It’s a story of extreme excess, dodgy deals, profound tragedy and – eventually – redemption. A story so remarkable, it almost reads like a cliché-ridden TV movie of the week, or a cry-in-my-beer country song. Unbelievably, it’s all true.

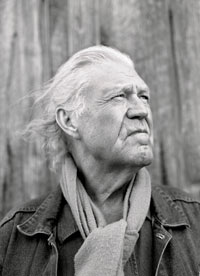

Billy Joe Shaver was arguably the most promising of all the singer-songwriters to come out of Austin and Nashville in the early 1970s. More than anyone else, he created – in fact, lived – the Outlaw persona, mixing traditional country music with rock star rebellion.

Billy Joe Shaver was arguably the most promising of all the singer-songwriters to come out of Austin and Nashville in the early 1970s. More than anyone else, he created – in fact, lived – the Outlaw persona, mixing traditional country music with rock star rebellion.

He drugged, drank, bar-brawled, and consistently sabotaged any chance for success. Over the years his body has withstood the loss of three fingers, a broken back, quadruple-bypass heart surgery, a steel plate in his neck and 136 stitches to his head.

All the while, he was writing some of the most insightful, heart-breaking love songs ever heard.

The last few years have brought a spate of Shaver-related releases. In addition to a number of recent Cds, The Portrait of Billy Joe was a well-received film by Luciana Pedraz, his autobiography; Honky Tonk Hero (University of Texas Press) was published, and he was profiled by the venerable television newsmagazine 60 Minutes.

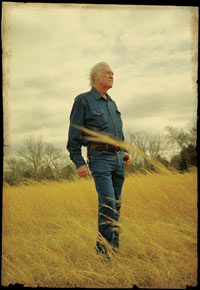

Add his appointment as Texas State Musician by the Texas Commission of the Arts, and it’s clear he’s finally getting the respect he’s always deserved.

Speaking with Shaver, it’s clear – like the title of one of his albums – he’s the real deal. He’s honest, humble, but most of all, human – and, like every one of us, full of contradictions.

Billy Joe was born in Corsicana, Texas, on August 16, 1939. His father, Buddy – a mix of Blackfoot Indian and German – was a bootlegger; a moonshine runner, with a hot temper and a reputation for fighting. His mother Victory was of Cherokee and Irish descent, and just as stubborn.

The couple already had a two-year old daughter when Victory became pregnant for the second time. Buddy was convinced his wife was cheating on him, and after administering a brutal beating, left her for dead in a nearby water tank.

When her body was discovered the next day, a faint heartbeat was detected, and she was eventually nursed back to health. Filled with bitterness, she swore that if the baby was a boy, she was leaving. A month after Billy Joe was born, she did just that, heading off to Waco to work the Honky Tonks.

Aunts and uncles agreed to look after his sister, but wanted nothing to do with Billy Joe. They had already decided to send him off to an orphanage when his widowed Grandmother intervened, taking it upon herself to raise him on her own.

It wasn’t easy. For the first few years, health was an ongoing concern; “Measles, diphtheria, small pox, I had everything,” he recalls, “one right after another. Just almost dying all the time.”

Grandma prayed daily, and dutifully sent him off to Sunday school each week, where the children were awarded gold stars for memorizing scripture. Curiously, the stars were placed on their foreheads. On good days, Billy Joe would return home with a row proudly displayed across his forehead.

Grandma prayed daily, and dutifully sent him off to Sunday school each week, where the children were awarded gold stars for memorizing scripture. Curiously, the stars were placed on their foreheads. On good days, Billy Joe would return home with a row proudly displayed across his forehead.

In the 8th grade, an English teacher insisted he had a gift for poetry, and entered him in a creative writing competition. She was the first to recognize his potential, and her faith made a lasting impression. “I kept that in my heart; it blossomed like a mustard seed.” He quit school that same year, but never forgot his teacher.

Meanwhile, a community of African Americans had settled in the area to pick cotton, and he began hanging out, playing guitar, learning blues songs and getting a musical education.

In the late 40s Shaver got to see a then-unknown Hank Williams sing on a show headlined by Homer & Jethro and the Light Crust Doughboys. “He hadn’t hit yet. I didn’t know him at all. I hadn’t never really heard of him – none of the people had. This was way before he even got cooking. It was at the Miracle Bread Company, and people were bootlegging and smoking all over the place, so when he come out, nobody paid no attention to him.”

Except for Billy Joe, who was mesmerized. Hank noticed, and sang right to him. He can’t recall the song he sang that night. “Man, I’ve tried and tried to remember that song, but I swear I can’t remember what it was. I don’t think it was one of his songs – I think it was an old song. He might have just decided to do something real old-timey. But [whatever it was], it didn’t work, ‘cause everybody went to doing their bootlegging and their smoking and their talking, and wasn’t nobody paying attention to him but me.”

Billy Joe had snuck into the show, which was pretty much the only way he got to see music back then. “I didn’t get to go nowhere. We were real poor.” When money was especially tight, he would sing for credit towards food at the local general store. “My Grandmother raised me on her old age pension, so you can imagine.”

Billy Joe had snuck into the show, which was pretty much the only way he got to see music back then. “I didn’t get to go nowhere. We were real poor.” When money was especially tight, he would sing for credit towards food at the local general store. “My Grandmother raised me on her old age pension, so you can imagine.”

Despite the hardships, he treasures the years they spent together, and is adamant everything would have turned out different had she not been there for him; “I just wouldn’t be here. I’d be dead, I’m sure.”

His Grandmother passed away when Billy Joe was twelve, and, with no other options, he was sent to live with his mother and her new husband in Waco. It didn’t go well.

“We didn’t get along too good, my stepfather and I, and I stayed gone most of the time. I’d hit the rails, or the highway. They didn’t care much whether I was gone or not, because they had less trouble when I wasn’t there. I’d hitchhike all the way to Arizona. Shoot, I’d hit the road. Back then you could hitchhike anywhere you wanted to go. It was pretty easy, and there was some nice people out there. I gathered oranges, worked service stations and stuff…I done everything in the world you can think of, until finally, when I turned 17 – the day I turned 17 – I joined the Navy, because they’d let you join on the day you turned 17.”

That was also the day he crossed paths with a second music icon: Elvis Presley. “He was going out to L.A. on a plane in front of me. There was two planes, and I was supposed to go on that plane, but I wound up going out on the next one. They trained some of us out there, and they put us on planes. There were four of us on each, and he went on the one ahead of me.

“But it was my birthday, and it meant a lot to meet him on my birthday. I thought the world of him, I really did. The boys on the plane said he was just the greatest guy in the world, gave away everything that he had to the stewardesses and stuff, and then gave rings away and stuff. Just a good old boy.”

Years later, Elvis would record one of Shaver’s songs, but at this point just getting to meet the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll was thrill enough.

After a few years of active duty – and in spite of arrests, drunken brawls and going AWOL – Shaver received an honorable discharge in 1961.

Returning to Waco, he met Brenda Tindell, the woman he describes as the love of his life. She was 17 and still in high school when they met, and within a couple of weeks, pregnant with his baby. They married right after graduation, and their son, Eddy, was born in 1962. The marriage was short-lived, but the tempestuous relationship would continue over the next four decades.

To support his new family, Billy Joe took a job at a local sawmill. Most weekends he traveled, working as a bronco buster on the rodeo circuit. In a reversal of most musicians’ attitudes, he figured he could always fall back on music if things got tough.

A sawmill accident resulting in the loss of three fingers on his right hand provided incentive to make the change. He got serious about his songwriting, and after a few tentative trips, moved to Nashville in 1966, where Bobby Bare hired him to write for his fledgling publishing company. Best known for 1963 pop hit ‘Detroit City,’ Bare was in the middle of a lengthy hot streak which would eventually net him 70 charting country hits between 1962–1986. Bare would go on to record many of Shaver’s songs.

By the time he got to Nashville, Billy Joe was a world-class drinker. Despite the partying, he never forgot his past, and made it a habit to read the Bible every day. “My father had left before I was born, so God was my father. I was straight with him; that happened before I even started going to Sunday school.”

On occasion, the seemingly disparate worlds would connect. “Bobby and I would get together and we’d have us a few drinks. We’d get kind of goofy and want to write, and doggone if we wouldn’t wind up writing spiritual songs. I’d say; ‘This is just blasphemous,’ and he said ‘No.’ He said; ‘this spirit and that spirit, they’re close in a way, because your – pardon my English, but your ‘give a shitter’ – goes right out the window. Because you don’t care.”

Shaver expounds; “When you’re in God’s arms, you don’t care because you know you’re took care of. And when you’re drunk you don’t care, just ‘cause you don’t care. When you’re in God’s care you feel that same feeling, only better. It’s more…” he laughs, “sober.

“‘Course, it isn’t what goes into your mouth that defiles you; it’s what comes out. But if you drink enough of it, I guarantee you ain’t gonna know what’s coming out. Jesus said that himself. But, you know, it loosens you up, and anything’s apt come out of that mouth, man. You gotta be real careful when you drink. It’s best not to even drink at all.” It would be a few more years before he would take his own advice.

Songs like ‘Jesus Is the Only One That Loves Us’ and ‘Jesus Christ, What a Man’ came out of these sessions. ‘Ride Me Down Easy’ harkened all the way back to his Sunday school lessons, with a lyric about being “a hobo with stars in my crown.” The song was a hit, but he saw little in the way of remuneration. After four years he was still on salary, making $50 a week and sleeping on Bare’s office couch. On lean weeks, he would supplement his income by washing dishes.

Frustrated with his lack of progress, Shaver decided to move back to Texas in 1971. He told Bare, who convinced him to stick around for the night before heading out, as he had an meeting with Kris Kristofferson, and wanted Billy Joe to play him one of his new songs; ‘Christian Solider.’

Kristofferson was the hottest new writer in town, with ‘Me and Bobby McGee,’ ‘For the Good Times’ and others becoming instant classics. Billy Joe played him the song, and a duly impressed Kristofferson declared he was going to record it on his upcoming album. Accustomed to empty promises, Shaver drove back to Texas that same night.

Within a month, Kristofferson’s album had been completed, and ‘Christian Soldier’ was included. Bare had listed himself as co-writer for having added ‘Good’ to the song’s title (consequently entitling him to half the royalties), but that was hardly a surprise.

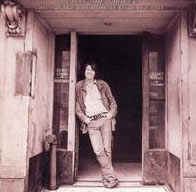

Billy Joe headed back to Nashville. Kristofferson had proclaimed him a major talent, and resolved – despite being broke – to spread the word. “He borrowed money and did my first album…he’d already hit with that album [1970’s Kristofferson – reissued in 1971 as Me and Bobby McGee], but it takes about a year before you make any money, so he borrowed the money.”

The sessions went well, but industry politics would keep the record on the shelf for the next couple of years. “Kristofferson’s label (Monument) bought the album once it was finished, and then sat on it for a year.” Shaver figures they saw him as potential competition for their biggest act, and held up it’s release.

While his album sat in limbo, others were discovering Shaver’s songs. Intelligent, insightful, and often autobiographical (‘Georgia On a Fast Train,’ for instance, lists all the significant events in his life up to that point), ironically, they translated extremely well for other artists.

Most significantly, Waylon Jennings recorded Honky Tonk Heroes, with all but one song written by Billy Joe. Initially, Jennings’ label was unhappy with the idea of releasing a collection of songs by an unknown writer, but the album proved a resounding success, racking up impressive sales and becoming one of the bedrocks of the fledgling Outlaw movement.

Most significantly, Waylon Jennings recorded Honky Tonk Heroes, with all but one song written by Billy Joe. Initially, Jennings’ label was unhappy with the idea of releasing a collection of songs by an unknown writer, but the album proved a resounding success, racking up impressive sales and becoming one of the bedrocks of the fledgling Outlaw movement.

With Waylon’s album a hit, Monument decided to release Shaver’s debut in 1973. Old Five and Dimers Like Me was a perfect showcase. Like Kristofferson, others would have more success covering the songs, but any lack of vocal chops was more than made up for in authenticity.

The opener, ‘Black Rose,’ includes a classic Shaver couplet; “The Devil made me do it the first time/The second time I done it on my own.”

Reviews were overwhelmingly positive, but the timing couldn’t have been worse; the label went out of business soon after the album was released.

It wouldn’t be the last time his recording career was hampered: a subsequent stint on MGM lasted long enough for one single before a headstrong Shaver was dropped due to friction with the label head. His second and third albums followed on Capricorn, which folded soon after.

Perhaps the biggest blunder was his declining to participate on Wanted! The Outlaws, a 1976 compilation featuring Jennings, Willie Nelson, and Jessi Colter. Billy Joe was asked to take part, but Brenda (they had remarried) advised against it, arguing he would be forever associated with the movement. The disc became the first-ever country album to sell a million copies.

In spite of the stop-start nature of his own career, Shaver’s talents were held in high regard by his peers. Johnny Cash called him his favorite songwriter, and Willie Nelson claimed he might well be the best alive. Along with Waylon, Willie and Johnny, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan and the Allman Brothers were among the scores of acts adding his songs to their catalogues.

There’s no magic formula. “I’ve just written songs about me – the good and the bad, the funny and the sad. All I know is that I learned how to turn loose when I first started talking. I learned how to let it go. And that’s a big part of it right there; just learning how to let it go. Get down with it.”

Country pioneers like Hank Williams, Roy Acuff and Redd Stewart made an indelible impression, but so did a few modern writers, especially Bob Dylan, who, Shaver claims, taught him that songwriters have a moral obligation to expose the truth. “I’m not no minister, but I am into the truth. And if you’ll stay truthful, I’ve noticed in songwriting, you’ll always be different. ‘Cause God made us all different, so we all got that in common. If you’ll just stay truthful, you’ll be different.”

Faith has been a frequent theme in his writing from the start. On his recording debut – a one-off single for Mercury in 1970 – he sang of getting back to a simpler time; ‘With those hallelujahs ringin’ everybody’s shouting singing/Give me that old time religion Jesus loves me this I know…’ The single flopped, and he was dropped from the label.

Shaver figures his subject matter was as much a hindrance career-wise as his wild ways. “It was offensive to most all of them – everybody in Nashville at that time. That’s how it was. And me, I came in there with Jesus in my heart, all the way, even though I hadn’t even been born again, yet. But I came in there with the knowledge that he was number one, and I just didn’t take nothin’ off of nobody, ‘cause I was a respecter of no persons – and a lot of that is the reason why I didn’t get no further than I did right away.”

On occasion, the opposite proved to be true; his gospel-leaning material was well-received in some quarters, as he’s quick to point out. “The first song I actually got nominated for a Grammy was ‘Jesus Christ, What a Man’ [in 1971]. The Oak Ridge Boys did it when they were still a gospel group. I got nominated with that, and it didn’t happen. I think it was ‘Put Your Hand In the Hand’ beat it out, and I can see why.” Typically transparent, he stops to reconsider; “Well, not exactly…I don’t know…it was a pretty good song.”

By the late seventies, Shaver’s life was out of control. Rolling Stone – who had called Old Five and Dimers Like Me one of the finest of the year – noted; “There seemed to be no way he could blow it – but blow it he did.”

He places the blame squarely on his own shoulders. “I smoked, drank, doped, did everything. There wasn’t anything happening that I didn’t do.” He was back with Brenda, but that didn’t stop either of them from stepping out on the other.

After a night of carousing, he arrived home to discover a glowing figure sitting on the edge of his bed. Due to his level of intoxication, he initially thought it was a hallucination. The figure kept shaking it’s head, repeating “How Long? How long are you going to keep doing this?”

Terrified, and unsure if it was an angel or demon, he took off – driving to a local cliff where he planned on jumping to his death. When he got to the top, he discovered an altar.

Shaver still intended to jump, but somehow – he believes it was divine intervention – found himself turned around, barefoot, and on his knees, praying for forgiveness.

Later, while walking back down the hill, he began humming a tune he didn’t recognize. By the time he reached his truck, half of one of his most popular songs, ‘I’m Just An Old Chunk of Coal,’ was written.

“I was like a little kid after I came down that hill, real vulnerable, and some kind of voice inside of me – not an audible voice – it just said; ‘Get ‘em out of here.’ And sure enough, I had old friends there that would have killed me if I had stayed and kept doing the same thing.

“I took my family and went down to Houston.” It was a tough go for a while. “I went cold turkey on everything. I was in such bad shape I couldn’t hardly put a sentence together. It took me six months, and I dropped down to 150 pounds. All I could keep down was Melba toast and, of all things, A&W Diet Root Beer. I could keep that down, and that was it. I was dwindling off to nothing. My wife and son stuck with me, though.”

His healing is inextricably linked with two songs.

“It’s funny – the night I finished ‘Old Chunk of Coal,’ I went that whole day doing the Melba toast and Root Beer thing. And then, the next night, I wrote another song about Jesus, called ‘I’m in Love’ – and it was like an umbilical cord had finally been broken, and I was free to begin the beginning of forever.

“And that’s when I really became born again; and that’s when I was able to keep food down, and I made my comeback. I came back very slowly. Very slowly – but I made it back.”

Shaver’s new-found sobriety was accomplished without costly rehab or therapy. “As a matter of fact, I didn’t know about rehab. And thank God I didn’t, because I have friends that went into rehab the same time I was doing my Jesus Christ thing, and they’re still going in and out of rehab. And I don’t have to. It’s done. It’s over with.”

‘Old Chunk of Coal’ became the title track of his next album. The lyric has proved inspirational for listeners ever since; “I’m gonna kneel and pray everyday/Lest I should become vain along the way/I’m just an old chunk of coal now, Lord/But I’m gonna be a diamond someday.”

‘Old Chunk of Coal’ became the title track of his next album. The lyric has proved inspirational for listeners ever since; “I’m gonna kneel and pray everyday/Lest I should become vain along the way/I’m just an old chunk of coal now, Lord/But I’m gonna be a diamond someday.”

Not that he had gone soft. ‘Ragged Old Truck’ grumbles about how “…this married-up life I’d been livin’ was tryin’ to choke me to death.” Underscoring the volatile nature of their relationship, the same album’s ‘Fit To Kill and Going Out in Style’ refers to Brenda lovingly as “the queen of the world.”

The couple divorced twice, and Billy Joe says she left him more times than he can count, yet through the good times and the bad, she remained his muse. “Most of my songs were written trying to get back in the house. Or trying to stay alive; one or the other. I guess that’s why I wrote so many good songs.” ‘I Couldn’t Be Me Without You’ is typical. She had moved out, and he called her at four in the morning to read her a poem “She liked that line, and that became the song.”

She also liked Elvis, which he figured might score some points. In addition to the encounter on his 17th birthday, Elvis recorded Shaver’s ‘You Asked Me To,’ and, by a strange coincidence, died on Billy Joe’s birthday.

“Brenda, she used to be so hard to impress, and I asked her about it. I said; ‘What do you think? The King – the King – he died on my birthday.’ And of course, he’s not the King; the King is Jesus Christ. But I said; ‘What do you think about Elvis dying on my birthday, and I met him on my birthday?’ She thought a while and she said ‘Aw, that’s just probably Elvis’ way of saying goodbye.’ Well, thanks a lot, Brenda,” he chuckles. “I couldn’t impress her with anything.”

Not that he disagrees with her assessment; “It’s interesting, but that’s about it. Don’t mean much of nothin,’ really.”

Shaver had been straight for two decades when the toughest test came at the end of the nineties. In the span of a year, he buried his wife, son, mother, and mother-in-law.

Brenda was diagnosed with advanced rectal cancer in 1996, and they married for a third time. Billy Joe cared for her until her death in the summer of 1999.

He claims he was only ever capable of loving one person, and the years since Brenda’s passing bear that out. Shaver has subsequently married – and divorced – twice. “Same woman [both times], and we split up. It was a lot of sympathy and stuff involved in there, and it didn’t turn out to be. You know, I don’t guess I’ll ever be able to love anybody like I did that first one.”

Eddy played guitar with Dwight Yoakum, Guy Clark and Willie Nelson, but he was best known for his work with his dad. From the time he was thirteen years old, the two played together.

Billy Joe’s estimation of his own fathering skills is typically frank; “I didn’t set a very good example.”

Growing up – both at home and on the road – Eddy was surrounded by drugs. At the time, Billy Joe rationalized his behavior as a way of showing his son what not to do. Once he sobered up, he tried to right the wrongs, but by then Eddy was developing his own problems with drugs.

Growing up – both at home and on the road – Eddy was surrounded by drugs. At the time, Billy Joe rationalized his behavior as a way of showing his son what not to do. Once he sobered up, he tried to right the wrongs, but by then Eddy was developing his own problems with drugs.

Both were deeply shaken by Brenda’s death. Shortly after her passing, they attended church together. Once again, Eddy was trying to get straight, and they approached the altar for prayer. The preacher asked Billy Joe what meant the most to him in this world, and he said his son. Responding to the same question, Eddie said it was his father. The preacher inquired if they would give the other up to God if God asked, and both replied in the affirmative.

A few weeks later, Eddie overdosed from heroin. Initially, Billy Joe was out for blood; “I wanted revenge. I wanted to kill every drug dealer on earth.” He prayed constantly, and eventually got an answer; “‘Vengence is mine saith the Lord. Leave it alone, I’ll take care of it.’” He stopped fantasizing about payback, and later learned that Eddie’s dealer had been killed.

For a long time, he blamed himself for his son’s death. When the anger subsided, he realized he had to forgive a lot of people – including himself. “I did. I sure did have to forgive myself. I have to do that pretty much – a lot. But he’ll forgive us seven times seventy, and that’s a bunch; but I don’t try to push it anymore. I used to, but [not anymore].”

The subject of forgiveness comes up frequently with Shaver. He figures he’s received far more than he deserves, and tries to make amends. “You know, I try every day, man. I’m really trying to be like Jesus. God, it’s wearing me out. But I’m trying to be like him, and I don’t know how in the world he did it. I can’t imagine. In this world? I just don’t know.

“The only thing – the thing that helps me a lot – is that some of the greatest sinners are saints.”

He brings up Paul, who went from persecuting Christians to leading the church. “And I realize now that it’s not impossible for a person like myself, that’s been a big, big time sinner to become a good person.”

Towards that end, there are plenty of opportunities. He even forgave Bobby Bare. “Yeah, I got kicked around a little bit with Bob. But you know, all in all I don’t dislike anyone. I love everybody; it’s just the things they do sometimes I don’t like. And I can get over that; ain’t no big deal. It’s all vanity, anyway.

“I just like to write a good song, and I know one of these days I’m not gonna be here, so what in the world am I gonna have to crow about?”

In 2001 Shaver suffered a massive heart attack, and underwent a quadruple heart bypass. It didn’t even phase him. “I’ve had so many near-death experiences, and I felt comfortable with them, because God was with me. You can’t imagine how good it feels to know you’re near death, and know you’re in God’s hands. You feel better than you’ve ever felt in your whole life. I mean, it’s just the doggoned-est feeling.”

Death holds no fear. “I’m ready either way. If something happens to me, I’m ready. It’ll happen whenever God wants it to happen, so I’m not worried about it at all. I guess that’s why I’m so loose and everything, and I enjoy life so much. It’s not that I don’t care; it just doesn’t bother me.”

Death holds no fear. “I’m ready either way. If something happens to me, I’m ready. It’ll happen whenever God wants it to happen, so I’m not worried about it at all. I guess that’s why I’m so loose and everything, and I enjoy life so much. It’s not that I don’t care; it just doesn’t bother me.”

While his faith defines him, he has little interest in theological debate, especially when it comes to denominations. “Just any church I go to is fine. There’s a lot of people there for different reasons, but I’ll guarantee you, the underlying reason is that they want to be close to believers, the body of believers. Anyway they can get in there is good. I believe in the church, I really do. And every chance I can [I go] – but it seems like I’m always playing somewhere.”

Since he can’t always get to church, he brings church to his shows. “I’m actually witnessing all the way through. Every show I do, I witness. So I’m just as much at church. I always end with two or three [gospel songs]; ‘You Can’t Beat Jesus Christ,’ or ‘Jesus Christ Is Still the King,’ or things like that. I always end my shows like that.

“Most people – well, pretty much every one of them – go away thinking they’ve been to church; they tell me that. Everyone knows I’m a Christian, and everybody there’s a Christian. Well,” he corrects himself, “if they’re not, they’re gonna be pretty soon. I have bikers that come back there and just cry, and pray with me and stuff. I pray with somebody every show; there’s always somebody that needs prayin’ with.”

Sharing one’s faith onstage might not be a good career move, but he’s convinced it’s what he should be doing. “I think somehow or another, that God has some kind of special purpose for all of us, and that possibly was mine; so that I could go into them Honky Tonks and just be myself, and deal with all of that stuff, because you can’t go in there being goody-goody two-shoes…

“It’s just, being born again is kinda dangerous, really. You feel like a little kid, and you want to share everything with everybody, and you’re jumping up and down, happy and all about it and all that stuff. But you still make the same mistakes.”

Some mistakes, he admits, are more serious than others. “Here I am one to talk, but you know, it’s just, ah, things happen. You get your toes stepped on when you’re blessed, it kind of goes out the window. You know; somebody stomps you on the foot or something, you’re thinking about being blessed don’t come up.”

Shaver – who once sang about being ‘a pistol-packin’ poppa with a million dollar smile’ – made news last year after he was charged with shooting a stranger in the parking lot of a bar in Texas. The victim – drunk, aggressive, and armed with a knife – was shot in the cheek, but not seriously harmed.

“Well, he threatened me – he threatened me. I mean, bodily, and with a deadly weapon, and then we went outside. I went outside first, and when he came out, it was either him or me. That’s all I can say about it. And that’s probably too much.” He reconsiders. “No, no. Anything I say is fine, it’s just; I have to watch it. As much as I can say is, it was either him or me. And that’s all I knew.”

Some reports were particularly hostile towards Shaver, but he’s not overly concerned. “That’s okay. You know, the press never does do anything exactly right. Especially when they’re feeding, like sharks… They’re just doing their job. I understand – I understand that.”

For Shaver aficionados, these are good times. So far this decade, between Cds and DVDs, there have been over a dozen releases. The last year alone has seen three new discs; Greatest Hits (Compadre), Storyteller: Live at the Bluebird (Sugar Hill), and Everybody’s Brother (Compadre).

Storyteller captures an intimate performance from 1992. He’s relaxed, in great voice, and the songs – interspersed with stories and anecdotes – are especially poignant. The stripped-down accompaniment – Billy Joe and Eddy on acoustic guitars along with a bassist – works well, but what really makes this memorable is what was happening behind the scenes. Brenda – divorced from Billy a second time – was in the audience that night, and it’s clear he’s singing for his family; the rest of the audience was just lucky to be there.

Storyteller captures an intimate performance from 1992. He’s relaxed, in great voice, and the songs – interspersed with stories and anecdotes – are especially poignant. The stripped-down accompaniment – Billy Joe and Eddy on acoustic guitars along with a bassist – works well, but what really makes this memorable is what was happening behind the scenes. Brenda – divorced from Billy a second time – was in the audience that night, and it’s clear he’s singing for his family; the rest of the audience was just lucky to be there.

Owing to licensing restrictions, many of the 18 selections included on Greatest Hits are not the original versions. Considering the state of his discography – a myriad labels, some albums never appearing on CD – it’s the best one could expect, and an excellent one-stop introduction. All of the important songs are here, and the performances – a few unique to this disc – are first-rate.

Owing to licensing restrictions, many of the 18 selections included on Greatest Hits are not the original versions. Considering the state of his discography – a myriad labels, some albums never appearing on CD – it’s the best one could expect, and an excellent one-stop introduction. All of the important songs are here, and the performances – a few unique to this disc – are first-rate.

Everybody’s Brother (Compadre) has been described as ‘Honky Tonk Gospel,’ a term Shaver says suits him just fine. It’s his second gospel effort (1998’s Victory came first), but every one of his albums has included at least a few nods to the genre; “You know, I can’t get it out of me. It just keeps on coming, and it’s in there to stay, there’s no doubt about it.”

The disc is nominated for a Grammy – his fifth – in the Best Southern, Country or Bluegrass Gospel category.

The disc is nominated for a Grammy – his fifth – in the Best Southern, Country or Bluegrass Gospel category.

John Anderson is along for the opener, ‘Get Thee Behind Me Satan,’ a fire-and-brimstone style sermonette that gives Old Scratch fair warning. Johnny Cash – who claimed to have sang ‘Old Chunk of Coal’ to himself every morning when he was in rehab – appears (along with a 15-year old Eddy Shaver) courtesy of a late 1970s duet of ‘You Just Can’t Beat Jesus Christ.’

A few more guests show up – including Kris Kristofferson, Marty Stuart and Tanya Tucker – but Billy Joe remains front and center no matter who he’s singing with.

One song almost didn’t make it onto the disc. The label suggested dropping ‘If You Don’t Love Jesus,’ fearing the chorus; ‘If you don’t love Jesus, go to hell’ could be considered confrontational. Not surprisingly, he refused, arguing that if the song is harsh, it’s simply because sometimes, truth is harsh; “He’s coming back…in a different kind of way. He’s coming back, but he’s not coming back as a guy that’s gonna take any slapping around. It’s a double-edged sword that we’re dealing with now, and people should be cool about it, because if you don’t believe, man, I feel sorry for you.

“I didn’t catch on to Jesus at first. It took me until I was a grown man, before I realized the power and strength of the everlasting love of the Lord Jesus Christ. I just had no idea. I wish I’d had known back then, but I didn’t.”

Almost seventy years on, Shaver believes God designated a specific purpose for him even before he was even born. “I think God allowed me to live. He wanted me to tell my story. He saved me, and I’ll always be grateful. I know who saved me; I know who saved me, and I always will know. And I believe that’s why God loves me so much; ‘cause I love him so much.”

© John Cody 2008

Update:

Country singer Shaver acquitted in Texas shooting

04/10/2010

Associated Press

It took a McLennan County jury just two hours Friday to acquit Texas country singer-songwriter Billy Joe Shaver of aggravated assault in the 2007 shooting of another man in a bar parking lot.

An unlawful carrying charge remains pending. Judge Matt Johnson set a $7,500 bond on that charge and told Shaver he was free to go.

Earlier Friday, Shaver testified that he acted in self-defense when he shot Billy Coker in the face near Waco on March 31, 2007. But prosecutors maintained that no other witnesses described Coker as “violent or mean.”

During cross-examination, prosecutor Beth Toben asked Shaver if he was jealous that Coker had been talking with Shaver’s ex-wife, Wanda Shaver, in the bar.

“I get more women than a passenger train can haul,” the defendant replied. “I’m not jealous.”

He said under questioning by his own attorneys that he felt threatened by a knife Coker displayed and with which he stirred his drink and Shaver’s before tapping him on the shirt with it. Under cross-examination, Shaver said Coker eventually called him out to the parking lot at Papa Joe’s Texas Saloon in Lorena and that Coker’s knife kept him from taking his ex-wife and leaving. “All I was paying attention to was that knife and Wanda,” he said.

And he testified he wouldn’t leave his ex-wife at the bar alone. “If I were chicken (expletive) I would have left,” he said, “but I’m not.”

Coker had told authorities that Shaver told him, “Where do you want it?” before shooting him in the cheek. Friday, however, Shaver testified, “I actually asked him, ‘Why do you want to do this?’ For one reason or another, someone turned it into, ‘Where do you want it?'”

After the shooting, he said he called friend and fellow Texas singer-songwriter Willie Nelson and asked for his recommendation of an attorney. Then, Shaver said, he left town out of fear of Coker and his family.

In closing arguments, Dick DeGuerin, Shaver’s lead attorney, told jurors that his client acted out of fear.

But prosecutors challenged that assertion. Toben told jurors that no other witnesses described Coker as “violent or mean.”

Shaver, who lives in Waco, rose to country music stardom in the 1970s. Shaver recorded more than 20 albums and wrote “Georgia on a Fast Train” and “I’m Just an Old Chunk of Coal (But I’m Gonna Be a Diamond Someday).”

His heartfelt lyrics helped launch country’s outlaw movement, which defined the careers of singers like Nelson and the late Waylon Jennings and returned country to its roots.