Alice Cooper has described himself as a prodigal son who “couldn’t get further away from the church,” and a “posterboy for sin.” Today, he studies the Bible on a daily basis.

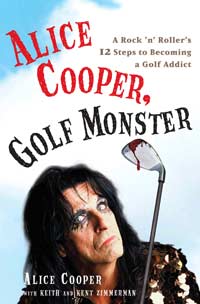

That’s one of the notable facts he shares in Alice Cooper, Golf Monster (Crown), his combination autobiography and golfing manual.

Cooper’s music was always confrontational, and the stage show – which incorporated boa constrictors, electric chairs and outrageous shock tactics – attracted press like a magnet.

The Alice Cooper Group first came together in Phoenix, in 1965. Dubbing themselves the Earwigs, they had mimed to Beatles songs as part of a school talent contest, and – taken with the response – decided to get serious. They changed their name to the Spiders and recorded a single that went all the way to number one in their hometown the following year.

If the tracks included on the box set The Life and Times of Alice Cooper are any indication, they were better than average garage rockers.

Anxious to take it to the next level, the band moved to Los Angeles in 1968, and were soon indulging in everything the city had to offer, from acid to the groupie culture. Alice – a budding track star – was a neophyte; “Personally, I was never much a druggie. I barely even touched alcohol at the time. Still, everything changed after that. We were no longer virgins – on any level.”

As the shows became increasingly flamboyant, it became clear a name change was in order. ‘Alice Cooper’ fit the bill; evoking images of a gentle, long-haired female folk artist, it was perfect for confusing audiences. As front man – Vince is his given name, but he legally changed it to Alice in 1975 – he’s always maintained that Alice is a great character to play; in L.A. in the sixties, there were a million Peter Pans, but nobody wanted to be Captain Hook. Adopting an over-the-top stage persona, he managed to grab the audience’s attention no matter who they came to see.

They caught the attention Frank Zappa, leader of the Mothers of Invention, and the city’s master of all things bizarre. He signed the group to his Straight Records label.

After two releases that did next to nothing, the sound toughened up considerably on album number three: 1971’s Love it To Death. By then they had moved to Detroit and were sharing stages with Motor City acts like the Stooges and the MC5, whose powerhouse live shows invigorated the group.

The album contained their first hit; ‘Eighteen,’ which captured teen angst perfectly: “I’m a boy and I’m a man/I’m eighteen and I like it.”

Killer followed later the same year, and broke them wide open. Songs like ‘Dead Babies,’ ‘Sick Things’ and ‘I Love the Dead’ (the last two from Billion Dollar Babies) were designed to shock. The former, for instance, attracted controversy, but the message was simply that parents need to look after their kids.

After scoring with singles like ‘Under My Wheels,’ ‘Be My Lover’ and ‘School’s Out,’ they hit their commercial peak in 1973, when the album Billion Dollar Babies went all the way to number one.

A year later, amidst inter-group squabbling, the band broke up. The individual members quickly faded into obscurity, but for Alice, the hits just kept on coming.

His debut solo release, 1975’s Welcome To My Nightmare, boasted the biggest live production yet, and the subsequent tour lasted over a year.

Alice maintains there’s very little qualitative difference between rock ‘n’ roll and high culture. Even Shakespeare; “They’re both art, both showbiz.” Like the Bard, much of Cooper’s live show is satirical; holding a mirror up to a society that’s lost it’s mooring, and hopefully getting the audience to consider what’s really going on.

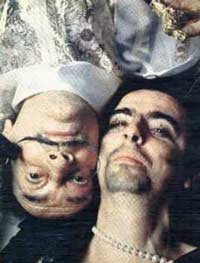

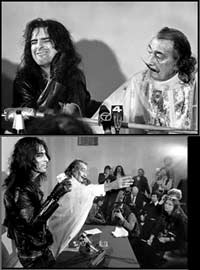

Surrealist painter Salvador Dali loved the whole concept. He’d been a major influence on the group since the beginning, and his stamp of approval was praise of the highest order. In 1973 he created a three dimensional hologram entitled ‘First Cylndric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain.’ Ten years later, Cooper based the cover art for Dada on a section of Dali’s ‘Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire.’

Surrealist painter Salvador Dali loved the whole concept. He’d been a major influence on the group since the beginning, and his stamp of approval was praise of the highest order. In 1973 he created a three dimensional hologram entitled ‘First Cylndric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain.’ Ten years later, Cooper based the cover art for Dada on a section of Dali’s ‘Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire.’

Groucho Marx claimed Alice was the last hope for vaudeville, and he wasn’t alone in his estimation; Alice maintains old school troupers like Jack Benny, George Burns and Bob Hope “saw the bigger picture of my music, more than a lot of fans…I was the guy who did what they used to do. Entertain people. Make them laugh without taking themselves too seriously.”

For all the outrageous antics and over the top productions, what really separates Alice from the rest of the shock-rockers is the high quality of his writing. Bob Dylan described him as an overlooked songwriter, and John Lennon called ‘Elected’ his favourite song. Johnny Rotten auditioned for the Sex Pistols by miming to ‘Eighteen,’ and claims Killer is “the best rock album ever made.” The first record U2’s Bono ever bought was Cooper’s ‘Hello, Hurray.’

For all the outrageous antics and over the top productions, what really separates Alice from the rest of the shock-rockers is the high quality of his writing. Bob Dylan described him as an overlooked songwriter, and John Lennon called ‘Elected’ his favourite song. Johnny Rotten auditioned for the Sex Pistols by miming to ‘Eighteen,’ and claims Killer is “the best rock album ever made.” The first record U2’s Bono ever bought was Cooper’s ‘Hello, Hurray.’

The songs work in a wide range of contexts – the list of artists who have sampled from the Cooper songbook is incredibly diverse, spanning Frank Sinatra, Anthrax, Pat Boone, Sonic Youth and The Muppets.

Surprisingly, many of his biggest hits are ballads, including; ‘I Never Cry,’ ‘You and Me,’ ‘How You Gonna See Me Now’ and ‘Only Women Bleed.’

That last song was particularly popular with female acts; Tina Turner, Carmen McRae, Etta James and Lita Ford all covered the song, and British vocalists Elkie Brooks and Julie Covington both had hits with it in England.

By the mid-70s he had developed an insatiable appetite for liquor. As honorary president of a loose-knit drinking fraternity dubbed the Vampires – charter members included John Lennon, Harry Nilsson, Keith Moon and John Belushi – Cooper would oversee proceedings from their self-styled lair at the Rainbow Bar and Grill on Sunset Boulevard.

“I look back at my drinking club days as another life long ago.” Cooper reflects. “There were great times, but they were also the lost years. But it’s funny, [we] were all extremely productive during that time…we felt immortal and invincible.”

Reprinted from Alice Cooper, Golf Monster: A Rock ‘n’ Roller’s 12 Steps to Becoming a Golf Addict by Alice Cooper. Copyright © 2007. Published by Crown, a division of Random House, Inc.

The hits continued, but by 1977 he was feeling far from invincible. Life on tour was now typified by “drinking non-stop…I was throwing up blood every morning.”

His manager and wife got together and staged an intervention, and “once again, Alice Cooper was ahead of his time.” He checked into a sanitarium – as he points out, long before it became fashionable for celebrities to go to rehab. The Betty Ford Clinic wouldn’t open for another five years.

He came out sober, but gradually returned to drinking.

By 1983 things were out of control. His wife had left, taking their daughter and filing divorce papers. Outside the courtroom, he finally realized the gravity of the situation, telling her; “This is all wrong. I know this is my fault, but this marriage cannot end like this.” The lawyers were sent home, and he returned to rehab for a month.

This time, things were different; “I felt strange, like I had never been an alcoholic, and more important, like I would never be one again…I didn’t feel one single craving for alcohol. It was as if the alcoholic demons were gone. Expelled! I know it sounds preposterous and that people will tell you it’s impossible, but it was as if I had finally proclaimed “That’s it. I’m done. The boy’s had enough.”’

He’s convinced the restoration was supernatural; “I was healed. It’s when I saw the evidence that God did something extraordinary to me. It just disappeared. I was an alcoholic of the highest order, then it was gone.”

His wife insisted they see a marriage counselor before getting back together; one of the counselor’s stipulations was that they attend church together.

He was no stranger to the church.

Cooper’s paternal grandfather was president of the Church of Jesus Christ – a Protestant denomination, despite the Mormon-sounding name – and both of his parents became Christians when he was a youngster. His father gave up drinking, smoking and swearing, but “was still the hippest guy I’d ever met.” The family was living in Los Angeles at the time, and when Dad felt called to work as a missionary with Native Indians in Arizona – he would later become a Pastor – they moved to Phoenix. Alice was eleven years old.

His father was always supportive of the band. While he wouldn’t condone the sex and drugs lifestyle, the records were a-okay. He took a lot of flack from some members of his church; regardless, he always stuck by his son.

Cooper also found support from another musician. As half of Flo & Eddie, Mark Volman was the opening act during the Billion Dollar Babies tour. The two have remained friends ever since.

Like Alice, it took him years to return to the faith he had as a child. For Volman, it was cocaine rather than alcohol that caused problems. Today, he’s an Adjunct Professor at Belmont University in Nashville.

He sees each of their stories as testament to the significance of parental influence. Positive exposure to the church as youngsters – Mark’s grandmother took him to Catholic Mass almost daily – played a significant role in their respective paths home.

Reprinted from Alice Cooper, Golf Monster: A Rock ‘n’ Roller’s 12 Steps to Becoming a Golf Addict by Alice Cooper. Copyright © 2007. Published by Crown, a division of Random House, Inc.

Volman was well aware of Alice’s upbringing, and it came as no surprise to learn his faith had been restored. It all made sense to him, he told me, “knowing [Cooper’s] father had embedded in him a love of life, when I heard of his commitment to Jesus, and the things he’s involved in, in terms of Bible studies.”

After getting straight, Alice took a few years off from recording. He realized – having an addictive personality – that he needed to replace drinking with something more beneficial. Golf was perfect. He’d been playing for years, and was already a skilled player. Pretty soon he was spending eight to ten hours a day on the green, sharpening his game every chance he got.

His love of the sport comes across throughout Golf Monster. He’s not alone; there are scores of like-minded golf fanatics, who gladly traded drugs or alcohol for a golf club.

When he decided to come out publicly as a Christian, he was unsure as to which direction to pursue. His pastor encouraged him to simply continue performing as Alice; his lifestyle was testament enough. He was living a solid life, and that’s what counted.

His longtime manager worried it would all be over when word got out, but Alice argued that he had courted controversy his entire career, and what could be more controversial than proclaiming Christian faith? “Ultimately, becoming a Christian became the most rebellious and risky thing I had ever done. I was now rebelling against the very business that had invented me, and that’s true rebellion. Who’s the biggest rebel to ever live? Jesus Christ.”

His albums since then are informed by his faith, and work well – Alice is the perfect vehicle for offering commentary on a world gone wrong.

In many ways, it’s no different from what he’s always done. There was a clear sense of morality right from the beginning. Songs like ‘The Second Coming’ and ‘Hallowed by My Name’ from Love it To Death reveal a clear understanding of scripture, and he never made it a secret which side he was on.

“I freely show my influences – heaven and hell, good and evil…there was never one time I condoned satanic philosophies, rituals, or behavior…unlike some heavy-metal bands, I completely avoided blatantly satanic material”

In the seventies, he was willing to do whatever it took to shock the audience. Nowadays, he’s imposed boundaries; “And that’s what makes it really fun, that fact that I can be this villain without ever crossing those boundaries, without compromising my morals.”

With a stage show that incorporates simulated beheadings, hangings, and more, he’s a master at manipulating audiences. He can spot a con. Maybe that’s one reason he’s put off by TV preachers who claim to heal people.

“That stuff scares me.” He says. “In fact, most Christians I know are repelled by that kind of behavior.”

© John Cody 2007