thank you so much, because he has gone on for years about how wonderful this guy was. And I knew deep down that there was something wrong with him. And your movie really hurt him, and it really has shaken him, but it’s put him in a better place.’”

That’s the point in making these films, he argues. “Because, if our faith is dependent on these guys being larger than life, then it’s good that somebody pulls the rug out from under them, so they can re-evaluate their faith and put it back together again, the right way.”

Di Sabatino started as a fan himself; Norman’s music provided the soundtrack to his early Christian journey. “It hit me young; I was 14. I was a kid, and searching for a voice that resonated with my counter-cultural take on things, knowing that the church quite wasn’t telling me the truth. And it was huge in my life at that time, and rightly so. Because those songs, for the first five or six years of my Christian faith – when I started taking it seriously – that was what it was about. It was about those songs resonating through my brain.”

Di Sabatino started as a fan himself; Norman’s music provided the soundtrack to his early Christian journey. “It hit me young; I was 14. I was a kid, and searching for a voice that resonated with my counter-cultural take on things, knowing that the church quite wasn’t telling me the truth. And it was huge in my life at that time, and rightly so. Because those songs, for the first five or six years of my Christian faith – when I started taking it seriously – that was what it was about. It was about those songs resonating through my brain.”

Eventually, the music lost it’s attraction. “I haven’t been able to listen to his stuff in the same way for a long time. I had my moment in 1990 when I got rid of all my collection.” By then there were just too many discrepancies to ignore. “He ruined it, and I realized. I had a pretty good collection; I sold it for a year’s worth of Seminary, so it was a good deal; I did good there.

“It was only in 2000, that I came back to him. I remember listening to Street Level, and just weeping, because it had been so powerful in my life, but this guy had become so bizarre. And I was always saddened by that, because he started out to be something so larger than life. What in the world happened? The songs were great.”

For an audience eager to hear the gospel message combined with rock sensibilities, the songs were made to order.

“Larry was an assimilator. He was good at looking at the culture and saying ‘What is it that they want? They need a song – an apologetic for Christian rock music.’ Okay: ‘Why Should the Devil Have All the Good Music.’ It was a line on the back of a Randy Matthews album. He lifts the line – which is fine – there’s nothing wrong with that. I’m sure that he took a line from here and a line from there. Like all music. He was astute on the rock ‘n’ roll world that borrows. The Rolling Stones and Chess Records, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot and Bob Dylan… Larry did the same thing. But he put it together in a way that was amazing, and he had a lot of songs coming out of him.”

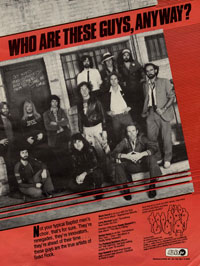

In the early 1970s, Norman set up Street Level Booking Agency and Solid Rock Records. The stable of acts – including Randy Stonehill, Mark Heard, Steve Scott, Tom Howard and the band Daniel Amos – was unequalled on the Christian music scene. With the exception of Heard (who passed away in 1993), all are interviewed for the film, each recounting stories of betrayal, dysfunction and missed opportunities.

In the early 1970s, Norman set up Street Level Booking Agency and Solid Rock Records. The stable of acts – including Randy Stonehill, Mark Heard, Steve Scott, Tom Howard and the band Daniel Amos – was unequalled on the Christian music scene. With the exception of Heard (who passed away in 1993), all are interviewed for the film, each recounting stories of betrayal, dysfunction and missed opportunities.

In the case of Daniel Amos, Norman delayed the group’s breakthrough, Horrendous Disc, for almost three years, only releasing it after they had left the label. Di Sabatino believes it was shelved for one simple reason – Larry saw them as a threat.

“I think that Larry brought Daniel Amos close, just because they were one of the most popular bands at the time. He brought them in just to derail their careers. Of course, Larry would point to all these things, about how he was trying to help them and all of that; B S; I think Larry Norman was into Larry Norman, and any band that was going to derail him, or take away from his light, was a threat.”

One of the first hard rock bands on the Christian circuit, JC Power Outlet had already released two LPs when they signed with Solid Rock. “Why does he change their name? They were one of the big bands at the time. They were a tracking band, they were good. He brings them close, and he changes their name to Pantano-Salsbury. From JC Power Outlet! So he can say, ‘Well, I was trying to help them.’ And their record didn’t sell.

“There’s stuff going on there that doesn’t make sense until you hear the whole story. And then you go; Oh my God; he was not only sabotaging everybody else’s career, he was sabotaging his own career.”

It’s one thing to see others as a threat – but why destroy his own career? “That’s the million dollar question. I don’t know. I talked with Philip Mangano, who was his manager. He’s a player. He’s a very bright man, and he’s interesting. Philip is a bright guy – this is a bright man.’”

Today, as the Executive Director of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, Mangano is one of the most powerful voices in Washington. He was more than qualified to bring to fruition the Solid Rock vision of artistic excellence and integrity.

“Mangano was like [U2 manager] Paul McGuinnis; he was looking towards creating something like that. He was sending these people out, making money for them, doing what he was supposed to do, with the hopes that eventually, they were going to get to a place where they could then in turn kind of become this larger-than-life company. The problem was, you had Larry, who was actively mucking things up.

“Philip had three book deals for Larry. There was going to be a biography that Word Records was going to publish, a book of photos taken by Larry, and a picture book of pictures of Larry. All of these things were going to come out at the same time. Larry said no to it all. Larry said no. And Mangano is standing there, going; ‘I had all this stuff…’”

Given the level of talent, the Solid Rock roster was cable of far more than was ever realized. “They were good. Let’s be honest; they could have been doing what U2 did. He was an influence on those guys early on. U2 definitely had their radar up – they knew about Larry.”

A crucial distinction being that U2 modelled a far more transparent image, showing their fallible, human side all along. “That’s the difference. Solid Rock was a wonderful idea. It was a great idea of guys coming together. The problem being that the centre didn’t hold, because you had a wonky guy at the centre. He just couldn’t get around and realize that it wasn’t just about him. He couldn’t get outside of himself. And that’s the tragedy of it all.”

Mangano and other staff admit to protecting Larry’s public image – spinning stories themselves – in a vain attempt to keep the label’s ideals alive.

Mangano and other staff admit to protecting Larry’s public image – spinning stories themselves – in a vain attempt to keep the label’s ideals alive.

Things finally fell apart in 1979, after it was discovered Larry was cheating on his wife – and having an affair with Randy’s wife. An intervention was instigated by the Solid Rock staff and artists. “That meeting was very important. In the aftermath, he spins out. You have to understand, in Larry’s head, he’s got a whole different world going on. He’s so upset that these people that he’s created, given opportunity to, helped establish – that owe their careers to him – now question him. And he doesn’t want any part of that. It’s like ‘You should be thanking me perpetually. I can do whatever I want.’”

Di Sabatino thinks Norman truly believed his own claims. “There’s part of his psyche; that whatever he said, he believed. He buys it himself. So if it’s a story that he tells that isn’t true, or is a half truth, somewhere along the line – ten minutes, an hour, a week, a year – it starts to become the gospel according to Larry Norman. If you question him, he’d look at you like, ‘What are you talking about?’ He’s writing his own history, but he really believes it as he’s telling it.

“Randy says it best; you could see in his life that he had this stuff [issues], that he was capable of this stuff, yet he was somehow holding it back. It was bubbling under the surface, but he was keeping it under wraps. And then, when those people turn on him – in his mind – and ask him questions and ask him to account for his behavior, that’s it. The lid is off. Forever more, he’s constantly caught up in this spin mode, where he has to explain, has to explain, has to explain. To the point of ad nauseum, just, ‘Larry, let it go.’ And part of that was his upbringing, and part of that was his need to be heard.”

A decade later, Norman continued the spin. In a 1989 CCM Magazine interview, he claimed to have stopped his label mates from releasing albums because “all of the artists were leaving their wives.” The magazine issued an apology after a barrage of complaints.

Di Sabatino laughs. “With Larry – to unravel ‘Larrryspeak’ – you have to turn everything around, because he’d turned everything inside out and backwards, and made it about him. He was having marital problems. I don’t know that they were all having marital problems. But he was certainly not the high priest of this place, yet that’s how he acted. Like he was the spiritual father figure, when in reality, he was the worst of the lot.”

As every act left Solid Rock – in many cases going on to far greater success – Larry’s own releases suffered a decided drop in quality. “In 1980, it just stops. He had a ten year prolific period where he’s just writing songs left right and centre – and good songs. And then, nothing. After 1980, he’s nothing. He’s just doing crap out of his garage. He’s not doing anything of merit.”

It only got worse. “By the time you get to the late 80s, early 90s,” Di Sabatino laments, “Larry becomes a cartoon character.” Rather than create new music, he began to re-record the songs that had made him famous. “It became more important for him to spin his story.”

The relationship between Norman and Stonehill is particularly fascinating. Early on, Larry took Randy under his wing, ostensibly protecting him from the shadier side of the music industry – and subsequently took his song publishing.

The relationship between Norman and Stonehill is particularly fascinating. Early on, Larry took Randy under his wing, ostensibly protecting him from the shadier side of the music industry – and subsequently took his song publishing.

“You have to understand Randy; he’s a nice guy, but he doesn’t want to confront. I think in the beginning, their relationship was mutually beneficial, but at a certain point, it turned. And Randy didn’t have the capabilities to turn around and say ‘I want what I want.’

When Norman issued Stonehill’s Solid Rock albums on CD, the revised liner notes– crediting himself for photos, concepts, arrangements, even songs – implied Randy was little more than a bystander at his own recording sessions.

“He was always trying to tweak Randy with stuff like that. And Randy – to his credit – just let it go. In my understanding, Randy is a little bit too passive in regards to this. He should have fought Larry; he had every right to do it, and he would have won.” Describing him as a “hollow man,” who simply didn’t understand intimacy, nor possess the capacity to be a friend, Stonehill claims it’s still hard to talk about Larry, 25 years after their falling out; “How could he have let it go down that road?…Here was a guy who led me to the gates of Heaven…”

“He was always trying to tweak Randy with stuff like that. And Randy – to his credit – just let it go. In my understanding, Randy is a little bit too passive in regards to this. He should have fought Larry; he had every right to do it, and he would have won.” Describing him as a “hollow man,” who simply didn’t understand intimacy, nor possess the capacity to be a friend, Stonehill claims it’s still hard to talk about Larry, 25 years after their falling out; “How could he have let it go down that road?…Here was a guy who led me to the gates of Heaven…”

He questions a highly publicized on-stage reunion between the two in 2001, speculating whether it was simply a ploy to garner publicity for Norman’s by then waning career.

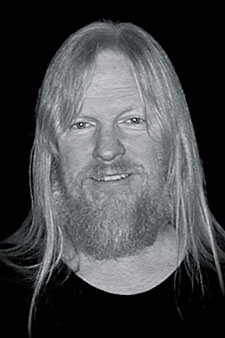

The most heart-wrenching sequences in Fallen Angel deal with a son born out of wedlock. Di Sabatino claims Daniel Robinson is Larry’s child with Jennifer Wallace, a concert promoter and back-up singer who travelled on an Australian tour in the late 1980s.

Initially, Larry appeared overjoyed at the prospect of being a father. “He kissed her belly on his way out of Australia, and with tears in his eyes, said ‘I’ll see you for when the kid comes.’”

Once the baby arrived, it was a different story. “She didn’t see him for another five years. And he took $27,000 from her; money from a tour that she was then supposed to pay bills with. I think she was a little bit naïve towards Larry and what he would do, and got taken advantage of. But on top of that, he left her with a kid.”

The baby’s precarious health made a bad situation worse. “Daniel was born with medical problems, and Jennifer was desperately trying to get ahold of Larry, because her doctors needed to know about him, they needed to know blood type, medical history, stuff like that. Larry wouldn’t return her calls.”

As the film commenced production, Di Sabatino was aware of the story, and that the boy lived in Australia, but had little more to go on. It appeared to be a dead end, until, during an Australian tour, Randy Stonehill was approached by Daniel himself.

“The kid came up to Randy and started talking to him. I got this postcard the next week,” Di Sabatino recalls, “they said ‘We found the kid, and guess what? He knew your name, and he knew that you were doing the documentary, and he wants to be in it.’ We didn’t know where he was, but he came and found us, because he had heard about this documentary.”

Describing their initial meeting, Stonehill breaks into tears, astonished that Norman could have abandoned both mother and child.

Photos of Larry kissing Jennifer’s pregnant belly, Larry and Daniel together – including a trip to Disneyland – as well as letters between the two illustrate the tenuous relationship between father and son.

Daniel was on hand when Fallen Angel was featured at the Cinequest Film Festival. “A bunch of people who knew Larry came with questions. After meeting Daniel, and after spending time with him – and of course I didn’t have this perspective, because I never spent a lot of time with Larry – they were saying ‘My God, that’s his son; he looks like him, he acts like him, he’s just got so many characteristics of his.’ And this story just fits.

“There’s emails. There’s also the fact that when Daniel came to visit, he admitted it to one of the guys in People. Larry said: ‘Let’s go visit my son.’ But the Norman family, of course, says ‘You don’t have concrete proof.’ They live in a fairyland.”

To date, the Norman family has refused to allow a DNA test that would confirm Daniel is Larry’s son.

“The irony is, if you go on their site, they’re still taking money for all the kids that Larry sponsored. To do that in the face of this kid that has come forth, which nobody argues now that he’s Larry’s son.

“To me, I’ll never get over that one. How do you do that? How do you get up night after night after night? Look; rock stars having kids out of wedlock, that’s no big deal. But you’re spreading this stuff on stage to these people, knowing full well. That’s amazing to me.”

In the film, Robinson forgives his father, and wishes for God’s blessings on each of them.

Some have question Norman’s mental health, positing that he was a sociopath. “I’m not qualified to say that,” admits Di Sabatino, “I’m not qualified to give that diagnosis. It certainly fits the profile. I think something happened to him when he was very young, something horribly tragic.

“That‘s one of the things that he shared with Lonnie. [Frisbee was sexually abused as a child]; that something tragic kind of shaped them, and not for the better. I think he had a hard time trusting people, so if anybody got too close,” Norman would destroy the relationship. “It was a survival technique, it was like; ‘this person is going to hurt me.’ So he triggered off that.”

Di Sabatino refuses to accept mental illness as an overriding excuse. “People will say, ‘He couldn’t help it.’ But I don’t buy it. Personal responsibility has to clearly be upon the person. This guy was too brilliant. He was too calculating, and he was too in the moment to not know exactly what he was doing.”

A more charitable diagnosis would be bi-polar disorder. “He claimed to be. Mental illness ran in his family. When they first got married, he told [first wife] Pamela that everybody in his family ended up in asylums, but not him, because he had Jesus.”

Such thinking was typical of the era. “The 1960s; there’s a naiveté to that time. But I think there was some of that. In my own parsing – and I’m not the adjudicator here for Larry’s life – but anything that takes away from personal responsibility, I just don’t buy in this instance. But that might have been true, all of those things might have been true. Daniel has some bi-polar tendencies, but I think he’s a little more aware and on top of them. But he suffers from that stuff.”

Norman’s failure to deliver on the promise of his early work is a mystery no one quite understands. “I’ve asked these people, and they don’t know. He had the meltdown in 1980, and I don’t know if that affected him, or it happened before and he knew that he was losing his touch.

“Chris Willman from Entertainment Weekly had a great analogy; it’s like Orson Welles. He had these flashes of brilliance. You can put on Only Visiting This Planet today, and it’s still fresh and relevant. It moves people because it’s so well put together. But twenty, thirty years down the road, you’re left thinking there must have been something else besides. All the excuses about why he’s not making something along the lines of Citizen Kane – or why Larry’s not doing something close to Only Visiting This Planet – something else is going on.”

For the last seventeen years of his life, Norman claimed to be beleaguered by ongoing, heart-related medical emergencies and desperately in need of funds for surgery.

For the last seventeen years of his life, Norman claimed to be beleaguered by ongoing, heart-related medical emergencies and desperately in need of funds for surgery.

A fiancé from the time tells of becoming more and more uncomfortable with the notion that he was simply putting on an act. “This woman was a part of his life, [and] that’s what she came to realize; that he was defrauding these people.”

Di Sabatino witnessed a 1992 show where a visibly frail Norman spoke of his need for expensive medical care, without which he would surely die. An audience member offered a spontaneous prayer for money, and a bucket was passed. “In the second half, he’s doing leg kicks! Where’s the guy that was dying? And he’s doing this night after night after night. And you go ‘What in the world is going on here? Am I being conned? And how am I the only one that’s being bothered by this? I’m sitting in the audience, and it’s not bothering anybody. You know, ‘Good old Larry.’ What?!”

At the time, it was more of a gut feeling. “I didn’t know the extent of this stuff. I had no idea what I was unraveling when I started this. People tried to tell me, of course, but you can’t really understand it until you go down that rabbit hole. And as I started to unravel this, it just got worse and worse and worse, and I realized, this is a fraud, this is a sham. What’s he doing?”

The original edit of Frisbee had used Norman’s music, and received a hearty endorsement from the composer. “You know, he was into it. He thought that it was a good movie, and said he wanted to help. Naively, I thought he was being genuine.”

They discussed putting together a CD soundtrack of the film. “Then he releases the soundtrack – which we were talking about doing together – and just goes ahead and does what he wants. When I objected to it, he started with the stories. He set me up like he set up everyone else, and I found that this was a pattern in his life; he brought people close, got them in a position where they needed him, and then he sunk his talons in ‘em, and he turned the knife, over and over again.”

At the 11th hour, Norman pulled his music from the Frisbee film, necessitating an entirely new soundtrack.

“I had already planned to do this film on him, and I had talked to him prior to that. But then my curiosity got to me, and I needed to do it.

“But I counted the cost; I knew that taking on somebody like this was going to be like going

down into Hades and wrestling with the powers that be. I mean, this guy was good at what he did. And so you knew that your reputation was going to be questioned – I had watched him do it to other people through the years. I knew that would come back my way, and it did. That’s when he started with the story of how I was doing it as a vendetta, and stuff like that.”

Once the film was completed, an attempt was made to block public showings. “We had to stop because of a challenge on copyright issues.” The Norman family threatened to sue, claiming 84 copyright violations in the movie. “We were using Larry’s music, and we asked to court go give us clearance on those materials using a law called ‘fair use.’ That challenge is over now. It’s been cleared, so we’re good to go again.”

In many ways, Fallen Angel is simply following Larry’s own example. In the preface to the second edition of The Jesus People Movement (2004), Di Sabatino wrote: “…Norman’s willingness to engage uncomfortable truths within his songs brought a much needed challenge to the status quo…where so many pandered to what the audience wished to hear or the more tried and true means of expression, Larry Norman defied social convention and allowed the Spirit to flow through and create a legacy that will outlast his lifetime. In an age where too many voices are grumbling and arguing what is wrong with this and that, Larry Norman taught me that one’s greatest protest is laid down in an act of creation.”

In many ways, Fallen Angel is simply following Larry’s own example. In the preface to the second edition of The Jesus People Movement (2004), Di Sabatino wrote: “…Norman’s willingness to engage uncomfortable truths within his songs brought a much needed challenge to the status quo…where so many pandered to what the audience wished to hear or the more tried and true means of expression, Larry Norman defied social convention and allowed the Spirit to flow through and create a legacy that will outlast his lifetime. In an age where too many voices are grumbling and arguing what is wrong with this and that, Larry Norman taught me that one’s greatest protest is laid down in an act of creation.”

Outside of the small but vocal minority, support has overwhelming positive. Especially from those who lived the story. Di Sabatino has become friends with the Solid Rock family. “I’ve been invited to hang out with these guys that were my heroes. They welcome me as one of their own. They had a wake in Nashville for Larry, because none of these guys wanted to go to his funeral, and I was two feet away from Tom Howard and Randy Stonehill as they played ‘Pardon Me.’ I’m telling you, for a guy that grew up listening to these guy’s music, I’m like, ‘What am I doing here,’ and there I was, and they were all gathered there to watch the movie.”

In the end, everyone has forgiven Norman. The fact he really did hurt these people –deeply – and never admitted, nor asked to be forgiven – makes their collective action all the more remarkable. “And you feel sorry for him. See, that’s the thing,” Di Sabatino argues. “They still forgave him, and that’s a good thing. People’s lives were positively impacted. And the music resonates – the music goes on.”

A DVD of Fallen Angel is available for purchase through the film’s official site.

© John Cody 2009